Phil Harrison: The Real Next Generation

Microsoft's new dev boss has taken a circuitous route to the role. What will he bring to the job?

Rewind to the heady days of '05 and '06, when this generation was still 'next generation'. At trade shows and press events around the globe, giants of industry from Japan and the United States pace around each other warily: Sony and Microsoft, each looking for an opening for a killer blow. For decades, console wars had been fought between rival Japanese firms. This time, the foes faced each other across the Pacific.

It was always tempting to characterise Sony and Microsoft's battle in national terms, Japan versus America - but that was never a useful way to frame the battle, because companies that size outgrow national borders. That fact was very clear when you sat down with Sony or Microsoft to talk about their respective endeavours. No matter whether it was the Japanese firm or the American one with whom you had an audience - the person each one chose to be their figurehead was British. In the Microsoft corner, Peter Moore. In the Sony corner, Phil Harrison.

The games business merry-go-round spins. Today, Moore is COO of EA - and Harrison has just been appointed as head of Microsoft Studios' European wing. At Sony, he was Head of Worldwide Studios, so he's effectively crossed the floor to a similar position at his former arch-rival - although he took a rather circuitous route to get there.

Harrison is a divisive figure. His replacement as Worldwide Studios boss at Sony, Shuhei Yoshida, has maintained a lower profile but is almost universally liked - he's seen by journalists, gamers and industry types alike as honest, enthusiastic and open. Harrison, though, still gets a mixed response, even though he's been out of the console business for the past four years. Those who have worked with him speak highly of him as an intelligent, professional and extremely dedicated executive - and Microsoft obviously concurs with that judgment. For some gamers, though, Harrison has come to be a symbol of how arrogant and out of touch Sony was at the start of this generation.

That's a result of the rather unusual position in which Harrison found himself around the time of the PS3 launch. Although he became the de facto spokesperson for the PlayStation 3, his actual job was to oversee the development of software for the console - in September 2005, he became the first president of the newly formed Sony Computer Entertainment Worldwide Studios, an internal organisation that brought all of the firm's studios in Japan, Europe and the USA together for the first time.

Harrison was the right man for that job. He was one of Sony's earliest gaming hires, having joined the company back in 1992 - two years before the PlayStation launched in Japan. He'd started out as a graphic artist and game designer, and had worked at Mindscape, a British publisher, as head of development for five years. His new job was to convince European publishers and developers that Sony was serious about videogames, while also building first-party development studios for Sony in the UK. It's no exaggeration to say that Harrison was an important figure in the success of the PlayStation. Perhaps the most notable thing to happen during this tenure was the acquisition of legendary Britsoft developer Psygnosis, which went on to create the WipEout series - landmark games which helped to establish the PlayStation's unassailable market position.

In 1996, with PlayStation on the market and well into its meteoric rise, Harrison moved to the United States. Appointed as Vice President of Third Party Relations and Research and Development, he reprised the dual role of inducing third party developers to work on the PlayStation, while also overseeing SCEA's internal development teams. He stayed in the USA until 2000, when he moved back to the UK ahead of the PlayStation 2's launch, and spent the next five years once more overseeing European development, before being anointed as head of the company's worldwide development efforts in 2005.

Despite Harrison's pivotal role in the success of both the PlayStation and the PS2, 2005 is probably the point at which most gamers became aware of him. Along with his promotion to Worldwide Studios boss, Harrison became the public face of the PS3 ahead of its launch - appearing on stage at E3 and GDC press events, as well as giving seemingly endless interviews. Initially, he just talked about software, and seemed keen to keep things that way. But as dark clouds started to gather over the console's launch, he was increasingly drawn into talking about the hardware, the strategy, and - perhaps worst of all - the often bizarre statements being made by his bosses in Japan.

It didn't help that Harrison's major public debut was Sony's E3 2005 press conference, where he presented stunning videos of games and tech demos for the freshly unveiled PS3 - all of which turned out to have been 'target renders', rather than code actually running on the system. Harrison intended no duplicity - he openly told journalists after the conference that the footage was rendered, not real-time. However, the contrast with Microsoft's conference - where the company showed underwhelming but honest footage of in-development games - left Sony looking duplicitous and underhanded (as well as leaving many journalists, myself included, looking a bit thick for praising Sony's display).

