Fallout 3

Oblivious.

Fallout 3 is such an embarrassment of riches, it's hard to know where to begin. The news is definitely good though, because whichever way you stack it up it qualifies as a landmark game. Like BioShock and Oblivion, unpicking its merits is something of a Gordian knot. But that is, of course, precisely its charm.

The bedrock, as you would hope, is the game's immensely well-realised and beautiful openworld. Arty, varied and epic, it's crafted with attention to detail, housing secrets, lies, hopeless ambition and revenge. The Capital Wasteland has a palpable sense of place, where even the more obscure backwaters hide pleasing diversions, intriguing characters and curious sub-plots.

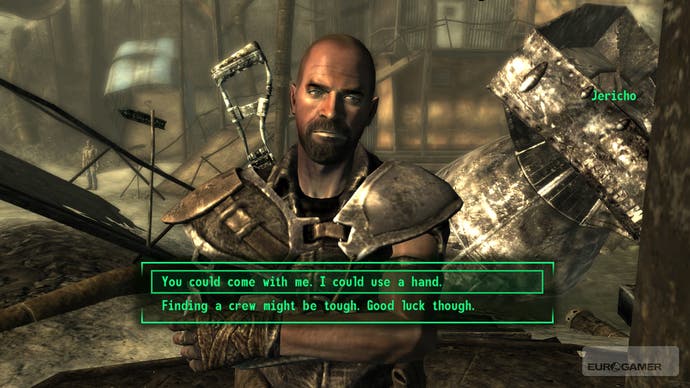

It doesn't seem to matter which angle you take with Fallout 3 though, because there's usually something pleasing to report. It makes the fiddly micromanagement of weapons, apparel and health a relative joy with a slick, intuitive interface. It rewards and encourages progress with a transparent and logical levelling system. It delights with countless improvements to the Oblivion engine, physics and animation. Even the script and voice acting are pretty decent, and there are reams of detailed text logs to discover. At one point, you even stumble across a playable beta version of a fully-fledged text adventure.

Question marks will always linger over how much it can live up to the expectations of diehards, and people will argue about how Bethesda's storytelling stands up to Black Isle's, but this is a new game, from a different developer in a different era, and the most important thing for now is that Fallout 3 manages to improve on almost everything Oblivion did well, as well as what it didn't do so well - and how it streamlines a lot of the questing without resorting to dumbing-down. For a fair chunk of you, that's pretty much all you need to know.

Undoubtedly one of the most appealing aspects of Fallout 3 is the fact that the post-apocalyptic premise feels fresh - assuming the harrowing aftermath of thermonuclear war can be described as such. The fact that games haven't milked this theme to death is puzzling: rooting the game in the realms of potential reality gives the world credibility, with dozens of real-life weapons (from pistols to assault rifles) and near-future equivalents (think laser and plasma), recognisable locations, and relatively normal characters populating the world. There's even a series of local radio stations, belting out dubious propaganda or the rantings of the ever-exuberant Three Dog.

That said, the basic setting for Fallout 3 isn't exactly the down-to-earth playground I've portrayed once you dive into the fiction. It imagines a parallel version of America that remained locked in the cultural norms of the '50s, complete with the naivety, unflinching optimism and penchant for pre-rock 'n' roll. In this version of 2077, technology progressed to the extent that robot slaves populated every home, everyone drove fusion-powered cars down bold art-deco streets, fearing communism, wearing beehive hairdos and bopping along to happy jazz. Strangely, though, computer technology remained resolutely stuck in the late 1970s green-screen era.

Then it all went to hell at the climax of a long-running war with Communist China over Alaska, and the world went nuclear. 180 years later, literally at your birth, you join the game in the depths of a shelter known as Vault 101. The opening hour plays out as a wonderfully engaging run through the first 19 years of your life, through baby steps and petty infighting with the other children. With the sudden, unexpected departure of your father, you decide to fight your way out of the sterility of the Vault and emerge blinking into the shattered wilderness of Wasteland for the first time.

Stark freedom awaits you, in much the same way it did after emerging from Picard's dungeon in Oblivion - only this time under much less welcoming circumstances. The landscape is almost the polar opposite of Oblivion's lush green pastures, with a sea of grey and brown shattered rocks and ruined buildings stretching off into the distance. You can trudge to the nearest settlement, Megaton, or wander off wherever takes your fancy. There's no specific path to follow, and never is. You can either let the curiosity of your father's disappearance guide you through the game, or just explore.

The controls follow the standard first/third-person template, although, like Oblivion, first-person is preferable. As you might expect, enemy threats are never far away, and you won't get very far without facing some sort of mutant bug or ghoul. This, it turns out, is a good thing, as it shows of the first truly impressive aspect of Fallout 3: the V.A.T.S. The Vault-Tec Assisted Targeting System.

On one level it's a cinematic way of framing the combat in what is already a glorious-looking game, but this hybrid of real-time and turn-based combat also forces players into a new approach. Effectively you pause the action and decide on specific areas to target, whether it's head, torso, arms, legs or weapons. To help decide, each area is marked with the percentage chance you have of landing a hit, determined by the distance and angle of attack. At the start of each 'round', you have a limited number of action points to commit, which generally equates to three or more hits before the slow-motion combat reverts to real-time. Then your action points slowly regenerate, leaving you vulnerable.

Because combat is so fast and deadly in real-time, you find yourself forced to rely on V.A.T.S. in a measured, strategic fashion. You'll dive out of cover, slam it on, try and cripple a specific body part and get the hell away before the enemy can strike back. And if you're cunning, you'll find time to recharge your action points and repeat the process without wasting too much ammo or getting busted up.