Saturday Soapbox: Yearning Japanese

Lamenting the death of the import scene.

A little over a fortnight ago, I bought Anarchy Reigns from an online retailer; this week I downloaded New Super Mario Bros. 2 from the eShop on my Japanese 3DS. In the past, importing games of this stature was a no-brainer for me, but on both occasions I hesitated before taking the plunge. It seems many others have been equally reluctant.

I can count the people I know that own both games on one finger. These games are rarely discussed, assessed and dissected in excitable tones among small but enthusiastically vocal groups on forums any more. It's a recent development, and one that I find incredibly sad, because a few years back, the import scene was thriving. It was an exciting movement to be a part of, and now it's utterly moribund.

For some, the allure of what were then termed "grey imports" began in the 16-bit era. Through a mixture of impatience at delays and compromised PAL versions that arrived with horrid black borders or ran in 50Hz, SNES owners in particular would order games from retailers advertising in the back of magazines, encouraged by rave reviews of thrilling new Japanese titles in the likes of Super Play. For others, the Saturn years proved a rich source of shooters not available in western territories. My first import was for the GameCube, the advent of Datel's Freeloader allowing me to get my hands on Japanese and American games long before their European release to play on my PAL console.

It was 2002. A glowing appraisal of Nintendo's bizarre, bucolic life sim Animal Crossing in NGC magazine was enough to prompt a visit to the independent retailer down the road from the criminal law firm where I worked. I soon began to frequent this store with its collection of ancient arcade machines, retro magazines on the counter and faintly musty smell. But imports were expensive and it'd often be a couple of weeks after a game's US or Japanese release before the shop would have it.

By a year later, with broadband adoption on the rise, I was spending more and more time on the internet, chatting with like-minded importophiles on forums, who, annoyingly, were getting their games before I was. With their assistance I started shopping with online retailers. Getting Resident Evil 4 just 48 hours after its US release was a particularly notable moment, not least because thanks to shipping costs and import duties it cost me £75. It's one of very few games I'd consider to be worth every penny of that outlay.

After a while I found myself sticking to a trio of reliable, good value sites. For the most part I'd stick with English-language US releases from Canadian site Videogamesplus and I'd use Play-Asia or YesAsia for Japanese imports. The latter was more expensive but a little quicker, and that made all the difference, though I soon found myself taking advantage of the former's courier services to get my fix that much sooner. I was hooked.

My hunger for imports wasn't so much about that innate human desire to be first, but to be part of that initial conversation. I found I was enjoying that as much as the games themselves. The chatter was longest and loudest around brand new releases, and if you weren't involved in that, you felt you were missing out. It was like a secret society, but without the passwords and special handshakes.

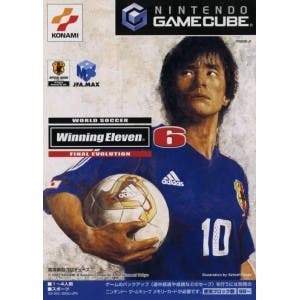

There were other benefits to importing, too: I still count the GameCube's tiny Japanese boxes with their cardboard slipcases among my ten favourite gaming-related things, and the boxart was often superior. The Japanese cover for Perfect Dark and the US cover of Ico compared with its eastern cousin are two strong cases in point.

Talking of Ueda's melancholic gem, by the time of its release I'd started playing catch-up with the PS2's wide range of idiosyncratic imports, which by now were available on the cheap. A clumsy workaround called SwapDisk (which asked you to wedge a tiny piece of plastic into the disc tray to stop it spinning so you could insert the game after the SwapDisk itself had acted as the passthrough) was my key to the kingdom, and I gorged on the likes of Gitaroo Man and Katamari Damacy.

Perhaps the most prolific period, though, was around the release of the original DS. While the console laboured in Europe after a reasonably solid launch, the boast of 'new ways to play games' ringing a little hollow, Japan was witnessing the likes of Daigasso! Band Bros, Slide Adventure: MAGKID and Electroplankton, weird and wonderful titles that really did feel properly, thrillingly new.