Half a decade later, no game publisher would dream of showing the world half-finished real-time footage running on non-final hardware - "target renders" are now the standard (and thankfully, console games today look a lot more like Sony's target renders than Microsoft's frankly awful-looking footage). It hardly mattered. Harrison seemed untrustworthy, as did Sony as a whole - and many of the journalists who'd felt hoodwinked by Sony's renders were determined to give the company a hell of a hard time for it, too.

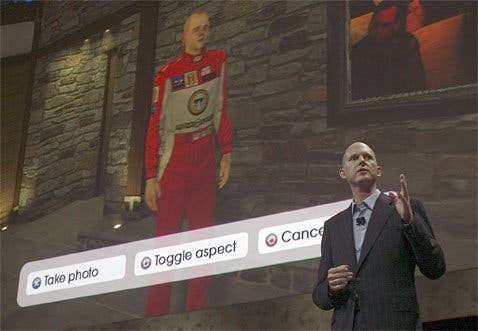

In the months and years which followed, Harrison was constantly in the public eye. He was at his finest when he was able to simply talk about software - such as his enthusiastic demonstration of LittleBigPlanet at 2007's Game Developers Conference. Both on stage and in interviews, however, he rarely seemed comfortable - often hiding behind a kind of impersonal corporate speech which allowed him to dodge tough questions about the PS3's difficult gestation and launch, but not without looking exceptionally slippery in the process.

If you spoke to Harrison off the record, he could be blunt, direct and extremely honest - displaying, in fact, most of the virtues which have made his replacement, Yoshida, so popular. He knew the PS3 had problems, and once the recorder was turned off, he'd openly discuss them - and made clear how he felt about the pronouncements falling from the mouth of Ken Kutaragi (remember how we were all going to get a second job to pay for an overpriced PS3?).

On the record, though, he had no choice but to defend the company and its bosses - and where Peter Moore was superbly adept at sticking to the corporate line while also sounding chatty, interesting and human, Harrison came across as stiff, formal and, well, a bit smug, to be honest. Perhaps he just didn't have Moore's natural talent as a raconteur (of all the games executives I've interviewed, Moore remains easily my favourite interviewee), or perhaps this is just a difference between Japanese and American corporate culture - it'll be interesting to see what his interviews as a Microsoft executive are like.

There was another factor at play, though. It seems that Harrison wasn't just put out at having to defend the indefensible things being said by executives like Kutaragi back in Japan - he was also, at least to some extent, at loggerheads with SCE's Japanese management. They'd handed the reins of Worldwide Studios to him, but Tokyo never quite saw eye to eye with Harrison on his most ambitious idea - the attempt to make the games console into the centre of the living room for the whole family.

As the PS2 entered the late stage of its life, Harrison had realised that the incredible sales of the console meant that it had an opportunity to reach people who'd never previously considered themselves to be gamers. Harrison focused Sony's European efforts on building the kind of games which we'd probably now think of as 'social' or 'casual'. Eye Toy, SingStar and Buzz were the main results - games that used cheap add-on controllers to entice people intimidated by complex controls to give games a go. They worked, in Europe at least, selling by the bucketload and turning the PS2 into a gateway device for 'casual gamers'.

Outside Europe, though, Sony never got behind the idea. Promotion for SCEE's social titles was half-hearted at best, and in an omission that seems mind-boggling even now, SingStar never even got a release in karaoke-obsessed Japan. At GDC in 2008, with his departure from Sony imminent, Harrison revealed that Japanese colleagues had told him bluntly that there was no market for social gaming in Japan. Their reaction when Nintendo's Wii went on to trounce the PS3's Japanese sales is, sadly, not recorded.

That's not to say that Harrison would have had Sony build a console like the Wii. His career at Sony was all about software development - given input into the design of the PS3, he'd have wanted a console that was easier to develop games for and cheaper to buy, as well as being more open to extra input methods for social gaming, but he'd probably never have followed Nintendo's approach of making an underpowered console with no HD support.

