Peter Molyneux: Why I quit Microsoft, and why my new game will change the world

Did Milo's cancellation force his hand? What is his deepest regret? Plus, the issue of making promises you can't deliver. Molyneux in his first interview as an indie (again).

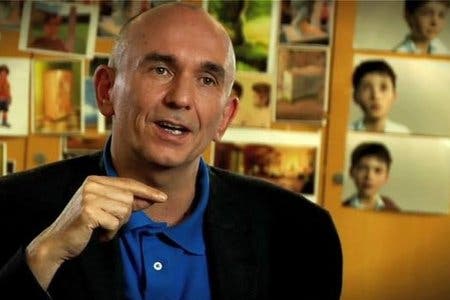

"How long have you got to talk?" I ask Peter Molyneux at the beginning of our Skype interview.

"I've got the rest of my life."

We in the video game press aren't used to this, and I admit that I'm thrown. We're used to 10-minute interview slots - timed to perfection by a watch-tapping publicist - that rarely result in anything useful.

My mini-rant complete, Molyneux tells me he hates it too.

"You've got to compress all of your passion, explaining the game, demoing the game and fielding questions into 10 minutes," he says behind a statue-still mugshot of himself snug neatly into our conversation window.

"Plus, they always in these events serve alcohol, which is the worst possible thing, because either you get a journalist who's hungover from the previous day without any sleep, or you get a journalist who's drunk and would much rather talk about how Chelsea aren't the football club they used to be."

The thing is, Peter Molyneux doesn't have to worry about any of this any more - well, Chelsea's form remains a going concern. He doesn't have to worry about explaining his game in hundreds of 10-minute demos back to back with time perhaps for a solitary drag of a cigarette sandwiched somewhere in between. And he doesn't have to worry about saying something that turns into a headline that gets him into trouble, because now there's no-one to tell him off. He's his own boss.

Last month Molyneux left Lionhead, the studio he founded 15 years ago, and Microsoft, the company he sold his studio to in 2006, to found Guildford-based start-up 22Cans. "I felt the time was right to pursue a new independent venture," he said in a statement provided by Microsoft. "I just felt compelled to become an indie developer again," he later wrote on Eurogamer's forum.

That announcement was only a glimpse at the true story behind his shock exit, one sculpted by his former corporate overlords. Now the unshackled Molyneux sits in his 22Cans office - just a stone's throw from Lionhead - we get a better, more revealing look.

Over the course of our wide-ranging interview we discuss the immediate (why he quit Microsoft to go it alone), the less immediate (why he's sort of inspired by Coronation Street) and the thorny (those high-profile broken promises). But perhaps most important of all, we discuss Peter Molyneux's next game, an experience he believes wholeheartedly will change the world. More hype from gaming's most passionate developer or the next big thing in entertainment? Read on, and you decide.

The first question has to be, why?

Peter Molyneux: Well, it's not an easy answer. It's a slightly complicated answer. Here I was at Microsoft and Lionhead, and it was very secure and comfortable. There was the Fable franchise, which is a great franchise. There were some wonderful people to work with. And Microsoft's a wonderful company. I was very comfortable.

Then, about 18 months ago, this sequence of strange things started happening. I started getting all these lifetime achievement awards and BAFTA fellowships, and gosh, who knows what else? I almost lined them up on the shelf, looked at them, and thought to myself, well, are these awards really for things I've done in the past? Do they represent the best I'm ever going to do? Or do they represent a challenge to what I am going to do?

"I just couldn't accept the best I am ever going to do in my life has already been done."

I got myself into this slightly obsessive state where I said to myself that I just couldn't accept the best I am ever going to do in my life has already been done. I've got to take the bit between the teeth and go out there and try and do something truly, truly great.

All this stuff came together, and I went to speak to Microsoft a few months ago. They were very understanding about it. And we agreed two things. The case I put was, the best a creative person can ever do is when there is a lot of risk and when there is a lot at stake. That's hard to do within a big corporation like Microsoft. Secondly, the type of people I would need to exploit all this new stuff would be slightly different from the type of people who were at Lionhead.

