Board Games Are Back

Our heritage is catching up with us.

I want to begin by telling you that board games have grown up but, actually, board games have been growing up for a while now. They've started to carry a dignity and a sense of style that's turning the head of many a video gamer. It's like they went away to boarding school young and geeky, and now they've returned as buff and hunky adults, all strut and swagger. Sales are rising year on year, while the hobby's biggest convention (Spiel, in Essen, Germany) now attracts more attendees than E3 and PAX combined. Most importantly, more and more video gamers are buying board games and if you're not yet one of them, let me tell you why you should be.

First of all, I'm not talking about the dreary, dry, musty, interminable agonies that are Scrabble or Ludo or Trivial Pursuit. Those were never games to begin with - they were only tests of your patience, exercises in repetition. I'm talking about proper games, games of grand strategy and espionage, of deception and teamwork and battling against the clock. Games where civilisations fall and spaceships soar and people with names like Durlak the Unshaven are busy smashing goblins noses out through the back of their heads.

Does that sound more like the kind of excitement you demand? It's no surprise that video gamers are starting to champion them as much as they might any new platform or next generation console, coming together again and again to enjoy a wealth of new and original gaming experiences.

Why? Well, chances are you already play games on more than one platform because you enjoy the variety this presents. Maybe you flit between a PC and an Xbox, or an iPad and a phone, or all of these and more for all the different things they offer. All you need do is imagine your tabletop as your newest (and most inexpensive) piece of gaming hardware, capable of showcasing an enormous variety of games quite unlike anything you've ever played before, and consider these three points:

Board games can make us the focus of the game, not what we're watching on a screen:

The last console generation saw an enormous shift toward multiplayer gaming online and away from players sitting together, pads in hand, around the same TV. Video gamers are picking up board games to get back to playing with their friends again. "People seek social interaction, just look at the social network phenomenon," explains multi-award winning board game designer Antoine Bauza. "Board games are a strong social interaction vector, and a cheap way for people to rediscover the pleasure of playing together." The internet may offer all manner of gaming wonders, but for many it has removed this pleasure of playing together, separating us and mixing us with strangers who are as likely to be hostile as they are decent.

But even beyond this, a great many board games are not just played with other people sat around a table, they're all very much about the fact that a group of people sat together creates a completely different dynamic to gaming online. Many modern board games don't just know this, but exploit it repeatedly and ruthlessly, forcing players to negotiate, to bluff, to deceive or even to depend on one another, all natural human interactions that even the finest gaming AI fails to simulate satisfactorily.

"Board games are more interactive on this direct, human level," says filmmaker Lorien Green, director of the gaming documentary Going Cardboard. "They indulge these person-to-person interactions. You're reading body language, and seeing the little twitches or facial expressions that make the experience much richer." Richer and much more personal too, as it'll likely be your friends you're trying to lie to as you look them in the eye, and they may be able to read you like a book. We're complicated creatures, and a well-designed board game will try to exploit this.

Board games benefit from a diversity of design and creative freedom:

There's a glorious, glittering galaxy of board games out there just waiting to be tried, showcasing a thousand different ideas, all because designing and developing a board game couldn't be much easier. Unlike video game development, which is technically demanding and saddled with publisher constraints and genre expectations, all a board game designer needs is an idea, some card and a pair of scissors and they're already on their way to making a prototype.

"Anyone with a great idea for a game stands a chance of seeing that game published," says Green. "[Going Cardboard] presents several individuals who took different approaches to make this happen, from being an in-house designer to a self-publisher. It's sort of a wild west frontier, where land is there for the taking." More than a few designers have secured a publishing deal with nothing more than a well-tested carboard mockup that, at its heart, demonstrated a great concept, and Kickstarter has been launching board games (such as the megahit Eminent Domain) long before we were getting excited about its video game projects.

Think of the world of board games as an enormous indie games scene where everyone can develop their dream game, even the crazy one about running a spaceship in real time or slipping a balaclava over your head and declaring yourself a terrorist, where most games aren't rushed to retail under publisher pressure, and where originality and quality really can shine through. It may sound like a fantasy, but that's the reality.

