Spore

Gene cool.

Will Wright is lying flat out on the floor behind me, his head resting awkwardly on a small pile of books. Pieces of string are tied around his face and pinned to the carpet, with a plastic menagerie of weird alien figurines placed around his head and balanced precariously on the side of his face. I'm trying to play Spore on one of Maxis' laptops, and it's awfully distracting.

The Sims creator has barely moved a muscle for the past quarter of an hour, as an undaunted photographer squats over him, nonchalantly snapping and prodding away. It's a shoot to accompany a profile piece in a British newspaper: the picture is meant to evoke the image of Gulliver in Swift's great satirical novel, tied to the ground by the diminutive Lilliputians.

The implication is, of course, that the freakish inhabitants of Spore's universe collectively have a power far greater than their modest size suggests: and in Wright's case, the power to overthrow their creator and claim a life of their own. It's an appropriate visual metaphor for the game, more so perhaps even than the photographer realises, since if Spore delivers on its promise, it will evolve along a path the development team cannot fully predict, one that is determined by the individual actions of its users, collectively expressed.

If you've been keeping a keen eye on Spore since its unveiling at GDC three-and-a-bit years ago, it's a thrilling, intoxicating prospect. As a mainstream videogame it is unprecedented in its scope and one which, despite its esoteric scientific and social influences, can charm and wow an audience in moments, as I witnessed at Comic-Con in San Diego last month (and you can, too, on Eurogamer TV).

Wright is a brilliant, articulate man and a compelling ambassador for the games industry: the ultimate geek with an unshakeable belief in the transformative potential of interactive entertainment. And, having sold over 100 million copies of a virtual dolls' house, he's earned his stripes.

Until recently, discussion of Spore has been dominated by so much brow-furrowing over its portrayal of complex issues related to subjects as diverse as biology, sociology, astrophysics, technology and environmentalism.

That Spore can form the basis of thoughtful broadsheet articles, where Wright expounds on the collective 'metabrain' and gaming's treatment of the human condition, is an unalloyed good for those eager to see the industry taken more seriously. But with the game due for release in four weeks, there's a rather more pressing question on my mind: is it actually, you know, fun?

To begin to form an answer to that question, I've been whisked away to Maxis HQ in San Francisco to spend a few hours with a practically final build of Spore and speak with Wright and his team as they enter the home stretch of a mammoth seven-year journey. (You can read the full interview with Wright elsewhere, and watch highlights on Eurogamer TV.)

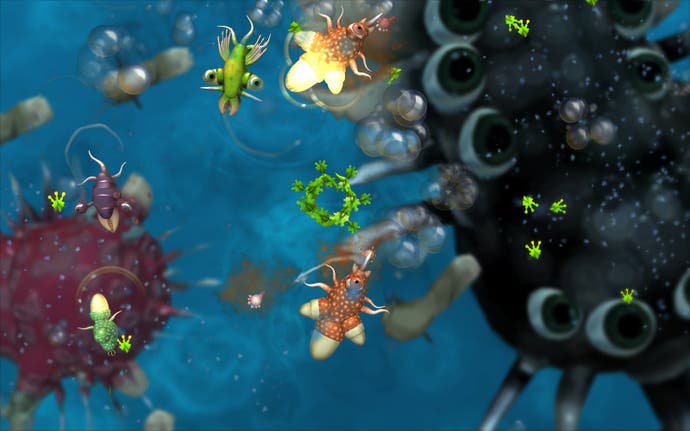

Eurogamer's previews of Spore thus far have come with the caveat that only surface-scratching is possible in a limited time frame. That is unavoidably the case here, too, but with playtime in each of the game's five phases - Cell, Creature, Tribal, Civilisation and Space - the impression is now clearer.

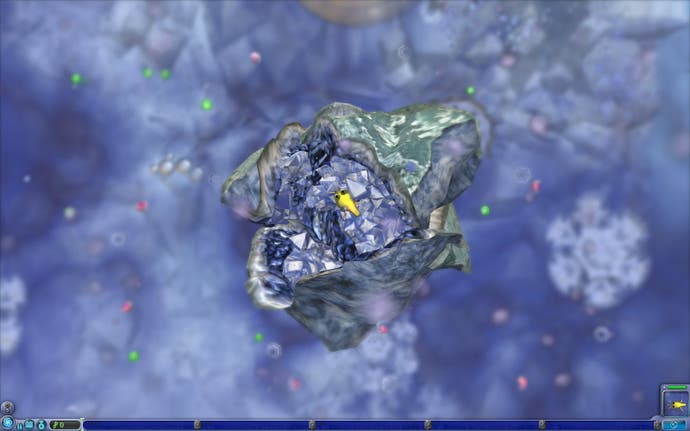

So, let's begin at the beginning. The Cell phase is Spore at its most straightforward - compared by Wright to Pac-Man - and the one I have the lowest expectations for in advance. It's actually magnificent fun. You start off by choosing a star system and planet on which you want to begin your journey (remember that each system will be uniquely populated by user-created species in the final game).

Each Phase has easy, normal and hard difficulties, and in Cell you choose to become either an algae-chomping herbivore, or a plankton-and-other-organism-scoffing carnivore. The choice feels superficial now, but has palpable implications over the course of your species' evolution.

A cute intro sequence highlights Spore's take on the origins of life: the theory of panspermia, life seeded from outer space. The camera follows a rock sweeping past the sun and crashing into the planet's surface, sparking the beginning stages of life in the primordial goo.

Topdown and in 2D, Wright wasn't lying about the Pac-Man link: you have to guide your organism (created in a simplified version of the Creature Creator tool released back in June) through the water, gobbling up food to earn DNA points. You can spend these on new parts to add to your creature to expedite its evolution: to do this you must mate with another organism in a charming sequence reminiscent of Viva Pinata's romance dances, which takes you into the editor where you can add things like spikes, jaws and extra protrusions to help you swim faster.