Harrison's time at Sony is remembered for social software - but it also gave us many of the company's most beloved hardcore franchises, from Wipeout through to Killzone. Jenova Chen of thatgamecompany even credits Harrison with securing the three game deal that brought flow, Flower and Journey to PSN - showing an eye for the kind of quirky, left-field titles which had made the PS1 and PS2 so beloved of many gamers.

Nevertheless, by 2008, Harrison's time at Sony was done. As for his ambitions in social software, though, Harrison clearly felt that he could carry them out elsewhere. His first move away from Sony was to join Atari - a venerable gaming brand that had been in decline for years, but which seemed about to gain a new lease of life. Electronic Arts' former development boss David Gardner had joined as CEO, so Harrison's arrival was an impressive show of executive strength. The pair planned to turn Atari around, building a development powerhouse which would focus on online distribution and social gaming. A clear statement of intent came when SingStar creator Paulina Bozek also joined the company.

It wasn't to be. Neither Gardner nor Harrison lasted long at Atari - Harrison was there for a year, departing in May 2009, while Gardner stepped down that December. The problem was money. The hope was probably that by bringing in experienced executives and suggesting a radical new plan for Atari, the company would be able to raise capital for its new ventures - but the Atari brand was too stained by failure, and when Harrison left, the company announced that a number of projects were being cancelled due to a lack of funds. The dream had died.

Harrison soon re-emerged, however - pursuing much the same dream in a very different way. Along with Gardner and a couple of other industry heavyweights - former Criterion boss and current Unity chairman David Lau-Kee, and veteran games investor Paul Heydon - he founded a fund called London Venture Partners, aiming to raise money and pump it into new ventures in social, mobile and online gaming.

Everything went quiet for a while, as London Venture Partners raised funds for its investments - and then a flurry of investment announcements came in 2011. First up was Finnish developer Supercell, which creates browser-based games like online RPG Zombies Online. Others followed - LVP funded another Finnish developer, Grey Area, which focuses on location-based smartphone games, and PlayJam, a company which builds games for embedded chipsets in high-end TVs.

The fund was investing in areas outside of traditional console gaming that had the potential to become huge in future. Harrison told an audience at Games Invest 2010, which ran alongside that year's Eurogamer Expo, that "this is a fantastic time to start a company", but warned that "the older leaders of the old economy may not make the transition". From console evangelist, he'd become a prophet for the new digital economy - smartphones, tablets, browsers, connected TVs, and all the rest of it.

That might seem like a slightly worrying thing for core gamers wondering what Harrison will do at Microsoft. The question is which of Harrison's backgrounds Microsoft wants him to reprise in his new role. Do they want him to repeat his success at Sony, where he balanced pioneering social software with a track record of building third-party support and internal development studios? Or do they want him to focus on software and services that will let the Xbox 360 and its successor compete with the new wave of mobile, social and casual games?

The answer is probably a bit of both. Microsoft has had some social success with Kinect, but seems a bit unsure what to do with it next - and certainly not sure how to make core gamers warm to the peripheral. It's also got some exceptionally talented studios in Europe, most notably Rare and Lionhead, which have arguably not been living up to their full potential - and many in the industry would tell you that if anyone can turn that situation around, Phil Harrison probably can.

On the other hand, Microsoft does want to be ready to take on iOS and Android devices in the coming years - be that with the next Xbox, with Windows 8 or with Windows Phone 7. Which of those will be Harrison's priority, only Microsoft could tell you, but it's likely that both things are on his substantial to-do list.

Perhaps the biggest question, though, is whether Harrison will be able to make gamers warm to him as a Microsoft executive. He still bears the stain of the PS3 launch era, and reaction to his appointment at Microsoft was very mixed as a result. His hope, no doubt, will be that five years from now, when someone else comes to write a profile of him, 2005's 'target renders' and the awkwardness of the PS3 launch is just a footnote to greater achievements at Microsoft. Xbox fans, too, will hope that his work at Microsoft shines - even if it'll feel a little strange to them to be rooting for Phil Harrison. Sometimes the merry-go-round turns in very odd ways.