Board games have inspired, and are now inspired by, video games:

Video gamers who take up board gaming find themselves in comfortable, familiar territory. Video games have always owed an enormous, incalculable debt to their tabletop progenitors, who have been bleeding their influence into them for decades. Sid Meier's Civilization was directly inspired by the '80s board game of the same name, Microsoft's Close Combat series grew from the popular hex wargame Advanced Squad Leader and the Mechwarrior, Blood Bowl and Europa Universalis series are just some of the many that were born of cardboard. Anything with RPG-style mechanics can draw a line of influence back through Dungeons & Dragons, past the miniatures game Chainmail and all the way to H. G. Wells' wargame development diary Little Wars, where the author experimented with ways to model combat as a game.

But now the influence is felt in both directions, as board game designers are taking all kinds of cues from video games, from the Pipe Mania-inspired real-time ship building in Galaxy Trucker to the Master of Orion-style space opera that is Twilight Imperium. And given this crossover, it's not so surprising that more than a few board games have been adapted as video games or iOS apps, allowing gamers to crowd around an iPad to play games like Ghost Stories, or enjoy Memoir '44 against a world's worth of opponents via Steam. The line between board games and video games is beginning to blur a little.

A rolling start

If you now fancy dipping your toes into the cardboard but don't want to dive into anything too deep, then you might want to start with a digital incarnation of a tried and trusted game. "There are the big three default gateway games," says Green. "Settlers of Catan, Carcassonne, and Ticket to Ride. All three of those can be accessed through electronic platforms now like Xbox and mobile devices."

"You've got to give Settlers of Catan a go," insists Michael Fox, a board game designer and creator of the popular British gaming podcast The Little Metal Dog Show. "It's the grandaddy of games and while there's plenty out there that have superseded it, everyone should play it at least once."

Selling over twenty-five million units worldwide, Wired dubbed this game of trading and construction a "Monopoly-killer." Catan is apparently about collecting different resources and turning them into roads and towns, which allow you to expand your influence and collect more resources. But really Catan is all about negotiation, or what many people call arguing. Players inevitably lack the resources they need to expand and, because the game features virtually no direct conflict, they're forced to trade with one another, broker deals, make promises and swear blind to you that if you hand something over to them they won't promptly win the game.

The forward-thinking Eurogamer reviewed Catan on the Xbox here and it will cost you 800 points on Xbox Live, but is just $5 on iTunes. A real copy will set you back £25-30 and an array of expansions add all sorts of features.

In Carcassonne, players construct a landscape together, tile-by-tile, while trying to lay claim to the partial cities and roads on these tiles. But claiming a feature does nothing, it's completing it that scores points, and trouble soon surfaces as other players try to make their roads or cities join with yours and get a share in your scoring, or build around your features and try to hem you in.

Half the game is plotting, half the game is improvisation and, as the endgame approaches, half the game is other players following the manual's coy instruction that they should work together to "advise" you where to put your next tile, particularly embittered players sometimes suggesting locations that are not within the spirit of the game.

Carcassonne will also cost you 800 points on Xbox Live and, just like its real-life cousin, can be bolstered by a bunch of add-ons. It's £7 through iTunes and you can expect to pay £14-20 for the real thing. Oh, and the Xbox version is reviewed here.

Ticket to Ride is all about completing rail links between cities before your rivals can. Claiming any route scores you points, but every player is also chasing specific, secret routes that will grant them a huge bonus if they're successful while, of course, trying to not to be cut off by some other jerk. Know your routes well, and you might just be able to deduce another player's loco-motives.

Funnily enough, it's also 800 points for the Xbox version and is likely to liberate £5 from your wallet if you choose it in the iTunes store. The glossy real-life version sells for a less modest £30-40.

