S.T.A.L.K.E.R: Shadow of Chernobyl

Come in Reactor 4. Your time is up.

The roads north of Kiev are relentlessly bleak. A capital's spattering of wealth gives way to a dark, eastern European quaintness as the setting morphs to rural Ukraine outside the city, then to abject poverty. Farming towns turn to villages then to hamlets. Cow herds thin. Geese gaggles vanish. Blue painted roofs become fresh metal, as bright as can be expected under such a ghoulish sky, then holey rust. Broad-faced men with deep-set eyes stare back at us from monolithic concrete bus shelters. Shops sell nothing but dull oranges behind muddy glass. A woman wearing a torn floral headscarf sits in the heaving rain underneath rotting beams next to a milk bottle. She doesn't even look up. The coach thunders on. Humour peters out. There are no modern cars here, just 50s trucks and green ambulances hung-over from the USSR. The driver slows and we pass a road-sign bearing a right arrow. The word "Chernobyl" even looks ominous in Cyrillic.

The checkpoint is nothing like a Bond movie. It's a collection of concrete huts, sheet metal and a barrier a Lada could break. Men dressed in Ukrainian blue camouflage wear guns. We take photographs from a distance, but the downpour's so heavy it's a fleeting affair and we're forced back into our seats. A large soldier comes on board, glaring steel over the top of every passport, then leaves without uttering a word. A Trabant is met by another guard at the side of the bus; in its back is a girl and no seat. The greyness is insane, bludgeoning. A thin woman with a thick European accent rises slowly in front of the glass as the bus's engine drags us through the 30km border. Her nails curl round the headrest in front of me. I can't see her eyes.

"Attention please," she hisses. "We are now in the Zone."

HAPPYHAPPYGOGOTHQFUNBUS

While being in any zone at all may be something new to most of the inhabitants of THQ's happy-happy-fun-bus, for S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Shadow of Chernobyl developer GSC Game World the feeling's all too familiar. Estimates vary on how long the FPS has been in production, but "five years" is a safe bet. Heavily delayed – an original release date of 2004 sailed past with barely a whimper – many had thought the project lost until it reared its head at Games Convention in August. THQ has faith. Shipping 80 journalists to Ukraine from literally all over the world is no laughing matter. But the questions are obvious: can the game Eurogamer editor Kristan Reed described as "staggeringly beautiful" in April 2004 really cut it in a post-Half-Life 2 world? Hasn't S.T.A.L.K.E.R.'s time been and gone?

The answers aren't as easily available. Sitting down with S.T.A.L.K.E.R. today is an interesting experience. Firstly, the game's project lead Anton Bolshakov takes us through the much-publicised "A-Life" system. Read our interview with Anton . In a nutshell, S.T.A.L.K.E.R.'s machinations outside scripted level events are completely random. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.s – you play one – are men who hunt for artefacts in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, then sell them in the outside world. The other two major human "factions" in the game are the military and rebels, the fourth "mobile" element being the Zone's mutant population. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.s, militia, rebels and monsters roam between levels at will, constantly interacting with each other.

Anton enters a dev code and shows us a map of every living element in the game. He waves the hand of God and kills everything in one major area, then speeds up time. The level begins to fill with dots representing S.T.A.L.K.E.R.s, soldiers, and so on, which migrate from other areas. Dropping into 3D, he flies around the level as the various elements begin to clash. Hulking wolves eat a corpse, a remnant of a firefight. In another area, rebels and soldiers shoot it out. Levels never stay empty for long, says Bolshakov, and the whole A-Life premise adds massively to the replayability factor, he claims. He starts talking about "smart terrain," but we're cut short. In essence, GSC's ambition has been to create a living, breathing world to surround the overarching storyline. "Oblivion with guns" is a simplistic description, but you get the idea.