So, after a lot of talking, we agreed I would leave Microsoft and set up a new company. Of course, Microsoft was very keen to talk about a deal, but I didn't want to constrain any creative endeavours this new company would do with setting an early deal. That's what I did at Lionhead, and it really did end up constraining what you ended up doing.

I spoke to a couple of colleagues who weren't at Lionhead anymore. One was Peter Murphy, another was Tim Rance. We decided to found 22Cans.

Was there no scope to create something within the Microsoft corporate structure that would allow you to do what you wanted to do, perhaps bringing new people in?

Peter Molyneux: For sure. Absolutely. There was and they talked a lot about that. They were receptive to the ideas I had. But at Microsoft, there was nothing risky about it. And of course there are things Microsoft and Lionhead get involved with and there are things they don't get involved with. I really wanted to experiment and invent and create things that used all sorts of tech that's around at the moment, and that's semi-problematic for a big company like Microsoft. They're somewhat constrained by what they can and can't do.

"I really wanted to experiment and invent and create things that used all sorts of tech that's around at the moment, and that's semi-problematic for a big company like Microsoft."

It was just purely a personal feeling. And you've got to remember that my best work I've ever done, I think, has been when I've been an independent company. A motorcycle courier came, delivered a package to Lionhead in the early days, and he was just brilliant, and for some unknown reason, we employed him and he turned out to be an amazing bloke. It's those sort of policies you can't get past the HR of a massive corporation of 300,000 people.

In the last four weeks since we've been going, technology has moved on. That pace of change is very hard for a big company to keep up with, whereas a small company can shift and move. Draw Something is a perfect example. No-one would have thought OMGPOP would have been such a huge success. That's come about in the last eight weeks. Only a small company of incredibly smart people can be that nimble.

So, that left me in a position where I thought, well, my best work is always when I've got a small team of independent developers. The indie community I found incredibly enticing. I remember going on to the GDC Awards last year and the year before. They always start off with this video that says, f**k you triple-A developer. In a way, although that's obviously a bit of satire and comedy, they're right. For me, a lot of the really amazing things, the seeds of amazing experiences, are coming out of the small indie community. I've got my criticisms of the indie community, though. There are a lot of ideas but an awful lot of them never come to anything.

You put all that together, and it was me thinking, right, I'm going to go out and first of all find an incredible team. And I've got an amazing idea, and we're going to work on that idea.

Were you a little bored of Fable, perhaps?

Peter Molyneux: No, not really. The brilliant thing about Fable is it's got a flavour all to itself. There's this blend of humour and accessibility. It's a very realised world. In a way, I would love to see Fables go on and on and on, because it is a world rich enough to support that. You can see the amazing team there experimented with a lot of ideas, from dogs to one button combat to gosh knows what else. I wasn't bored with that at all. The Journey, there's nothing like it at all. I'm still consulting on it now, and I find that creatively very exciting.

I don't think at the moment Fable fully exploits all the exciting stuff that's happening in the world of computer entertainment. It's much easier to exploit that when you're a small company.

Were you maybe subconsciously motivated to leave by what happened with Milo & Kate?

Peter Molyneux: I was very disappointed Milo & Kate didn't go anywhere, I have to say. I thought it was an incredibly brave step. It was a very controversial step. It was something that was far more realised than the world ended up ever seeing. For me - and maybe The Journey has some of this - it was what a new input device like Kinect should exploit. It should give you something you've never seen or experienced before, and Milo was that.

As an experienced developer, you have to take the rough with the smooth. You can't expect every game you ever do to go that smoothly, and unfortunately it was one of those things that didn't end up coming out. I was disappointed. It always hurts. You always grieve things not being completed, especially as the world was so fascinated by it. It was definitely the most fascinating project I ever worked on. I just wonder whether or not, if Milo had come out, if it was still in development now and it came out now, the world is a little bit more ready for much broader entertainment. But two years ago - I know it doesn't sound very long ago - the world was different.

