Okami HD review

Different strokes.

I've played Okami before. I've written a review of it before. (I can't say where, but you can probably figure it out and find the review online.) Daniel Craig's first James Bond film was in cinemas around then, and PlayStation 3 was on the point of release in Japan and the US.

That was six years ago - not that long in real terms, but an entire generation in the weird world of pop culture, where reinvention is everything. Now Craig is back on our screens, rebooting his reboot in Skyfall, and console gamers are once again wringing the last drops of enjoyment from tomorrow's useless plastic and looking forward to the next round. As Spinal Tap once sang: "The more it stays the same, the less it changes."

But as I explore Clover's wonderful, mystical adventure again in this handsome new reissue for PS3, I can't claim that I'm experiencing total déjà vu. This generation is not like the last, and you can scarcely find a better demonstration of that than Okami, a game that stands out even more now than it did in 2006.

It's not like director Hideki Kamiya and the Clover team were experimental renegades. Okami is a very traditional game. It owes a clear debt to Nintendo's Legend of Zelda series - another great respecter of tradition - as well as many other action and role-playing greats from Japan.

After a slow start, Okami settles into a very comforting rhythm - whether it's the percussive combo combat, the gentle pace of the upgrades, the tables of collectables to fill in or the soothing rota of exploration, puzzle-solving, dungeons and boss fights. All these familiar beats are woven together to give the game a hypnotic forward momentum as you, the mercurial wolf-goddess Amaterasu, reclaim feudal Nippon from evil, one floral explosion at a time.

It's everything you could want from a classical action-adventure - absolutely textbook stuff. So it's no surprise that the gameplay has aged very well. You could wish that the areas were a little more open, perhaps, and less broken up by loading screens, but that's all. Otherwise, it's still exemplary comfort gaming, backed up by solid controls, a snappy interface, well-judged difficulty and exquisite presentation. None of this needed changing - and none of it has been in a remaster that, visual fidelity aside, hasn't meddled with the source material in the slightest.

While all of this is what makes Okami good, none of it is what makes it special. It's where the game takes you that really matters.

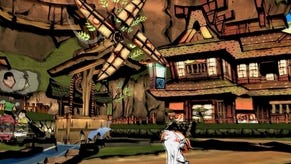

The stunning ink-and-watercolour visuals are just the start of it. Washes of pastel colour fill in the bold, thick, black lines of a calligrapher's brush, which are then animated with trembling urgency. It's very, very beautiful, and you cannot fault the sumptuous 1080p widescreen presentation of this new version. If it doesn't have the impact you expect it to, it's only because the original artwork was so timeless, and dodged technical limitations with such grace, that Okami can't really look any better than how you remember it.

"It's crammed with humour and pathos and colourful, bucolic characters who'll linger in the memory long after you've forgotten what it was you were fighting for."

Of course, the brushwork visual style is more than just beautiful. For one, it's a neat link to Amaterasu's Celestial Brush powers that allow you to pause time and paint symbols on the screen to do things like slice enemies, bring trees into bloom, or summon the wind or the sun. If you have PlayStation Move you can now use it to replicate the motion controls of the 2008 Wii edition, although I find that the original DualShock control scheme is surprisingly taut and easy to use. Either way, the Celestial Brush is a wonderfully tactile and appropriate allegory for the way the player can exercise godlike power over this storybook world.

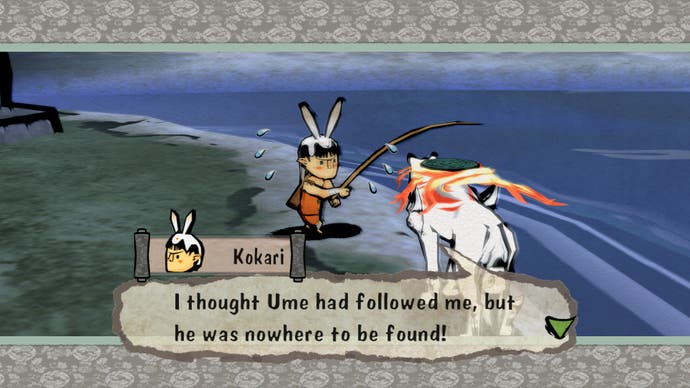

But it's that world which really stuns. It's very firmly rooted in Japanese history and myth, but spiced with irreverent invention and filled with all manner of spooky, weird and comical creations. The main storyline is almost irrelevant - this epic tale is strung together from a hundred human parables and vignettes. It's crammed with humour and pathos and colourful, bucolic characters who'll linger in the memory long after you've forgotten what it was you were fighting for.

Also - and this is one of Okami's greatest tricks - it feels truly ancient. Games aren't very good at the past tense, even when they're set in the past; it's such an urgent medium that what's happening on the screen always seems to be happening now. But via the visual metaphor of the art style, which appears to bring the illustrations on some old story scroll to life, Clover brilliantly evokes a world of 'once upon a time' and makes you feel like you're retelling a tale first told long ago.

"It's a classic game and an essential part of any collection, especially in this flawless, gorgeous reissue."

Okami's greatest stroke of genius, though, is the white wolf Amaterasu herself. When you're offered the chance to play god in a game, it's usually either as a jumped-up superhero or as a middle manager. In Okami, your god is an animal, with an animal's simplicity and wildness and connection to nature. You exist both above and below the human characters in the story; you walk among them unrecognised even as they praise you. Talk about a state of grace. This is a very different kind of deity for a game to present, one with a deeper connection to ancient myth than any God of War, and playing the part is utterly beguiling.

In hindsight, Okami does have flaws. Chief among them are its meandering pacing and ridiculously overblown length without true breadth; this is a long, long game that lacks the structural ingenuity of some of its peers. As good as it is, you will probably give up before you reach the end. If you're already familiar with it, that might discourage you from picking up this version and playing it again.

Buy it anyway. It's a classic game and an essential part of any collection, especially in this flawless, gorgeous reissue. And it casts you as a character like no other in a world like no other. In 2006, that was rare. In 2012, it's rarer still.

At the end of the last generation, Hideki Kamiya and others like him saw a mature platform as an opportunity to broaden their horizons and ours, to experiment with content and style within the established parameters. At the end of this generation, mainstream gaming feels more like it's just marking time before starting again. If only history really was repeating.