The cult of Swery

Deadly Premonition's creator has become the focus of a phenomenal cult. How did Swery get here, and where is he heading next?

Hidetaka "Swery" Suehiro is a stranger in a strange land. Back home, he's the designer and co-writer of a string of quietly successful if anonymous PSP titles at Access Games, a mid-tier developer based in Osaka. Here, though, he's something else - a cult hero, and one of the few singular voices working in the industry. In a tour that's taken him from the sprawl of Los Angeles to Hitchin, the small English market town where we meet on a Saturday afternoon muted by snowfall, he's adored and revered. And it's all thanks to one very odd game.

Deadly Premonition, the open-world horror that's the embodiment of a cult hit and a game that hardly registered in Japan, has defined Swery. A struggle to make that saw little commercial success and a critical reaction so diverse it's gone on to earn a Guinness World Record for its Metacritic span, it's a game that continues to do so. Three years on from its release and Swery's preparing a director's cut, talking again to the fans that helped keep this strange, broken and brilliant game alive.

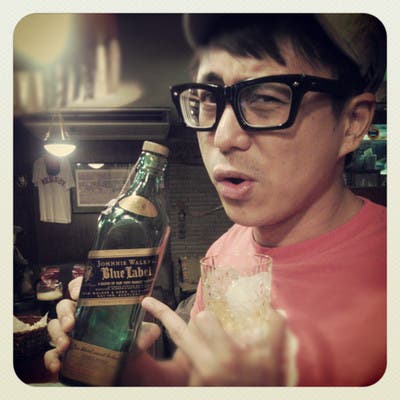

Swery's story begins in Osaka, a place that's defined the man and his output as much as any of his games. The third biggest city in Japan, it's renowned for jettisoning the reserved nature that hushes the rest of the country. It's a bright, bawdy place where excess replaces the minimalism typically associated with Japan.

As Swery's home, it's a place with a fitting eccentricity. "I can see so many strange people there, working there, drinking there," he says, his trademark oversized glasses bobbing up and down on his face as it wrinkles into his trademark oversized grin. "There are so many strange people in Osaka. And yeah, it may have affected me. To meet people in Osaka, it's very unique. If you aim your finger at anyone here, like a gun, the Osaka people, they'll react." Swery clutches his chest and staggers back as if he's just taken a bullet to the heart. "Everyone!"

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Swery's studies at Osaka's arts university were pointing him towards a career in cinema. "I was learning how to shoot a film," he says. "I was writing. Learning how to make, and how to express myself. I eventually came to understand that film was just one form of expression, and one form of creativity."

It's a form of expression that Swery could well have pursued. He was invited by the prolific director Sadao Nakajima, a product of the Toei studio system who has produced a string of genre films over the last 40 years, to draft a screenplay, an offer Suehiro seriously considered.

But something else was happening in Japan. Video games were making the transition from 2D to 3D, and a new world of possibilities was opening up for those who wanted to tell stories in a digital age. "The PlayStation and Saturn arrived - and the polygon started to appear, as a form of expression. So I started thinking that I'd be able to use my skill in filming in the video game industry."

Osaka in the '90s offered a wealth of openings for a budding games developer: Konami and Square had presences there, but it was the likes of Capcom and SNK that defined the region's output. Hard-edged, eccentric and with a strong western flavour, both outfits were producing the kinds of games that shaped the '90s.

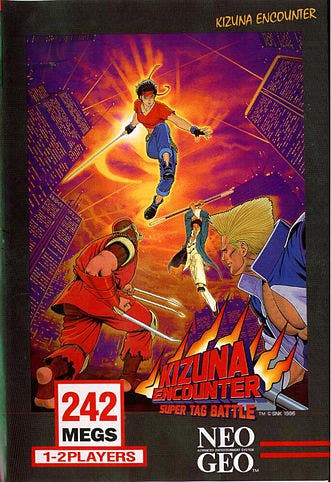

It was SNK that provided Swery with his first job in the industry ("the reason I chose them is that they were very close to where I lived," he chuckles). He joined them before their powers began to wane and while the original Neo Geo was still in full force. His first job was on 1996 fighter Kizuna Encounter, where he created the character of Kim Sue Il, a Korean police detective who deals out justice with a staff.

"I wanted to bring the Japanese games worldwide. In Japan, Osaka used to be the video games capital, with Capcom and SNK. Eventually, and now, Tokyo's where all the huge video game companies are."

Swery went on to create characters and scenarios for Last Blade 2, another brawler that alongside Garou: Mark of the Wolves is widely acknowledged to be among SNK's finest work in the genre. With Last Blade's reliance on the wuxia action cinema of Hong Kong, strong with mysticism and swordplay, it's tempting to see the filmic side of Suehiro beginning to take shape here. It was never to evolve any further at SNK, though, and after only three years he left to take a sabbatical.

"I went on a very long journey. I went snowboarding, I spent time watching movies, playing games - for 6 months or so." What was the thinking behind taking a break so early in his career? "I had no thoughts. I wanted to relax. But then I ran out of money, and I knew I had to find a job, and I had to make more games."

Following the calming comedown of 6 months vacation, his next job would plummet Swery straight into the fiery mess of console launch, working for Sony on the PlayStation 2 launch title Extermination. It was to prove a tough task. "The development of the console wasn't completed, but I still had to make a PS2 game. By the time I'd made everything, it was over the spec. After that, SCE fixed all the specs, and we had to complete everything in 8 months."

