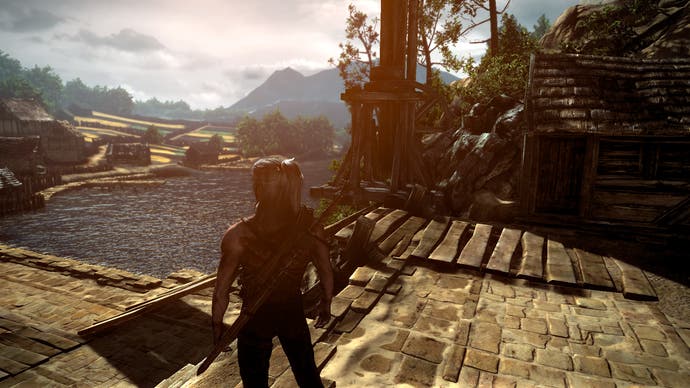

The Witcher 2

400 year-old Vergen.

I'm an explorer at heart. I'm never happier than when I'm lost in a world that exists for its own sake, rather than as a fleshed-out backdrop for 20 predetermined hours of linear derring-do.

Content to spend countless hours picking daisies in the name of alchemical self-sufficiency, I crave the matryoshka mentality of game design where layers are peeled back slowly, a word spoken with the wrong person invokes unexpected back-story, and randomly discarded books open up a whole new chapter of quests.

So it I find myself in danger of missing the meat and bones of The Witcher 2 during Namco Bandai's preview event. Yes, I know the men of Vergen have started to go missing, and satanic stitch-craft has been etched onto the bodies pre-mortem. I'll get right on it, I swear.

It's just this bearded dwarven bastard has upped the ante in the arm-wrestling stakes, while a mysterious and buxom trader has an investigation for me. I'm already late for fisticuffs by the fireplace.

Non-linearity continues to be the driving force behind development of this sequel. A heavily-modified Aurora Engine has been eschewed in favour of a brand new, in-house proprietary system. This has allowed the team to take more hands-on control over balancing, the development of non-linear quests and debugging.

The side-quest we're presented with is a case in point. After discovering the gruesome remains of one victim, deep within the stone ruins of the Vergen catacombs, a detailed examination reveals something embedded within the festering corpse.

At this point in the game Geralt lacks the necessary tools for extraction. So it's a tantalising example of the piñata approach to quest development: a box of delights, filled with unfinished business for the determined explorer.

The new engine has also given a shot in the arm to what was an already impressive visual rendering. Free to experiment with an architecture left largely uncommented on in Sapkowski's books, CD Projekt has taken to the task with vigour.

Vergen is a town hewn from the rocks surrounding it and held together with wooden foundations. It houses a population that lives with the land rather than on it, striving for rugged survival rather than unnatural domination.

The world at large is still a pre-NHS, medievally Nordic place where men are men, women are glandular receptacles and syphilis continues to claim several hundred thousand lives a year.

But the sex cards are out - and good job too. We're still at that awkward, fumbling schoolboy stage when it comes to dealing with the finer points of adult relationships. For many, the romance cards of the first game stepped over the line between a refreshingly adult Brothers Grimm-style fantasy, free of excitable gnomes, and into the territory of sniggering titillation.

I'm not trying to burn any bras here. I just long for the day when I can tell people what I do for a living without receiving a hurriedly stifled look of pity in exchange. Reference a sex-card collection of conquests and you'd be forgiven for assuming they belong to either a recklessly well-organised serial killer, or the kind of guy who believes he's likely to find a soul-mate by going on Take Me Out.

I think we can do better than this, bawdy world or otherwise. Tomasz Gop, senior producer at CD Projekt, agrees. "A lot of people thought it definitely did not fit the overall feeling of the game - collecting women," he says.

"No-one's surprised that sex is part of the game, and it fits the world. It was just the presentational aspect they complained about - probably they were right."

Combat has not so much evolved as mutated into an entirely different animal in the years since the first game launched. Gone is the turn-and-timing combo system that seemed at first glance to encourage - but ultimately punished - furious clicking. It's replaced instead with an action-orientated system that's more fluid and delivers a stronger bite.