The Last of Us preview: Naughty Dog moves into Uncharted territory

Boston terror.

It's coming up to 8pm, and the crowd assembled in an LA warehouse for Sony's latest showcase event is slowly starting to thin. Evan Wells, a member of the Naughty Dog team since the days of Crash Bandicoot, is also making for the exit. He was up 'til 3am working through the demo of The Last of Us that we're being presented with today, and now he's heading back to stage and capture the screenshots that will accompany this morning's previews. Wells might be senior - in what's coming up to 15 years at the studio, he's worked his way up to studio director - but he's not above grunt work.

The reason it's Wells that's taking the shots, and taking on a job that'd normally be doled out to a less experienced member of the team is because, like all of his colleagues at the studio, he's a perfectionist. It's a perfectionism that's always been evident in Naughty Dog's games, especially so with the PlayStation 3's Uncharted series. Making adventures that are so breezy doesn't happen without hard work, and an awful lot of it.

But it's also a perfectionism that in the past has perhaps not left much room for the player. Uncharted 3, for all its indubitable splendor, was a game that was famously fussy whenever you dared delve from the script, and one whose strong sense of cinema sometimes detracted from the freedom that's expected of a video game.

The Last of Us is different. It's still undoubtedly the work of the studio behind Uncharted, even if it's being developed by a freshly-formed team within Naughty Dog's LA offices. There's the same interest in character and character development, embodied here by the central relationship between Joel and Ellie, and glimpsed in this first playable demo as Ellie's escorted by Joel and his partner Tess out of a dilapidated Boston that's been serving as one of the key quarantine points in a disease ravaged world.

"There is a sense that you're murdering people, and that's something that I wanted to explore with this game. Not so much to move away from Uncharted, but because it was an interesting challenge to say, 'I'm not the good guy.'"

Neil Druckmann, creative director

There's the gently overstated character animation, in which data from motion capture sessions is elaborated on by animators, giving every movement a distinct and characterized feel - and ensuring that Joel has the same slightly elastic feel in his traversal as Nate Drake, and the same grounded relationship with his environment.

It's also there, in part, in a sense of cinema that's shared between the two games, although it's here that The Last of Us and Uncharted start to take separate paths. Whereas Uncharted dips into the fantasy and adventure of Indiana Jones, The Last of Us leans on the grittier world of The Road and other post-apocalypse classics, telling the story of survivors struggling to stay alive 20 years after an infection has devastated the planet, leaving cities deserted and creaking under dust, the concrete cracking through blooming weeds.

Explore these cities, and it's a very different experience from the free-flowing adventures of Uncharted. The playable demo starts on the outskirts of the city; its ruined skyline visible on a grey horizon. Joel hulks himself up ledges, clearing passages in an abandoned office for Ellie and Tess by heaving around discarded photocopiers. There's a tension here though, that is unlike anything that Naughty Dog's conjured up in the past.

Once you're through the city, winding down through broken pavements and corridors until you find yourself in the dark cellars, it's a tension that's almost unbearable. Waiting in the shadows are the infected, people who've been struck down by an extreme illness inspired by the cordyceps fungi. They're a grisly bunch, their features shredded apart by an infection that attacks in stages.

First up there are the runners, those in the early stages of the disease who still retain some humanity, and who are powered by a sense of desperation. Their senses are dimmed, though if you find yourself in their sightline they'll make a line straight for you - ensuring that it's best to dart from cover to cover to avoid being overwhelmed.

Then there are clickers, those that are in a more developed stage of infection, their heads burst through with fungus, their facial features completely ravaged. As such, they're not able to see you, sensing you instead by echo-locating and demanding a slightly different form of stealth. Countering that, Joel's got the ability to focus on his surroundings - pressing down on the R2 button will wash the screen in monochrome, the outlines of the infected visible through walls.

The first encounters with the infected, taking place in the near-dark and soundtracked by a pounding bass thump, are deeply unsettling. Thanks to the savage consequences of an encounter, it's likely that they'll remain so throughout the game; if Joel succumbs to an attack from a clicker, there's a split-second view of his neck muscles being ripped off before the screen snaps to black.

The Last of Us, as has been made clear from last year's brutal E3 demonstration, is a violent game, and often to a deeply unpleasant degree. It's a world away from the sanitised slaughter of Uncharted, although it's necessarily so - whereas Nate's mass-murder was an extension of the matinee mayhem of Indiana Jones, Joel's killings tie into a bleaker vision.