So, do you think that experience helped push you to make your decision?

Peter Molyneux: I'm sure it was there subconsciously. It wasn't a sulk. I can imagine - and maybe I'm one of those people - oh right, you won't go ahead with Milo, I'm off then. It wasn't like that at all. In business, you have to take the rough with the smooth. A decision's made, you have to live by that decision. You can beat yourself up or you can sulk as much as you like, but it's not going to do anything.

It was a personal, creative disappointment. I could see the sense in Milo not continuing. The point, which was very strongly made and which was very hard to defend against, was, if it was on the shelf in GameStop or GAME, where would it be? At that time it would have been next to Gears of War and I don't know how that features. I don't think the customers who Milo was aimed at would ever go into GameStop anyway. There were lots of arguments that were about more than just the experience itself.

But the fact you still ask about it is amazing. The Peter Molydeux character was born out of Milo because it was so contentious. In a way, it was designed to be that contentious. It was designed to make the world look at something and say, wow, what is this? You could do it about a green blob dancing on a purple planet. But you probably wouldn't get the same level of interest.

You've been going it alone for a month now. How's it been?

"I told Lionhead on the Wednesday 10th of March. I stood up. I like standing up and talking to people. I do. I do talk a lot when I talk to people. But on this occasion I stood up and I couldn't think what to say."

Peter Molyneux: It was kept very confidential for a long time. I told Lionhead on the Wednesday 10th of March. I stood up. I like standing up and talking to people. I do. I do talk a lot when I talk to people. But on this occasion I stood up and I couldn't think what to say.

I apologised and said they were brilliant people. I walked out of the office. I took the 275 steps from Lionhead to 22Cans. I sat down and the first thing I did was to clear my diary out of all the recurring meetings that are necessary when you are the head of a 200 person company within a corporation like Microsoft. That was the first cathartic thing, to realise well over half my time was spent not doing anything creative at all, but just simply helping to run a company. I felt incredibly guilty, but also incredibly excited.

Why did you feel guilty?

Peter Molyneux: It was almost 15 years. In a way you feel very parental about the company and you care for the people there and you worry about them. You can't help it. It's a bit like a divorce in a way. You may make sense, but at the end of the day you can't help feeling guilty. My main guilt was born out of the excitement I had. I can remember, I was sat down at 11 o'clock and I cleared my diary out, and I almost was giggling like a little schoolgirl with excitement about what would happen next.

The next thing I thought was, well, I can now do the things that were unimaginable to do when I was part of Lionhead and Microsoft. I can start trying to code again! I can talk to the press! I can say anything I want to the press! I haven't got this army of PR police people around me. That sense of freedom is incredible.

My first realisation was - and this was about half past 11 - I cleared out my diary at 11, installed Unity at a quarter past 11, typed some code by half past 11, and then my next realisation was, I'm going to have to find an amazing team. Really, that's been my obsession. Already that team is starting to come together.

We've got an interesting idea about the shape of the team we want. The thing is, if you want to do something truly amazing and brilliant, you and I could come up with 10 ideas which could probably change the world. Everyone comes up with 10 ideas. You look at the Molyjam thing, the number of ideas that were explored there. But, those ideas are utterly useless without amazingly brilliant people to implement them.

So we've been thinking about how to bring a team together to be that incredible and amazing and inventive. What we've settled on is we need to have about five people who are veterans. They're people like me, with my pedigree. People like Tim Rance, who's been the technical director at Lionhead, a technical director at EA, a technical director in the City of London. Someone like Peter Murphy, who's more on the business side. He started Camelot. He helped us at times at Lionhead. He started a lot of businesses and explored a lot of areas. He's fascinated about the world here.

We're mixing with those veterans, people who are experienced in the industry, who have made a game before, but, crucially, still have the passion to make something new. Maybe they're people like myself who think their best work is yet to come. Having about seven of those to mix with the five veterans.

