Growing Paynes: How Remedy's Hero Went Rockstar in Max Payne 3

From a NY noir to the liver of a French goose.

This article contains plot spoilers and is best read once you've finished Max Payne 3.

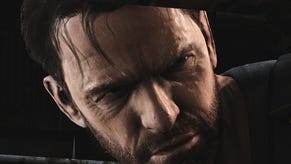

It was a strange day when Rockstar's take on Max Payne emerged as a fat bald dude with a bad temper. I remember blowing air into my cheeks and making a worried parp noise. No one likes change.

I grew in faith, sure, but this remained a far cry from the slick hero who once jumped sideways through Brooklyn in a familiar leather jacket and bad tie combo. As it turned out, however, Fat Max™ managed to fill those initial doubts full of bullets the second he entered the room.

Rockstar's homebrew Max Payne 3 drops the eccentricity of Remedy's games, and the 'always on' gravitas and lack of self-knowledge certainly robs the game of many elements I loved the first time round. There are no non-combat sections that have the wilful insanity of Mona's funhouse, dream sequences heavy on baby blood trails aren't present and you'll never ever protect a gangster who's trussed up in the garb of Captain Baseball Bat boy. Max Payne 3's fourth wall is never even scraped with a stray bullet, let alone broken.

What all this is replaced by are Rockstar's overblown and super-serious cinematic leanings - long cut-scenes, action shots borrowed directly from the likes of Bad Boys and True Lies, and a drink-fuelled opening so close to Apocalypse Now that Max might as well say, "Sao Paulo. Shit, I'm still in Sao Paulo." Max Payne 3's narrative is a slow-burn and over-populated affair, but the character arc at its centre is fascinating.

On this occasion the Houser Hollywood affectation runs deeper than the way the game looks and plays. Away from a wildly swerving plot of crosses, double-crosses, swiftly introduced villains and almost two thousand bloody deaths, the game's foundations are the changes we see in Max's character himself. In other games the hero is a one-note triumph machine tangled in other people's problems, but here we play as someone dealing with personal issues as the game progresses. The Brazilian funhouse is a linear sequence of scares, just like all the others, but the character making his way through suddenly seems a real one.

It's cinematic, but not just in the way it's a Michael Mann love-in and the snazzy way cut-scenes are framed and edited. Max Payne 3 really is Screenwriting 101 - Rockstar may mess with the timeline in flashbacks but the way it mirrors the Hollywood hero's journey is almost uncanny. He goes from a desperate and lonely alcoholic in New York, to a fish out of water in Brazil, to an avenging angel with a deathwish - and the state of his hair, face fuzz and gut throughout is a sign of his passage.

On top of this, supporting characters cleverly highlight Payne's situation - whether it be the retired US cop with a happy marriage and a Christian charity mission in the slums, or Passos' end-game familial situation. Max Payne 3 makes you think beyond what you're explicitly told. Late on, when you're given the choice to pull the trigger on an unarmed man and you refrain (getting a rare grab-bag of Achievement points), you're slyly nudged into colluding with Payne's evolving mindset. It makes no difference to the game as it rolls on, but minds are broadened on both sides of your flat-screen.

The Fat Max story also picks up the baton neatly from Remedy and The Fall of Max Payne - a game that kills off every member of the Max Payne supporting cast (unless you play through again on Hard). After the Valkyr and Cleaner massacres you'd hardly find Payne back on the beat - it's far more real to find him a confused, broken and desperate man still blaming himself for the loss of his wife and daughter. It's logical that he'd become a gun-for-hire in the private security field, a million miles away from his old life. It defies video-game sequel logic, but for the character it makes sense.

"The final levels of Max Payne 3 are one part Taxi Driver and two parts Die Hard - the writing crackles, buildings crumble, bad guys pay and everything explodes."

Importantly, however, the link to Remedy's games is not entirely broken. I'd argue that the three flashback levels to Max's past life in NY's Hoboken are the best of the game, but it's their sparing use that doubles down their role as fan-pleasers. It's like Rockstar playing a few old hits for the fans while touring a new album. Gravestones of deceased friends and enemies, a brief and understandably inconclusive mention of Mona, Captain Baseball Bat Boy on the television - there are underlying efforts to show that we're still in the same world even if the likes of the Illuminati don't get a namecheck. Even the brand of whisky Max slugs is Kong - the same one advertised on the underground in the original Max Payne, and available in Lupino's hotel in the second.

Serenading it all, meanwhile, are those same sad piano chords that serenaded our rain-sodden murders back in the Remedy days. Whether in sunny Brazil or the frozen streets of New York, the same brilliant streak of maudlin menu music underlines that we're very much back in the world of Max Payne.

Fat Max, however, is what takes these playable, tight and stylised trappings and then twists them into something that can grow beyond a one-off Rockstar reboot. The alcohol-fuzzed soul-searching that makes up much of the game has an amazing pay-off: Payne the vengeful force of nature. The feeling of depressurisation as Max releases his inner badass is amazing. When Payne shaves off his hair and starts looking like Bruce Willis, what's going to happen next is writ large in spent bullet casings and blood. The final levels of Max Payne 3 are one part Taxi Driver and two parts Die Hard - the writing crackles, buildings crumble, bad guys pay and everything explodes.

Payne isn't a faceless action cipher like Gordon Freeman or Master Chief, nor is he a genero-lunk like Marcus Fenix; he's a guy that runs deep. Look beyond the chaos he leaves in his wake, and you see that Max Payne is one of the greatest video game heroes we have. Long may his Bullet Time continue.