As I recall, the pound at the time was strong, and I was paying no more than £25 tops for brilliantly barmy point-and-click adventures about spiky-haired lawyers and rhythm-action classics about troupes of male cheerleaders dancing to save the world. Sure, some were clearly getting hold of these games via illegal means, as the R4 card and various alternatives flooded the market, but it was great to have more and more people joining in the conversation. Even so, this burgeoning movement somehow retained a sense of exclusivity. It was still a niche, but it was widening.

By now I was trying to spread the word even further. I'd join up to new forums, excitedly babbling about the latest imports that you really must buy immediately. My posts were getting longer, and more review-like, and so I set up my own fansite in a - possibly slightly arrogant - attempt to win more converts to the import cause. I was one of a few go-to guys for crucial import info, advising on software, hardware, websites and delivery times. I was delighted when people thanked me for recommending Phoenix Wright or Ouendan or Rhythm Tengoku. One of my proudest moments saw me convince three people to import a Famicom Micro in a single day.

It wasn't to last, of course. Some publishers were aware that the burgeoning import scene was costing them not-insignificant revenue. Things came to a head when importer Lik-Sang were forced to close, with Sony having issued legal action against the firm for the audacity to offer their customers the opportunity to import Japanese PSPs, some nine months ahead of the console's EU release. The likes of Play-Asia suddenly refused to ship Sony goods to EU countries.

By the time the Wii and PS3 arrived, the landscape had drastically changed. Region-locking was a self-afflicted curse for Nintendo's machine, forcing the dedicated to import a console that couldn't play games from their own region. In truth, Japan had very little the west wasn't about to receive as Nintendo finally bucked its ideas up and began to aim for roughly simultaneous worldwide launches. The localisation process was becoming more efficient, while Nintendo of Europe seemed increasingly determined to atone for past sins, releasing games before their US bow or even translating games that would never arrive stateside. Datel struggled in vain to make another Freeloader and duly released one that an update from Nintendo promptly rendered entirely useless.

Quite apart from the issue of region-locking and the clampdown on Sony hardware and software, the waves of recession were just beginning to break and the yen was strengthening against the pound and the dollar. The prices, so tempting for those with disposable income to spare in 2005, were steadily rising. These days, 3DS titles cost around £45 before postage and fees, with customs becoming noticeably more vigilant about charging duty on games. Even region-free consoles like the PS3 have been affected; importing was becoming a rare luxury for the cash-rich, and there weren't so many of those around anymore.

The rise of iOS and the currently blossoming indie scene on PC has undoubtedly played a part, too. Here, you can enjoy quirky, original games, and get them much quicker and cheaper. Meanwhile, the Japanese industry has grown more insular, focussing either on games specifically to please eastern audiences (often text-heavy affairs that tend to discourage non-Japanese speakers) while the bigger publishers have been actively courting western players and losing a little of their identity in the process. There are exceptions, like Anarchy Reigns, thoughtfully translated into English for its Japanese release by the developer for the sake of those unwilling to wait until March. Yet at the equivalent of $100 it's out of the range of all but the most dedicated enthusiast.

Much as I love discovering the weirder stuff on iOS and PC, it's not quite the same. That extra investment - not just a financial one, but the whole process of ordering and receiving your package - gave you a greater sense of personal connection with your purchase. We gamers do love our rituals, after all, and I genuinely miss that excitement of hearing a package hit the hall carpet, quickly ripping open the Jiffy envelope and unwrapping the cellophane to reach the treasure underneath. Hitting 'buy app' might be a hell of a lot more convenient, but there's something disconcertingly impersonal about it.

Quite apart from that, the fractured nature of the industry - and of iOS in particular - means that everyone's playing something different. Outside the occasional phenomenon like New Star Soccer, or the AAA biggies on console, the conversation is more fragmented than ever. The secret society has disbanded, the members have gone their separate ways, and this glorious niche, an unforgettable part of my gaming life and of the medium's history, has been all but lost to the inexorable march of progress.