And then lastly, the last five are just unbelievably passionate graduates who want to break into this industry, who perhaps haven't been given a chance but are bright and passionate. I'm hoping a few of those will apply to jobs@22Cans.com. We're trying to target some of the industry-experienced people and some of the young fresh talented people. And that adds up to 22.

Hence the name?

Peter Molyneux: Maybe hence the name. Or maybe it's 22 to make the name plausible.

Do you need a publisher for your new game? Or will you finance and publish it yourself? How's the money working here?

Peter Molyneux: Well, we are funded at the moment - not funded through a publisher. The thing is we're not going to make an app for iOS and want it to be in the top 1000 apps. That's not what we're doing here. What we're trying to do is make something that's truly a moment, truly a step change. That's our obsession. And for sure we're going to need a partner to help with that.

There are all sorts of reasons to get a partner. Money is one of them. We're lucky enough for that not to be the primary reason. Obviously more money is always better. You have to have funding.

Presumably Microsoft expressed its interest when you revealed your plan.

Peter Molyneux: Absolutely they have. But it would have been a mistake. I made this mistake with Lionhead. There was a deal signed with EA before the company was even formed. What that ended up doing was directing the first experience we made at Lionhead, which was Black & White, which was very successful and everything, but it did influence the way the company was formed.

I'm just so passionate about implementing this idea and getting it to a state where I can show it to people and it would be just absolutely fascinating. That's the best time to talk to people about any partnering.

"I actually have an almost physical love for Microsoft. I know people there incredibly well. I love their direction, their passion. They're definitely people we will talk to for sure."

I actually have an almost physical love for Microsoft. I know people there incredibly well. I love their direction, their passion. They're definitely people we will talk to for sure. I just don't want them to be the only people if you see what I mean.

So you're more interested in someone to help with, rather than dictate the creation of this game?

Peter Molyneux: Yeah. It's this simple. I could tell you what the idea is now, and you would be fascinated, intrigued and you'd look at me with a sideways glance perhaps. We'd go out of the room and you'd probably feel fairly excited. But, that excitement only lasts for a little while. It's not until you can get something a little bit more tangible, that you can touch and feel and understand, not through the words I tend to speak but through the experience itself, that you really can appreciate what we're trying to do.

My plan is to find a fantastic team, work on something that is more than just a few pieces of paper or what the triple-A industry calls pillars, which I think are ridiculous, so when I say, look, this is going to change the world and I say this is why, I can point to something and you can see it tangibly there. That's my idea.

Although I'm not going to talk about the idea, I will say there are so many ingredients that go to make up an amazing game now, and those ingredients just didn't exist even a few months ago. Whether you talk about new ways of input, or smartglass or motion control or the evolution of whatever consoles are going to be. There's the cloud, where can save your game to it and off it goes and you can go to your friend's house. But it's so much more than that! It can be so much more!

What I love about cloud computing - and this hasn't been explored yet - is that it allows for something that we as gamers haven't had since the start of gaming, and that is persistence. We don't have worlds or experiences that can continue and last for extended periods of time. We need to get rid of saved games.

So many times we in this industry make experiences for these small tiny little boxes of people. Now, you may say Call of Duty, the 15 or 20 million people who play, that's not a particularly small box. Well I think it is a small box. Call of Duty excludes so many people who just simply cannot play it because they're not good enough. The trouble is, I love the idea of connecting to people. I love the idea of connecting to my friends. The fact I have to filter those friends by their skill and by what they're able to do... There's an incredible opportunity there.

Why shouldn't we worship and celebrate people's differences? There are a variety of games in the real world that do that. So many times we make an experience to be, you start at the start and finish at the finish, and that's it. You move on to another one. But if you think of what you do in your life, your hobbies last an awfully long time. Imagine a game experience that was more like a hobby, a game experience you continued to play for weeks and weeks and months and months and years and years. I find that fascinating.

"Imagine a game experience that was more like a hobby, a game experience you continued to play for weeks and weeks and months and months and years and years. I find that fascinating."

There are a ton of these things that have really inspired me. And putting those things together and thinking of an experience that celebrates and exploits all those is very exciting. You know, if I talk about it much more I'll just end up telling you the idea!

