Rewriting history

Replay author Tristan Donovan on why games began with the atomic bomb.

Tristan Donovan's book Replay: The History of Video Games is arguably the most entertaining overview of the industry that has yet been written. Charting the growth of games from the genesis of modern computers in the Second World War right through to the explosive return of bedroom coders in the last few years, it's exhaustive, detailed, and full of fascinating asides. Eurogamer caught up with Donovan to learn more about his work.

What got me thinking was that I bought a copy of Steven Kent's book, which was the first one to really try to be a complete history of games. I respect that, but it's very American in its focus.

The Spectrum didn't exist. The Amiga didn't exist. All my personal gaming history as someone who grew up in the UK just didn't exist from the perspective of that book. That got me thinking that there was still an untold story here. I don't think it was particularly good on Japan, either. It's very US-centric.

I started thinking that someone should do this. After a couple of months of thinking that, I figured that, well, I'm a writer, I've written about games, why don't I do it? It came out of that, really. I felt there was a better history of videogames to write.

I've also always had a problem with the way game history is represented. It's very much kings and queens: you have different console generations and that's the dynasty that you follow.

But, you know, that's just hardware. That's not the magic of games. The magic of games is the entertainment they offer – the actual creative work that goes on those platforms.

To me, this console-based approach was a bit like writing a history of music where you first write about vinyl, and then about cassette tapes, and then about CDs and then iTunes. That doesn't tell you anything about how music evolves. These were the things I wanted to, I suppose, correct. Or at least push gaming history more in that direction.

Well first of all, it makes it a lot more difficult to write. That was my first lesson. But I think what you end up doing is looking for themes. You end up not necessarily looking for what was the popular game, but for which game might be influential to game designers, or the things that were outside games that fed into people's thinking.

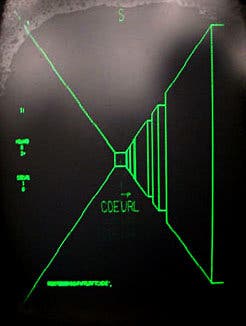

You realise trends are a lot more fluid and you lose that logical progression that's a little bit artificial. You get things like Maze, which is arguably the original FPS, which came out in the early 1970s. Then you have a few things which go in that direction in the late 1980s. And then eventually you get Doom, where it really kicks off.

But the thing is, you've suddenly got this long, expansive evolution process for a thing that everybody says kicked off with Castle Wolfenstein. It's actually a slow progression that just eventually gains a lot of momentum.

So you find a lot of these storylines actually cross over and get mixed up. The difficult thing is to try and make sure it all makes sense. It's really like talking about prog rock, synth, and 80s glam metal: they all cross over, but they've all got different points of origin and pathways.

Game history becomes a lot more like that, and you realise videogame genres aren't so distinct. It's a lot more creatively messy than people give it credit for.

Yes and no. Very early on the markets all did their own things and they all went off in their own directions. So you had France with these geo-political text adventures, us with Jet Set Willy and sheer insanity, and Germans with managerial, strategy types games. Of course, you still had these arcade games and other titles that just transcended all that and appealed everywhere.

But then as the games industry's globalised, that's become less and less visible. Japan seems, in a way, to be one of the last strongholds of national identity in games.

You still get the odd flavour, though. Fable, for example: that's definitely English, and Grand Theft Auto. Underneath all the trappings, there's this slight anti-consumerist message, which is quite a British way of looking at things. Quite a left-wing approach. It would be quite easy to play GTA and not pick up on that, but it's definitely in there.