It's time to take stock

But if you're really serious about bringing home a smart, sexy, stimulating board game, you'd do well to try one of these in-print, in demand titles:

Cosmic Encounter is a vibrant and vicious little thing that showcases a lot of what boardgames do best. Players attack one another with fleets of spaceships using rules that are almost pitifully simple, but every single player is given one of the game's dozens of unique alien races, each of which has some game-bending special ability that interferes with the rules. They might be able to reverse the outcome of a battle, steal things from other players or simply hijack someone else's success.

It's not just every game of Cosmic Encounter that's completely different - it's every turn. Players forge and sunder alliances, constantly promise that they will or won't use their special ability when the opportunity presents itself, and wait for the right moment to plant a dagger in an ally's back. It's endlessly, endlessly varied, nothing about its rules and instead all about the personalities of the players and the kind of tricks they're likely to pull. The base set is usually £40-50 and there are several cheap expansions that contain even more absurd alien races.

For the same price, and for those willing to bury themselves in something much deeper and much longer, there's the chance to play A Game of Thrones on your dinner table. It's best described as a more elaborate version of the age old board game Risk and, just like the books its based on, this is equal parts war, diplomacy and disaster.

Each player takes control of one of the books' great houses, leading them to war with their rivals, jockeying for power in the courts of the land and occasionally, grudgingly pledging their commitment to the defense of the realm. A game could take you three to six hours, perhaps even longer, and this is the sort of thing players set aside whole evenings, even days for.

Finally, "Everyone should try Dominion at least once," says Fox. "It shows that even though games have been around for millennia, there's always something new out there." He's right, because Dominion is just three years old and nothing more than a game of cards, but its incredibly simple, almost insultingly smart deck-building mechanic has already influenced many other games designers.

Unlike a collectible card game like Magic: The Gathering, Dominion is not about combat, nor is it about turning up with a pocketful of personally chosen cards. In Dominion, players start from scratch, with just a few cards that represent money, and play these to buy more cards from a central pool. Every card has either some value, some special power or is simply worth victory points and, once each is bought, it goes into a players collection, is eventually shuffled and pops up again later.

A canny player will buy cards with powers that allow them to buy more cards, or to perform more actions in their turn, trying to transform their turn into a cascade of actions, a domino effect where they play cards that trigger more and more cards in turn, but cards worth victory points are mostly useless and, though necessary to win, adding these to your deck only clogs that precise, efficient clockwork you've been carefully engineering.

Dominion is somewhere between puzzle-solving and engineering, and is both enormously popular, critically-acclaimed and very expandable. Off the shelf, it'll cost you £20-30. I wouldn't recommend its unofficial iPad incarnation because I believe it lacks a little clarity, but nevertheless it's free if you want it.

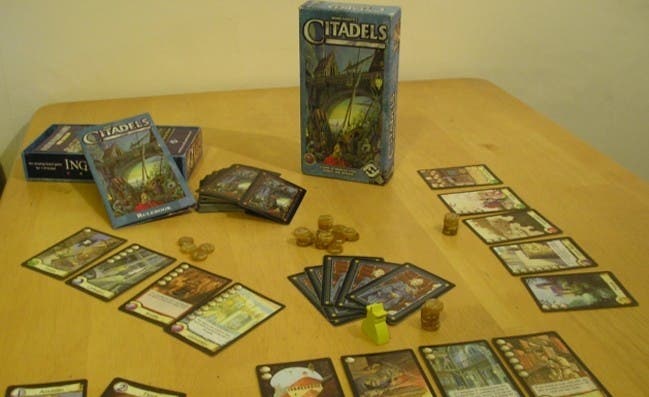

If this still isn't enough for you, then we have a lot more recommendations on Shut Up & Sit Down the show and site that fellow journalist Quintin Smith and I run. You can also raid the archives at BoardGameGeek and browse their list of top-rated games and you'll surely find something to your taste, perhaps the excellent Space Alert, Citadels, Bang!, 7 Wonders, Agricola or Puerto Rico. What're you waiting for? It's your turn.