Gunpoint Preview: Rewiring the Action Puzzle Game

How Deus Ex inspired an indie game about electricians.

Several months ago Tom Francis, whom you should know from his writing for PC Gamer, went to Seattle to interview the team at Valve. When he sat down with Gabe Newell and Erik Wolpaw, something really weird happened. They asked him how his game was coming along.

His game, as it happens, was coming along pretty well. I saw a rough demo of it at around the same time, and I've just now played the newest version, which has art by John Roberts and Fabian van Dommelen, music by Ryan Ike, Francisco Cerda, and John Robert Matz, a new mission structure that ties its individual levels together in a witty fashion, and an IGF nomination for excellence in design. Newell probably wants to kick him in the nuts, frankly.

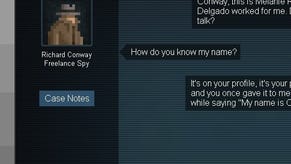

The game's called Gunpoint, and it's a stealthy action-puzzler in which you play a secret agent for hire, breaking into hi-tech buildings and stealing various cyberpunk MacGuffins. It's the future as rain-slicked corporate nightmare, but the game looks more like The Spy's Guidebook than Bladerunner. Meanwhile, with its 2D cross-sectioned levels and flashes of nasty humour, it feels a little like a grown-up version of Bonanza Bros. And that's a compliment.

At heart, it's all about screwing with systems and messing with AI guards, and it grew out of the way Francis tends to approach games as a player. "I guess I keep thinking there's some simple, efficient way to capture some of what I love in my favourite games, and try doing something new with it," he says. "I can't really make Deus Ex 4," - not with that attitude, buddy - "but I feel like I've analysed what's good about Deus Ex so many times that I can sort of isolate the principles, and come up with something I have the resources to produce that works on some of the same ones."

In Gunpoint, most of the fun comes from hacking. Armed with a tool called the Crosslink, you can sneak into your quarries' plush HQs, and rewire doors, light switches, security cameras, elevators and all manner of other elements of the environment in order to open up a path to the data terminal you've come for - or to aid you when tackling any nearby security personnel.

"That came from analysing what I like about Deus Ex and BioShock," says Francis. "I love it when games let me subvert the levels to work for me. But if you forget that it's rare for games to let you do that and if you just look at the bare mechanics, even in those games it's pretty limited. It's just turrets, cameras and doors, and the subversion is just flipping them to your side. I didn't feel like making you play a PipeMania minigame really expanded on that in an interesting way.

"I got thinking about when I used to make levels, I think it was for Quake 2, and I learned how to link up switches and doors and stuff," he continues. "You could just take any device and specify which other device it should trigger. It was a mind-blowing amount of freedom. Since that's how games work under the hood anyway, why let the level designer have all the fun? Why not give the player the power to tinker with that stuff?"

The result of all that thinking is a game in which a lot of player freedom emerges from a few basic rules: once you know how things work, in other words, you can approach your objectives in a number of ways.

Let's take a simple scenario: a two storey building with guards, security doors, and security cameras between you and the data you've come to steal. You can probably get quite a long way by sheer gymnastics alone. In Gunpoint, you use the left mouse button to charge a jump, and a simple arc shows you where you're going to land when you release it. That jump is nice and generous thanks to your Bullfrog projectile trousers, and you'll stick to walls and ceilings with no fuss, and can crawl up and down, high over peoples' heads, using your Slapstick adhesive gloves.

Traversal's been made simple and painless, perhaps, but you still feel spring-heeled and deadly. Dropping onto a standard guard allows you to pin him and then club him unconscious, as long as he doesn't see you and shoot you first, and even heavily armoured enforcers can be knocked backwards out of windows if you hit them hard enough. You can't die by falling, but they can.

That may sort out the human element, then, but those cameras and doors are still going to be a problem. Enter the Crosslink. This allows you to wire a light switch to a security door, for example, bypassing the hand scanner that only guards can use. You could also rewire the security camera to the security door, meaning you only have to step into the camera's viewing cone in order to get to your target. The interface is uncluttered and intuitive - you just drag beams of light from the object you want to act as a trigger towards the object you want that trigger to activate - and the whole system's bristling with opportunities, especially when you start to factor in enemy AI.

So if a guard is standing watch over a crucial door on the floor below you, you can use a rejigged elevator button, say, to switch his level's lights off, making him head for the nearest switch while you sneak past him. Or you could rewire the security door he's standing in front of, sending it slamming into him and knocking him out cold.

Guards are stupid but predictable - give them a specific situation more than once and they'll always behave in the same way, meaning you can toy with them more reliably. On top of that, the game throws in promising concepts like the Longshot, which lets you rewire enemy guns to other elements of the environment, booby traps, and even levels where switches are linked to different colour-coded circuits and can't be cross-wired from one set to another.

"As a player, I love any game that gives me a set of rules where the designer can't predict everything I might do," says Francis. "As a designer, I'm really enjoying creating a set of rules the player can surprise me with. They already have: testers have done hilarious things I'd never thought of, like tricking one guard into unwittingly locking another inside an office."

Gunpoint's individual levels form chains of missions that you receive from a series of clients. In between jobs there are upgrade points to spend, and a shop, where you can buy new gadgets. Most missions come with optional objectives, too: they might reward you for not killing a certain guard, say, or leaving without being spotted at all.

"I feel like the exciting part of espionage is causing a large-scale change by doing something quite subtle," explains Francis. "You never have to kill anyone, though you certainly can. And you don't have to pull off perfect stealth. If you like getting a pat on the back, though, some clients definitely prefer an agent who can get in and out without ever being seen. That turns out to be much more tense and fun than I expected: there's a silent satisfaction to using subterfuge to avoid violence entirely."

Gunpoint's current release date - and it's extremely current, if that's grammatically possible, as Francis just IM'd me with it - is "later than May". Just like Half-Life 3, then. You're going to be paying for it, incidentally, but he hasn't worked out how much it will cost yet.

What he has done, though, is build a framework for a puzzler that rewards cleverness and convoluted sadism in equal measure. JC Denton would be proud.