The Medal of Honor Tomahawk

When following "a dotted line to real world events" stops being offensive and gets scary.

(Editor's note: Since we published this report, EA has pulled the Medal of Honor tomahawk promotion and issued a response to Eurogamer.)

As a games journalist growing up in England during the rise of the internet and social media, I've never been terribly conscious of the vast, vast expanse of Atlantic Ocean that separates me from the many people I know and like in the USA. I speak to them all the time online and I even get to see them pretty frequently thanks to shows like E3, GDC and Gamescom that bring us all together in the same place. So it's remarkably easy for me to forget that, while we speak the same language, the USA is actually a very foreign country.

I do tend to notice it occasionally in video games though. One of my favourite examples in recent years was the original Gears of War. In the US, nothing seemed amiss. Reviewers noted that it was "a bit light on story" but reflected on how the game offered "a sweet introduction to the world of Sera and to Marcus, just enough to pique our interest". Meanwhile, over in the UK, we honestly thought the game was some sort of brilliant parody. I mean, the marines have shoulders like the back end of a horse and say things like, "That smells nasty. What are these guys made of, shit?"

It arguably ended up working in the series' favour, giving the game cult appeal among snobs like me who might otherwise be expected to overlook it (which is handy, because that meant we got to savour some sparkling level design and brilliant ideas like Active Reload), and perhaps the writers started playing up to it a little. After all, it's hard to imagine that even cultural differences could account for somebody with a straight face, busy writing Gears of War 2's script, to reach for inspiration and discover "They're using a giant worm!"

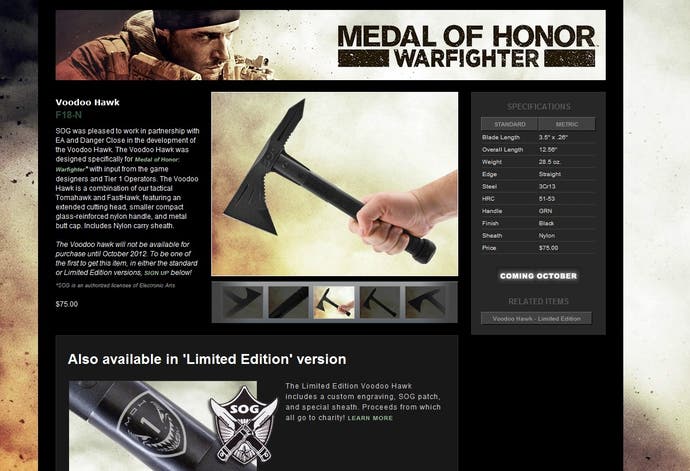

The latest example of the cultural disconnect I've encountered, however, is one of the most bizarre things I've ever read. As explained in Ryan Smith's Gameological Society editorial, EA is partnering with real-world weapons manufacturers not only to make sure that the guns in Medal of Honor: Warfighter are authentic but to make real-world weapons based on the game. I'm putting all this stuff in italics to emphasise how much it doesn't compute to my middle-class British liberal brain. Look! Here's a f***ing Medal of Honor tomahawk!

How did I miss this happening? Well, it turns out we did report on it when it was announced, but we missed a couple of details. Having gone back and dug up the press release, issued on 13th June, I can see why. "EA Launches Project Honor Initiative To Benefit The Families Of Fallen Special Operations Warriors" is the headline, and while it does talk about EA's partnership with "elite weapon and gear manufacturers", it mostly concerns itself with the way they will be giving money to charities that support real-world soldiers.

Fair enough, I guess - it's a video game about war, and it helps pay for the families of people who died in wars to have a slightly better standard of life. Obviously it's all phrased in the most nauseatingly mawkish language imaginable, but anyone who has ever listened to a politician refer to his or her armed forces is used to that, and the unique way America regards and salutes its military institutions wherever possible is one cultural signifier that is at least transparent to most of the rest of the world.

This is the special bit, though: "In addition to this, select partners have signed up to create and sell exclusive Medal of Honor themed merchandise and donate 100% of the proceeds of their sales to the Navy SEAL Foundation, the Special Operations Warrior Foundation and other charities." I have taken the liberty of emphasising the word 'merchandise' because I want to draw attention to the fact they mean things like real gun attachments and tomahawks.

The wording there makes it seem like EA's reluctant to shout loudly about the specifics of this arrangement, but it turns out nobody's even batting an eyelid about this stuff over in Medal of Honor land. Executive producer Greg Goodrich is all over the official site writing about partnerships with people like McMillen Group (motto: "Shoot to win"), who make sniper rifles and stuff like that, or SureFire, who make high-capacity magazines for M4 variants. "Here is a photo of me performing a full auto mag dump last Friday with a SureFire suppressed HK MP7A1," he writes. "If you can't get your hands on a select fire suppressed submachine gun head over to the SureFire website and pick yourself up the incredible 800 lumen UB3T Invictus™ Ultra-High Variable-Output LED flashlight and light someone up!" Woo?

Ryan Smith makes a bunch of interesting points in his editorial. One is that he grew up with 8-bit shooters like Ikari Warriors and Contra, so "dissociating the onscreen violence from anything in real life was easy", and that not everyone will have that upbringing. His 13-year-old nephew, for instance, is so obsessed with Call of Duty that he got kicked out of school because he turned up with a semi-automatic BB gun in his backpack. Parenting is a clear issue there, obviously, but there's a bigger issue too, and I think Smith sums it up well.

"If we want the vicarious thrills of violent video games to remain morally justifiable, we need to protect the fourth wall between the first-person shooter and real life," he writes. "EA's willingness to make a connection between a video game gun and an actual firearm is the strongest evidence yet that we've already let the wall crumble too much."

Maybe we shouldn't be surprised to encounter this sort of thing in a game that "goes beyond Afghanistan and takes the fight to the enemy in missions that have a dotted line to real world events" - a concept that no amount of collaboration with "the Special Operations Community" can render any less disgusting to my taste. And perhaps the fact that I only found out about it in the first place by reading an editorial on an American gaming website condemning it is encouraging, and this isn't just a cultural difference between the UK and the US after all.

I'd like to think so, because otherwise the idea of a video game spawning real-life 'merchandise' engineered to cleave people's skulls with tremendous efficiency, or to help you shoot bullets at people without having to reload so frequently, is completely normal to a bunch of people a few thousand miles across the water who, thanks to the wonders of technology, feel like they live next door.