The more you talk about it, the more I wonder if it's even a video game in the traditional sense at all. Can it be described in terms of traditional game genres, such as shooter or role-playing game?

Peter Molyneux: I've always been a little bit rebellious against those pigeonholes. Populous was the first example of that rebellion. And Theme Park - there was SimCity before it - but there was nothing that said, why don't we take something and make a simulation based around fun? So I've always experimented and played around with that.

But the genres we define at the moment are in crisis anyway. How can you even compare in the same breath Draw Something with Call of Duty? Where are your genres there?

I can guarantee it will be a game. It will be an experience. It will be something you may point at and say, I can understand why they're doing this and that.

You mentioned the idea that a game can change the world. Is that your ambition with this?

Peter Molyneux: Well, let's just think about this for one second. If I said to you, five years ago how many people are playing a game at this precise moment, you would have probably added up whatever the most successful thing at that time was. You would have probably added Halo numbers to DS numbers. You would have come up with a figure of two million or three million people playing.

Now, five years further on, how many people are playing a game at this precise period of time? It must be tens of millions, if you add in iOS, Facebook, XBLA, Android. Is it tens of millions? Is it hundreds of millions? Why should we stop that growth curve? Why couldn't we say computer games are played by everyone, like everyone watches TVs?

"Why can't everyone in the world be a gamer? When you've got devices, mobile phones and tablets that are powerful enough to challenge console gaming, it doesn't seem ridiculous. It doesn't seem bizarre."

I believe at this point in this industry we're just coming in to the equivalent of the television age. When televisions first went out to consumers there were a few million, and those millions rapidly turned into hundreds of millions. It wasn't only the wealthy enough people to afford a television. Over a period of a few decades that experience touched everybody in the world. And now it's almost unthinkable that people don't have a television. Why can't everyone in the world be a gamer? When you've got devices, mobile phones and tablets that are powerful enough to challenge console gaming, it doesn't seem ridiculous. It doesn't seem bizarre.

It took television quite a long time to get its head around providing entertainment for the world. I would love to have been in the kick off meeting for Coronation Street. Think about it for a second - what I'm trying to do is justify my madness a little bit. If I was sat opposite you before Coronation Street came out and I said, right, we're going to make a television programme, it's going to be the most successful television programme in the UK consistently for 40 years, it's going to be the number one or number two most-watched television programme, it's going to be on every single day of the week, your first question would be, that must be a hell of a story.

I would say to you, well, actually, there's no real story at all. It's the story of a street. What do you mean the story of a street? It was a completely different way of thinking of entertainment. Why should a story have an end? That's what Coronation Street said. Why shouldn't we make something like a hobby? People watch Coronation Street, it's their hobby. They think about it. It mulls in their mind when they're not watching it. They discuss it with their friends. And that moment in television history changed the world of entertainment. We had another one when we had reality TV. These moments happen and I think we're going to have similar moments, far more compressed, when we talk about computer entertainment. We're going to be making things that change and redefine the way we think about engaging with entertainment.

That's not saying I'm making Coronation Street the computer game by the way, just to make that absolutely clear. But you see what I mean. That's why I got so excited when I was at Lionhead. If you could think you could be there at the start of that revolution, where now entertainment is truly global, now it's not just the wealthy people who have slates and smartphones, they're filtering down to everybody. That's going to continue to happen. When you've got all this technology and all these ways of touching and using these devices, and bringing that together in one experience - that's really the reason we set up 22Cans. And then we change the world and everyone will be happy.

"That's not saying I'm making Coronation Street the computer game by the way, just to make that absolutely clear. But you see what I mean."

That sounds pretty ambitious for your first game there.

Peter Molyneux: It is. But you have to think like this. We're not setting up 22Cans just to make an iOS game. That's not the sole reason we're doing it. We're doing it because there's an enormous opportunity for change. And that change for someone like me and all the people who work here is incredibly exciting.

Have you established a timeframe for this?

