Disabled and Hardcore

The story of the man behind Call of Duty's N0M4D controls.

"Is this a joke?"

The first day of the 2007 Major League Gaming tournament in Charlotte, North Carolina, was mere minutes away from starting but for the team asking the referee if they were the butt of an elaborate prank, excitement had given way to surprise.

As they looked on slack-jawed, their rivals from the H2O gaming clan were preparing to do battle in Rainbow Six: Las Vegas. Or, more exactly, they were getting team member Randy Fitzgerald, aka N0M4D, ready.

Fitzgerald was born in 1979 with arthrogryposis, a rare condition where underdeveloped muscles cause the joints in the arms and legs to become frozen in position. Put simply, Fitzgerald cannot move his arms, hands, feet or legs.

To get around this, Fitzgerald plays games with his face by using a customised controller held to its right-hand side by a stand that screws into his wheelchair. As his H2O team mates set up Fitzgerald's controller, the referee confirmed to the other team that yes, the guy in the wheelchair would be playing. Sensing an early victory, H2O's rivals smirked and teased.

The opening match was just moments away now and as the start time approached, Fitzgerald turned to his team and said: "Let's kill these guys."

And kill them they did. "We ended up just destroying them," recalls Fitzgerald.

It was no one off. Team after team fell at the hands of team H2O. Soon a buzzing crowd of spectators had gathered around them, all trying to get a glimpse of the man who played with his face as he wiped out challenger after challenger. "There were so many people taking pictures that the flash was starting to hurt and it was hard to focus on the screen," says Fitzgerald. "We ended up winning for the whole day, and if you make it to the second day you're considered pro."

H2O may have been knocked out in the first round of the second day, woozy after a night celebrating their earlier victories with a crate of beer, but N0M4D's performance had become the talk of the tournament.

Fitzgerald, now 32, started gaming early. "I was about three. My dad used to go to the bowling alley with his friends and take me along. The alley had an arcade and my dad would pull a pinball machine in front of the Pac-Man machine, take me out of the wheelchair, put me on my stomach on the pinball machine and put a quarter into Pac-Man and I would move the joystick with my chin."

Soon those quarters were lasting for hours. “One year my dad entered me in a local Pac-Man tournament and I came second or third," he says. It didn't take long before Fitzgerald was supplementing his arcade conquests at home with an Atari 2600 and miniature tabletop arcade machines produced by the likes of Coleco.

"My parents realised there's not a lot of activities I can do with my disability, so they really supported the whole gaming thing right off the bat," says Fitzgerald. "They bought me a lot of video games and every new system that came out. So I had a lot of practice."

Not that the transition between consoles was always smooth. "When I went from the one-button joysticks of the Atari to the NES with a d-pad and two buttons I remember feeling very frustrated and thinking how am I ever going to play that?"

Fitzgerald's solution was to rotate the controller 45 degrees clockwise so he could manipulate the directional pad with his top lip and use his chin to work the A and B buttons. That approach worked, with only minor adjustments, all the way until the late 1990s when the Sega Saturn forced another rethink. "I learned to flip the controller the other way so that I would be using my chin to flip the d-pad and my top lip to hit the other buttons. That's how I've been playing ever since."

Fitzgerald feels his abilities as a player are as much due to many years of practice as any innate talent. In fact he seems a little uneasy about his reputation as a 'pro gamer'. "I never used the term until Major League Gaming started putting articles on its website talking about how I was pro. After that everybody else started calling me pro," he says. "I don't know. I think I'm... alright. I see other people who are better than me."

Regardless, his playing prowess has certainly inspired others. "There's quite a few disabled gamers that play tournaments now, but I was the first. I get a lot of emails from other disabled individuals that say 'thank you so much, you gave me the courage to go to this tournament'. I feel good about that.

"But it's a hobby - I don't plan on making it a career. Some of these 15-year-old kids crack me up. They send me messages asking how to become a pro gamer and I'm like: 'Kid, you can't go into this thinking it's a career'."

Career-wise, Fitzgerald's real plan is to open his own game development studio. "I went to college to study game design and development. That's my real passion: I like making video games."

While a period of serious illness has meant he had to delay completing his course, he has already registered the name Nomadic Games and is close to finishing his first game design documents. "I know a lot of people in the industry, including the people at Infinity Ward, and they're waiting to look at these documents and are going to help me shop around for a publisher that will hopefully give me the money to hire a team to make these games," he says.

Fitzgerald's links with Infinity Ward are close, not least because he has had a direct influence on the last five Call of Duty titles.

Back in 2006 when Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare was still in development, Fitzgerald and Infinity Ward's creative strategist Robert Bowling got to know each other while writing E3 blogs for Microsoft.

So the following year Bowling invited Fitzgerald to try out the beta of the game that would turn Call of Duty into the commercial juggernaut it is today. Fitzgerald loved it: "It was really fresh at that time with things like killstreaks."

But there was a problem. The toggle aim option included in Treyarch's Call of Duty 3 was nowhere to be seen. "That option made the game easier for me as instead of having to hold the left trigger, you just tap it to raise or lower your gun," Fitzgerald explains.

Figuring he should see if others felt the same about its loss before raising the matter with Infinity Ward, he asked members of Call of Duty's CharlieOmegaDelta forum for their views. "I thought maybe a couple of people would go 'oh yeah, me too', but I got 25,000 replies within a couple of days," he says. "Every second somebody was posting something new. I don't think I slept for two days as I was reading all the messages and trying to reply to everybody. It was crazy."

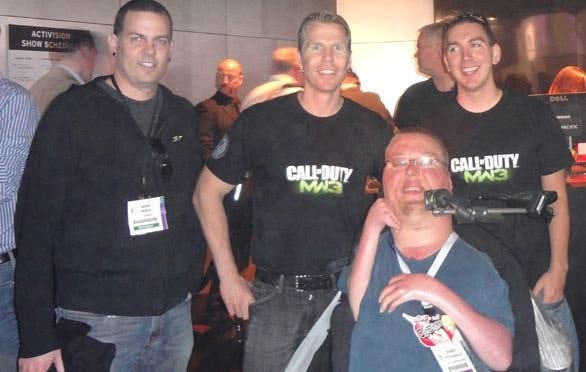

Within days Infinity Ward had taken note and promised to reintroduce toggle aim in a patch that would add a new control option named N0M4D in Fitzgerald's honour. Since then every Call of Duty has included the N0M4D control scheme, except Modern Warfare 2, where a bug forced its last-minute removal and the subsequent sackings and walkouts at the studio meant a patch never happened. Infinity Ward has, however, confirmed the N0M4D controls will be included in Modern Warfare 3.

Having already left his footprint on pro gaming and Call of Duty, Fitzgerald is now more focused on his future as a maker of games. It's a journey that reflects the meaning behind the Minnesota resident's gamer tag. "People think I chose N0M4D because a nomad walks around and it's ironic because I'm in a wheelchair, but no. My reason is more philosophical. My version of a nomad is someone who travels the Earth searching for their purpose in life and along the way stops in villages and towns and shares their experiences before moving on. I think that's me. I'm a person still searching for their purpose in life and whatever I learn I share with people. So I figured the name suited me."

And others clearly agree: now when Fitzgerald goes to competitive events, he's met with respect in place of the bemusement that met him back in 2007. "A lot of people don't even know my real name," he says, "I'll go to a tournament and it won't be 'hey Randy how you doing it?' it's 'hey N0M4D, what's up?'"