www.prypiat.com

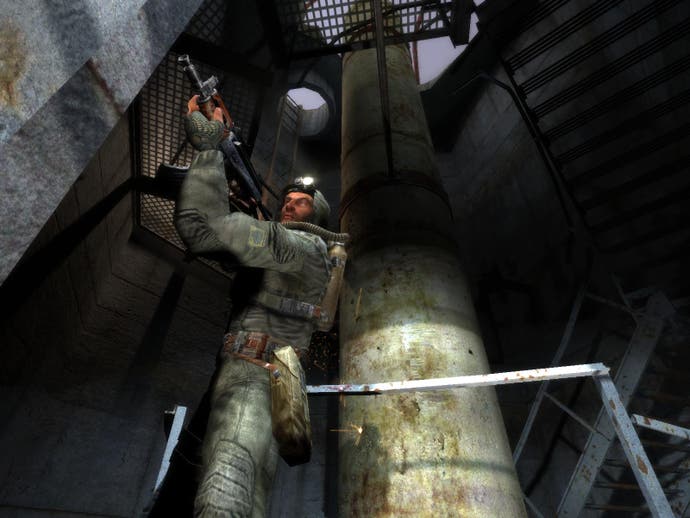

Hoisted away from the AI demo, we find an empty chair and get to play. It's a level set in Prypiat, the town built to house workers at the Chernobyl power plant. There's no disguising it: S.T.A.L.K.E.R. does looks dated. The level sees you start with a squad of NPCs taking out snipers, and the modelling on your compatriots could never be described as "cutting edge". But we're talking here about a completely open-ended game with 60 hours of play and a massive area. It certainly looks better than adequate, just "2005" as opposed to "2006". Remember Operation: Flashpoint? Graphics didn't matter then, did they?

Gameplay, however, does. I literally had 10 minutes with this level. The NPCs barked at me in Russian accents, and I got a taste of the PDA mission system and Diablo-style inventory ordering, where you drag and drop weapons and equipment into slots after pulling up the system by pressing "I". It was fun. I shot people in the head and threw grenades over wrecked cars. I found I could pick up any weapon produced along with a corpse. I even grabbed one AK-47, equipped it, went to kill an enemy and found it needed loading.

Leaves blew around and the wind sounded suitably eerie. Prypiat itself, the buildings and furniture, looks fantastic.

And I'd know. Standing in the middle of Prypiat as the sun sets is like being in a horror movie, no more or less. It's bloody terrifying, truth be told. Prypiat housed 50,000 plant workers in the 80s, the residents of which were given three hours to gather essential belongings then marched onto buses after Reactor 4 went ballistic. The buildings are still standing, and are faithfully represented in S.T.A.L.K.E.R., particularly the large supermarket at one end of the main square. Our guide tells us that the shopping in Prypiat was among some of the best in the Soviet Union, and wages for workers at the power station were twice the USSR average. Don't leave me at any time, he says. There are wild wolves here. My friend was attacked by three wild wolves. This is not a joke.

We're not laughing, mate.

We see the gym, the swimming pool, the floor strewn with Russian books. We see the dodgems and the Ferris wheel. We see a sign for Prypiat.com, the site devoted to the ghost town run by those who left as children. We see the notice board covered with pictures of Soviet volleyball players and the murals of women embracing each other in circles. We get lost (honestly) in the middle of the municipal building and fair near shit ourselves before finding the rest of the group. We marvel. It's an awful monument. The whole place is built of menace. You long for space, for fields and trees.

"I'll have an AKS-74 and a Franchi SPAS 12, ta."

Luckily, stretches of countryside are something S.T.A.L.K.E.R. has in spades. Ushered on from the Prypiat level, we play something far more open. Walking through the real Zone's fields wouldn't be so great for the feet (or any other part of you) as organic matter holds far higher levels of radioactivity than concrete, but there are no such worries in the game. If you wander near an "anomaly" in S.T.A.L.K.E.R. your personal Geiger counter goes berserk and your health drops. The reality is a tad grimmer.

The new level starts on a country road. An NPC tells you the militia is storming a compound and it's your mission to help other S.T.A.L.K.E.R.s. Seems there's a traitor in the brotherhood's midst. Helicopters fly overhead, firing rockets at buildings as you charge forward. We play this section for about half an hour, and die a few times. Each time enemies come from different angles, and the AI seemed tricky enough. Second time out we take the time to walk right round the compound (which is massive) and find, to our delight, that we're rewarded by finding a different way in through a broken wall.