Peter Molyneux: Yes. When you're an indie developer, the weeks you used to take to do something when you're a triple-A developer have to take days. I definitely hope to have something to talk about to the world within a few months. That will depend on any partners we have of course. I'd be disappointed if you didn't hear from me more in the oncoming months. I'd be very disappointed if we didn't have something pretty realised within a year.

Do you think people will be able to play your game this year?

Peter Molyneux: Oh, this year? You sneak that little thing in there at the end. I hope so. One of the things we are definitely going to do is involve a community in this experience before it's completed. I love the idea of what Minecraft and Markus did. I love listening to people's positive and negative points. This world today is very different to the world where we used to stick something in a box and put it on a shelf and the world didn't need to see it, touch it or experience it until it was absolutely finished. Those days have gone forever.

Designers and teams who make experiences have a digital relationship with the people who play. That digital relationship isn't one way. It isn't us pumping out content and the consumers just accepting it. It's a two-way street. Some people call it analytics and business intelligence. I think looking at the right data from consumers is an essential part of crafting an experience and listening to consumers and giving them a voice is an essential part of that. To do that you cannot afford to lock yourself away in a box, finish and then issue forth. I'm not giving you a time. But I am saying my motivation is to use the community to help refine the experience.

It doesn't sound like an Xbox 360, PlayStation 3 or console game. It sounds perhaps like a PC game. Have you even thought about platforms yet?

Peter Molyneux: I've got some thoughts about platforms. Platforms are popping up all the time. The last 10, 15 years have been unbelievably easy for triple-A developers knowing your platform and knowing it's not going to change. Talking about platform transitions happen every seven years - those days are gone forever. God knows what the world will come up with in terms of platforms in the next few years. Platforms are to do with peoples' ability to touch entertainment. Interactive TV - we haven't even started on that. We haven't even started on the true ability of what tablets and slates are. You have access to everything at the quality you feel most comfortable with all the time.

"I definitely wouldn't exclude the consoles. But I wouldn't just say it's a console game."

I'm not excluding consoles. If consoles are like the cinema, and if everything else, if Facebook and smartphones are like television, they can co-exist. I definitely wouldn't exclude the consoles. But I wouldn't just say it's a console game.

When our readers hear you talking about your new game, some will say they've heard you hyping your games before and things didn't turn out in the same way. Some may ask, is this just a repeat, or has something actually changed now? I wonder about the reaction of some who feel they've been burned in the past by what you've said.

Peter Molyneux: I totally understand that, and I totally see that's the case. The only thing I would say is those people being burned will motivate me to make a far, far better game. I thought the worst time was around Fable 1. That was the time when Lionhead was going from a small company into a big company, and that's when that thing about me making a lot of promises that don't get delivered on came.

I wrote an open letter apologising for making those promises and I stand by everything that letter says. Since then I try and say to people, when they read something about me, this is not me being a press person, this is me truly looking at myself in the mirror and saying, what am I trying to create here? Am I trying to create something that is going to be just another game, or am I trying to say we're creating something that is going to change the world?

"Am I trying to create something that is going to be just another game, or am I trying to say we're creating something that is going to change the world?"

By saying change the world, there are games out there that have already done that. A lot of people in the industry would say, that would be Call of Duty, wouldn't it? I think it has changed the world a little bit. So do I think CityVille has. FarmVille has touched so many people. Same with Draw Something.

My definition of changing the world is connecting people together, of there being more of a persistent experience, of there being the ability of different people with different interests and different skills, playing and contributing and adding together.

If I did all of those things, and I did them well and it was well crafted with this amazing team I've got, then it would change the world. That's what my definition is. It's neatly packaged up by me saying that I'm going to make a game to change the world - and I'm sure you're going to use that as the headline. But my caveat on that is, I just don't want to make something that's like another game.

A lot of people have said why didn't you make Dungeon Keeper 4, why didn't you make Black & White 3, why didn't you make Populous 4? I don't want to make a game like I've made before or necessarily like any other games. There will be elements that will be like things I suppose, but not the main experience. So, I can understand people getting annoyed about promising. I think people get most annoyed when I talk about features I can't show, and I promise a feature people get excited about. That's the mistake I'm going to really try to avoid making.

