LittleBigPlanet Vita review

Handmade, handheld.

It shouldn't make sense. What place does a game in which a chew toy jumps through shoebox dioramas filled with peeling wallpaper, worn rugs and offcuts from grandma's fabric drawer have on some of humankind's most technologically-advanced entertainment hardware? Sony's task is usually to cover up the joins in its work - to arrange the plastic, glass and buttons to resemble sleek, black pebbles popped straight from the future. It seems curious that a game hand-stitched in Guildford should have ended up the poster boy for Sony's corporate wonder-conjuring.

While no game would be better suited to sale on Etsy or a stall at an artisan fête, LittleBigPlanet's handicraft approach runs deeper than mere aesthetic - and it's here that the secret to the synergy is found. In play, you often notice the ropes and pulleys reeling past gaps in the scenery as doors open and bridges lower. The curtain flaps open so you see the sticks on which enemies animate into a scene; the craft behind the magic. You spy the machinations of level design, the digital nuts and bolts that work the level designer's ideas.

LittleBigPlanet shows its workings - not least via the powerful level editor with which much of the game's campaign was constructed - because, at heart, it is a game about the spectacle of ingenuity. I can't believe they did that, it hopes you'll say.

So too with with Sony's Vita, a futuristic miniature supercomputer that, with its surplus of features - two cameras! two touch surfaces! two analogue sticks! - also longs to impress via the spectacle of ingenuity. I can't believe they did that, it hopes you'll say. In particular, the bond between hardware and software is notable in this, the third game in the series, because the Vita's fat grab of features allows both game and console to amplify one another.

LittleBigPlanet's new developers - Tarsier Studios, Double Eleven and others - patch new ideas onto Media Molecule's original template, building worlds around the Vita's eccentricities. Rarely have game and system complemented one another so well while looking so incongruous.

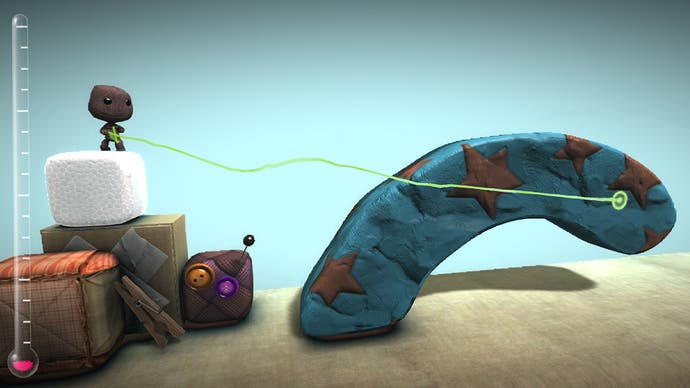

Which isn't to say that all of the tools given to Sackboy in this handheld game are novel. LittleBigPlanetary voyagers will be familiar with the angry rockets and grappling hooks that, over the course of the game, are strapped to their shoulders. But these tools have renewed vibrancy and vigor on Vita. Rockets can now be guided with the drag of a fingertip, weaving around scenery to stab through pink gloop and open up new pathways, or to sneak around the back of a clockwork baddie in order to hit its weak spot. The grappling hook - held back till the second half of the game - is now paired with the Vita's gyroscopes, allowing you to slide hook points across the screen as you dangle above licking lava, turning rope swings into zip-wires.

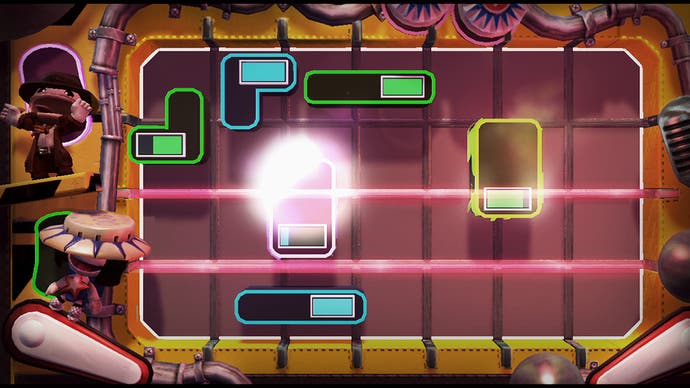

The touch panels offer the most obvious moments of invention. Blocks can be tapped into place - blue ones demanding a prod from the front screen, green from the rear - while there are many cogs that must be pulled into their proper place or springs that must be coiled and sprung to propel you forward. Not every tactile interaction is necessary to progress. At times these exchanges have a toy-like quality. Pianos can be tinkled (offering with a trophy for tapping out a specific tune), vinyl can be scratched - a surplus of playfulness.

Likewise, the offshoot levels - unlocked by finding keys tucked away in the main levels - have a joyful, throwaway quality, drawing heavily on arcade influences and making the most of the Vita's voluptuous screen and physical manoeuvrability. A Puzzle Bobble-influenced colour-matching game has you rotating the system on its side to create a giant portrait-oriented play board up which you sling the blobs with your finger. Another two-player example pits two robot boxers against one another. So effective are these mini-games that a number are clustered in their own Arcade world, with more steadily unlocked as you progress through the main campaign.

That campaign follows in the footsteps of the previous two games. There's a story of sorts, each world with its own antagonist and a welcoming character that requires your help. Despite the warm script, this often falls somewhat flat as, in narrative terms, Sackboy isn't much of a character. He's a cipher, a stuffed toy that can be dressed in another hero's costume, whose smile or frown is dictated not by reaction to plot or circumstance but by a context-free jab of the d-pad. It has to be this way in order to make sense of the level-building side to the LittleBigPlanet universe, but most players will impatiently hammer their way through the dialogue sections that punctuate the start and close of each level.

Still, the level design itself reveals Little Big Planet at its most rudely creative and exciting. New tools are introduced at a steady rate across the story, maintaining a sense of novelty and interest. Stages are long and winding and filled with creative flourish, while the expected rhythm of play is routinely upset with, say, a stage in which you must tilt the Vita to guide Sackboy - now in a Tron-like light-cycle, bounding off pinball flippers - to the finish line. It's bold and exciting, demonstrating an inventiveness that the overall game structure - identical to the previous games - cannot match.

Of course, LittleBigPlanet games are as much about the future as they are the present. By pressing one of the most flexible and powerful level editors into players' hands, Sony intends the community to sustain the life of the game long after the main campaign is put to rest. But with great power comes great fussiness, it turns out, and only the most determined would-be level designers will make it through the 67 tutorials with spirit-dampening titles such as 'Optimisation 2' and 'Advanced Logic 4'.

For those who merely want to splash about in the shallow end, the pop-it interface filled with stickers and objects is as intuitive as ever (you can now group items into your own categories for ease of navigation). You can now draw geometry direct onto levels, while the opportunity to point the Vita's camera and snap a texture or object in your house to include it in your level is especially convenient. For the more dedicated game-maker, the power to make wild imagination a wild reality is still there, although there is added slowdown when things get more involved as the Vita's brain aches to keep up with everything.

With space for up to 30 of your own levels, there's pregnant potential for LittleBigPlanet Vita to become a universe of interconnected ideas and places in the same way its forebears did. In defiance of the expectation that this out-sourced handheld update would be a second rate knock-off, the game builds on the past, rather than merely riffing on it. And in its own squall of ideas and creativity it invites you to contribute to the spectacle of ingenuity. I can't believe I did that, it hopes you'll say.