Kill the soldiers, someone shouts in my ear. I do, and they're not so easy going on me. Ammo becomes a precious resource. Graphically, the indoors areas look far more advanced than those outside, flashlights picking up bump-mapped walls and showing some lovely real-time shadowing.

I clear the area and brainlessly shoot the mole I was supposed to question, then start fannying about with the game, taking a closer look at the inventory system. If you click on any item, a description appears in a central pane. Weapons have accuracy, damage, handling and rate of fire characteristics, and each has a cost. Anton mentioned that a trade system was in place in the game, but we never see how this works. For example, an AKS-74 or a Franchi SPAS 12 will set you back 2,000 roubles. A Heckler and Koch MP5A3 costs 1,100. Other items are listed in the character's inventory, such as the "Tourist's Breakfast" for 100 roubles and "Diet Sausage" for 50. And there are packs of bullets: .45 ACP ammo costs 200 roubles. Seems GSC has thought of everything a self-respecting S.T.A.L.K.E.R. might need.

Clicking on the only other mission available in the PDA brings up a point on the map literally miles away. Following the direction arrow out of the compound, I'm soon in the middle of a firefight between bandits and soldiers. I want to explore. I want to see more. I want to go to the middle of the Zone. Sadly, there's no time. Not in the game, anyway.

Shock and awe

"Jesus Christ," whispers the THQ PR lady. "Can we get any f***ing closer to it?"

The sentiment's echoed in virtually every face on the bus. Unbelievably, we're no more than 200 metres from Reactor 4, the site of the worst nuclear accident in human history. We're taken into a visitors' centre across the rail tracks from the "sarcophagus," the concrete shell erected over the exposed reactor core in 1986. A Ukrainian lady talks us through the time-line of the disaster using a model of the plant. On the wall is a massive Geiger counter. The rain's stopped but the day is as grey as porridge. I don't listen. I can't stop staring out of the window. We're not in the area for more than 20 minutes, for obvious reasons. We're allowed to take photographs outside the centre, not of the panoramic view afforded inside because of "national security". I take some of the guide standing in front of the reactor, and we're the last to return to the bus.

"It's amazing we're allowed so close," I say as we walk back. He flashes me a well-meant sneer.

"It's not amazing," he says flatly. "The people that work here earn about $400 a month. That won't be enough money to rejuvenate their health."

And there it is. The emotion I was hoping I wouldn't feel on this trip: shame. There are men lifting girders and digging sand in front of the ruined reactor, their expressions at our interest far, far beyond gallows humour. We're a bunch of over-privileged idiots stamping over hopelessly tragic history like it's Disneyland because of a computer game. I realise how patronising I've been and I want to apologise, but don't. He wouldn't appreciate it.

Misjudged sentimentality aside, my lasting memory will be standing in the centre, staring out of the window straight into the dead face Reactor 4. It's so much more than a building, in the same way the Statue of Liberty isn't just a statue. It made my hair stand on end. That crumbling, grey escarpment represents the grand folly of Soviet communism in such a complete way that the intense sorrow radiating from its cracked walls is its perfection. And, watching the clouds roll behind the reactor's tower, I don't feel fear, or shame, or horror: I feel awe.

Nuclear end-game

Will S.T.A.L.K.E.R. be able to evoke the same reaction? There are a lot of ifs, but as I said, the answer's nowhere near as cut and dry as some would like to believe. The code we saw wasn't finished. There were obvious frame-rate issues and it crashed on us twice in 40 minutes. But S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is not an average first-person shooter. It's a massive, open-ended first-person RPG with extensive non-scripted elements. The question is whether or not the whole thing will actually work. We saw it for so little time that it's impossible to tell. If the scripted levels are strung together coherently, if the combat AI proves to be ultimately challenging and intelligent, if the A-Life system really does make the game-world feel full and vibrant, then yes, potentially S.T.A.L.K.E.R. could be a real winner.

But if, five years on, GSC and THQ have got this wrong, they're going to be left with something very big and very costly. Fingers crossed this isn't going to be the second Chernobyl disaster, then.

The to-be-confirmed release date for S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Shadow of Chernobyl is March 2007.