Now you look back at your career at Lionhead - the company you founded - what's your highlight?

Peter Molyneux: It's amazing to bring a team together. That's the most incredible experience. Lionhead was started with four people and it grew into a company that was at its peak 300 people. Starting with nothing and then ending up with a game like Black & White is an incredible journey. Just that amazing experience of working with people who are 20 times smarter than you are is brilliant. I loved that. For a long time that was my entire existence.

Working with people like Simon and Dene (Carter) and Mark Healey and Alex Evans, who founded Media Molecule, seeing all those people go out and establish little companies of their own that turned into big companies, that was an amazing experience as well. I worry about them. Simon and Dene, I worry about them. I lose sleep thinking, are they all right? I love the fact they have gone out and been brave enough to do what they're going to do. That's fantastic.

I loved selling Lionhead to Microsoft and experiencing what the corporate world's like. I found that fascinating and intriguing. Everything from the incredible Microsoft Research through to fully understanding how marketing and publishing really works. I found that utterly fascinating. There have been so many high points, it's very hard to pick out a single one.

What about games? Is there a game you created while at Lionhead you're most proud of, or is that too abstract a question to answer?

Peter Molyneux: It's not an abstract question but it is a difficult one to answer. I find making a game is like being a parent. You feel very protective about the games you do, you feel very proud about them, and you love them. Just like a parent, it's very hard to pick a favourite child.

I think I love features more. I loved the dog in Fable 2. That was a moment where we realised gaming experiences aren't just about the weapon you've got, that you can give something else to players. I loved the creature in Black & White. I loved the world in Black & White. I loved the theme of The Movies, but I think we made a terrible mistake with The Movies.

Why do you feel that?

Peter Molyneux: I thought the subject matter was really good. The world is still obsessed about Hollywood. But I thought the game was too frantic. There were too many things to think about and do all the time. If we'd just made it a lot simpler, it could have been a lot more successful. If we'd taken out half the features it would have been a far better game.

But the dog from Fable 2 stands out for you?

Peter Molyneux: Yeah. It was a great journey to implement that feature. The emotional link people had with their dog - I've still got letters from people who said, I love my dog and when it dies these terrible things happen. That's how you measure success.

Conversely then, looking back at your time at Lionhead, what is your deepest regret?

Peter Molyneux: I take this as a personal failure. And it is a personal failure. Not being persuasive enough that Fable 3 needed more time. That's purely and utterly my fault. It's me not being clear enough about it. The subject matter of Fable 3 was really good. Becoming a king was a good centre point for a game. It's a shame we didn't find more time.

Why weren't you afforded more time for Fable 3?

Peter Molyneux: It's probably better if I don't go into the details of that. As a creative director you always have to be clear about why you need time. Any publisher in my experience over the years, they don't want to give you more time. Of course they don't, because it means more money. But they equally don't want you to make a mistake with the product.

It's very difficult for publishers to actually appreciate why more time is needed and what the business case for more time is. That's the responsibility of the director who's in charge of that developer. That's me - to explain that and make that clear.

It must have been interesting physically leaving, given your inside knowledge of Microsoft. I've heard horror stories of staff being escorted off of premises and computers wiped. What was the experience like for you?

Peter Molyneux: I don't know. I'm still on that journey. I come to some form of conclusion I guess this evening when I've got my leaving drinks.

Are you expecting a big send off?

Peter Molyneux: I don't know what I'm expecting. I'm slightly nervous about it. So I don't know. I could be alone in a pub drinking a pint of bitter. Come along!

Where is it?

Peter Molyneux: It's in a pub called The Stoke in Guildford. Feel free to put that in the article by the way.

I'm not sure you'd appreciate being descended upon by thousands of Fable fans.

Peter Molyneux: I'm not saying I'm going to buy everyone a drink! Let's be clear about that...