"This game has a more realistic tone," says creative director Neil Druckmann. "There is a sense that you're murdering people, and that's something that I wanted to explore with this game. Not so much to move away from Uncharted, but because it was an interesting challenge to say, 'I'm not the good guy. And I'm not fighting the bad guy - I'm fighting other survivors and they just have a different goal to me.'"

Even when a barely human infected is the subject of Joel's violence, it's still unnerving - takedown kills using shivs that are crafted from everyday items are panicked, hurried and met with a fumbling splat. It might seem odd to praise a game based on a fanciful apocalypse for its realism, but there's an authenticity to every part of The Last of Us's world that helps make it all the more chilling, and all the more effective.

The authenticity is not just in the relationship between Ellie and Joel, or the real-world inspiration for the disease that's triggered humanity's downfall. It's also within the game's systems, and within the crafting that's central to The Last of Us's taut, frenzied combat. Here, items are constructed on the fly from everyday flotsam - scissors, rags and broken glass - to create weapons that are ferociously effective.

There's one other element in The Last of Us's play space, although right now it's the least convincing. Partner AI's an integral part of the game's make-up, where the relationship that's core to Joel and Ellie's story informs the moment to moment play - but currently, it's nearly non-existent, the non-playable characters happy to dumbly run around and reluctant to offer any help.

It's perhaps because, Naughty Dog suggests, that this early on in the game, Ellie's abilities still haven't fully evolved - and they're still working through how exactly she helps Joel throughout the game. "We played very early on with being able to give Ellie commands," says Druckmann. "Then she would do those things, but then we found out that you had an automaton by your side. It doesn't feel like a person. So, what if she could do those things, but on her own do those things?

"Having proven so adept at telling its own stories, The Last of Us feels like a Naughty Dog game that finally allows players to tell their own, offering a space in which there's a palpable sense of terror, and a broad set of possibilities."

"I was playing the game last night, and I had this moment not with Ellie but with Tess, but I didn't realize it was the last bullet in my shotgun. My back's up against the wall, and I realize I'm dead - and then all of a sudden this gunshot comes out of nowhere, and I look up and it's Tess. And I felt that was awesome - I felt like I had a partner in there."

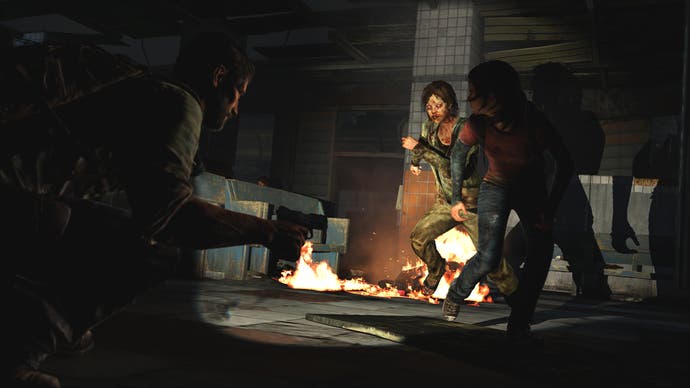

Having proven so adept at telling its own stories, The Last of Us feels like a Naughty Dog game that finally allows players to tell their own, offering a space in which there's a palpable sense of terror and a broad set of possibilities. Late in the play-through, we get to craft one of our own. With one bullet left in the stock of Joel's shotgun and a single freshly crafted molotov in his backpack, we're presented with a room with three creepers and a single runner; a grisly puzzle that plays out with grim results. The shotgun shell's used to kill the runner at the far end of the room, the Molotov used to disperse the two creepers standing side-by-side while the final creeper's seen off with a flurry of desperate hand-to-hand blows.

It feels like a big departure for Naughty Dog, far removed from the linear shootouts of Uncharted. "We're very ambitious sometimes, to the point where we drive ourselves mad," says Druckmann. "And we thought at an early point that we're going to go very systemic here, and probably beyond our experience. We do that with every game, we want to leave our comfort zone. But again, it felt like this game required it - if I'm going up against infected and humans, they have to all have this very robust behavior."

And it feels, after the tightly controlled action of Drake's Deception, that Naughty Dog's finally learning to let go, and to allow its players a little more freedom. Allowing that, and allowing the same level of polish and spectacle that has made the studio one of the most revered and respected this generation, could well ensure that The Last of Us is its most ambitious game yet.

This article is based on a press trip to Los Angeles. Sony Computer Entertainment paid for travel and accommodation.