Anomaly: Warzone Earth

Clothes make the commander.

There's this famous scene in the movie Patton. No, not the one where he stands in front of the American flag and talks about shooting the Hun in the belly. I'm talking about the scene where two tanks get stuck in mud during the Third Army's march across France, and General Patton hops out of his Jeep to direct traffic. The image switches to a close shot of Patton, and he's beaming. He revels in his conception of a great commander: one who's willing to put his own boots in the muck.

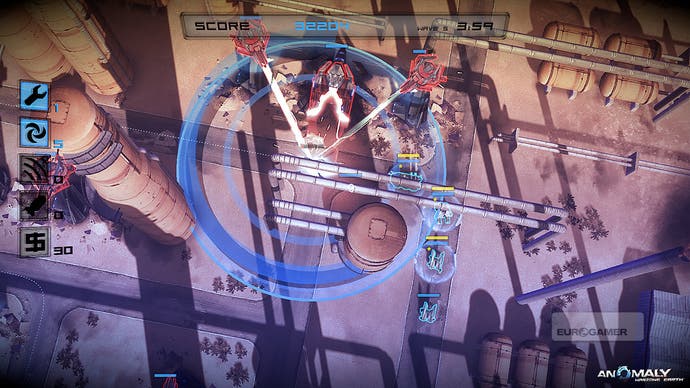

In Anomaly: Warzone Earth, you play a traffic cop in the Patton mould. When an alien invasion sets down in Baghdad, you're the commander on the ground, scampering around the battlefield in an exhausting effort to will your convoy of tanks and missile launchers into victory. Your character never fires a weapon; in fact, you're the tiniest thing on the screen – a mere mortal dancing through massive weaponry. Yet at the end of a battle, the smoking earth seems to bear your outsized thumbprint. Now I see what Patton enjoyed so much.

Anomaly is a reversal of the standard tower defence format: the evil, faceless aliens place towers along a path, and your troops attempt to survive their gauntlet. The switcheroo could be considered a gimmick if the developers at 11 bit studios weren't so clever about it. They haven't simply swapped roles; they've re-engineered the form.

Most tower defence games play out the same way: You construct a defence and then brace yourself as the marauding hordes approach. Since you can only make minor adjustments on the fly, the formula is 80 per cent preparation, 20 per cent improvisation. The makers of Anomaly asked, what if you switched that balance? And so they've produced a game where strategy still matters, but it's beholden to the second-by-second reality on the ground.

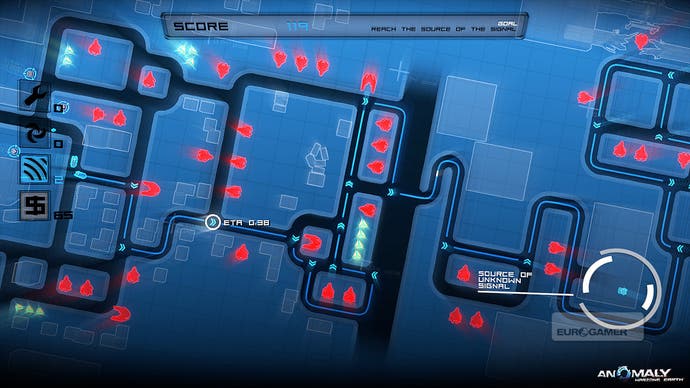

Each stage opens with the wide view, a map of the urban grid that you have to traverse. The setting is Baghdad in the first half of the game and Tokyo for most of the latter half. You view the cityscapes from directly overhead, with images seemingly based on satellite imagery. It's a look reminiscent of The Last Guy, albeit with more of a shiny Michael Bay sensibility.

As you scan the map, a man on the radio gives you some vaguely military-sounding reason you're about to plunge into hell – like, say, gaining control of a radar complex. OK, fine. You plot a path through a section of the alien-occupied city by drawing a dotted line on the map that will serve as marching orders. You choose your units, creating a balanced fighting force. Then you say "go." At this point, you start throwing out your stupid plan that was never going to work anyway.

The dotted line is a farce. You'll adjust and redraw it countless times over the course of a level, for myriad reasons. Maybe a bridge gets knocked out, or your need to backtrack and pick up some loot you missed. Often, the aliens spawn new turrets in a formerly peaceful-looking corner of the map – those smooth stretches of this pockmarked landscape are always tempting, and as such they ought to arouse suspicion. Thus you take a new tack, and another, and another. If you were working with pencil and paper, the map would be a mess of smudges and sweat by the time you reached the finish line.

Your army is a work in progress, too, thanks to your penny-pinching masters back at Anonymous Military Entity HQ. Before launching an assault, you receive a bit of pocket change with which to purchase a skeleton crew: maybe a couple of rolling gun turrets. Knocking out a few towers with this sorry platoon earns more money, and you add units so that you can take on the bigger targets. The new units drop from the sky, and into perfect parade formation, the instant you buy them. It's best not to question the logistics here.