Given the circumstances, it's not surprising that Extermination, a survival horror that riffed heavily on the original PlayStation's Resident Evils, was no classic. It's a clumsy, cumbersome game, and one that doesn't dare stray too far from a formula laid out by its inspirations. "When I was making that game, I didn't have the chance to make the horror that I wanted," explains Suehiro. "I love horror, and I love the horror of Sam Raimi. But I'm thinking that I'm watching horror movies like they're comedies. The comedy part - some people don't quite understand what I'm seeing. They think it's a strange comment. I'm normally interested in a horror-based game, but nobody really understood my feelings."

Swery wasn't in charge of the script for Extermination, but he still managed to impart a personal stamp that would recur in his later games. Hidden away in the cast is one Forrest Kaysen, an overweight American based on one of Suehiro's friends. ("He knows that I'm using him. He asks, why am I included in my games? He does complain a bit.") "He's a very important character to me," Suehiro explains as he dismisses the theory that his games are all part of a shared universe. "He's just kind of proof that I created the game."

What happened after Extermination would allow for Swery's own tastes and idiosyncrasies to come to the fore. A group of producers, Swery included, splintered away to create a new developer with a clear identity and philosophy. "I wanted to bring the Japanese games worldwide. In Japan, Osaka used to be the video games capital, with Capcom and SNK. Eventually, and now, Tokyo's where all the huge video game companies are, with Nintendo, Konami and Sega all there in some way.

"Osaka's kind of shrinking for the video games industry - and I think we could bring it back. I think we could make Osaka win - that was my ambition in setting up Access Games. And it should have more uniqueness."

Access's first game, Spy Fiction, would be Swery's first in the role of director, and it's full of the surreal turns of dialogue that would go on to mark out Deadly Premonition. It's also schlocky and derivative - coming at a time when the stealth genre was in vogue, some of Spy Fiction's borrowings are a little too voracious - but Swery insists its inception was pure at heart. "I just wanted to make a spy game, really," he says. "I like spies. Chasing the possibility of what I could do with a spy game, by chance I reached the stealth action."

Spy Fiction, the product of a six-man team that was tinkering for the first time with concepts such as motion capture and English voiceovers, atones for its shabbiness with a set of ideas that forge an offbeat personality. There's more action here than is often the case in the genre, and its stealth is centred around the age-old pastime of dress-up, with new outfits unlocked by scanning enemies allowing access to new areas in the game.

"Spy Fiction's a kind of action game, and so the gameplay had to be really fantastic. The story must be fantastical also. Both story and gameplay must be a good combination. And I was chasing that down, following that idea at the time. Story plus gameplay - this doesn't happen in film. That's why I wanted to work in the video game industry."

"Story plus gameplay - this doesn't happen in film. That's why I wanted to work in the video game industry."

It's tempting to draw comparisons between Swery and his compatriot and fellow auteur Hideo Kojima, especially in light of the shared genre. It's not an affinity that Swery feels himself, though, dismissing any common ground between the two. "I met him just once, in a hotel bar at E3. We didn't talk much. He just said to me 'good luck'."

Spy Fiction wasn't to be a success for Access Games, its eventual release in America crippled by the politics that had ensnared its publishers. "The timing wasn't great - Sega and Sammy were together at the time. It was published by Sammy, but then Sega joined in, and so many producers from Sega were flown into the Sammy part. And they decided not to take this title - so Sammy's title had gone."

After the failure of Spy Fiction, Access was pitched into a series of work-for-hire games, including ports of Ace Combat and Sengoku Basara for the PSP as well as a Wii tie-in for Mamoru Oshii's film adaptation of The Sky Crawlers. Its defining work, however, was set to be glimpsed at 2007's Tokyo Game Show.

When Access's Rainy Woods first broke cover, it was met with a wave of incredulity. There are those that riff on existing material and have made something of a career out of it - see the assorted pop culture references of Kojima, or elsewhere Quentin Tarantino's lifting of Lady Snowblood - but the pine-tree Americana, mysterious dwarves and fresh blonde corpse suggested that Swery had been watching a certain cult '90s TV show closely.

Getting Swery to acknowledge his debt to Twin Peaks on the record is oddly impossible, as he chooses to either ignore or deliberately mishear questions drawing comparisons between the two. Ask who has imparted the biggest influence on his work and, bizarrely, it's Terry Gilliam and Brazil that he mentions first - although, as a cinephile, Swery has countless other inspirations. ("It is a very great film, but it doesn't mean I'd like to become like him. Plus I have so many people I respect. It's the Coen Bros. It's David Lynch, Woody Allen. Tarantino. And I respect Sam Raimi. And they all might have affected my career, and my creativity.")

Ask how the Black Lodge influenced the otherworldly elements of Swery's own vision and the answer's more earnest, even if it's ultimately as evasive. "In David Lynch, there's the red room and the white room - I wanted to express the human subconscious with those rooms. In these, the white's the normal condition - and if there's an influence of evil, that white room becomes red. That image, I don't know where it's come from. So I defined that white's good, and red's evil. That was the original concept."

Ask why the character of Emily in the game so strongly resembles the actress Naomi Watts - an iconic Lynch lead in the TV pilot turned full length feature Mulholland Drive - and the answer is more honest, although unfortunately it's one that he politely asks not to be put on record.

Perhaps it's due to a certain humility, or perhaps it's because such similarities contributed to the game's rocky development. Rainy Woods was cancelled before being reborn as Deadly Premonition, although its problems didn't stop there - production was threatened with cancellation a further four times over the next few years. (Again, there's a reluctance to say whether the similarities were part of the problem: "Well, it's very difficult to say," says producer Tomio Kanazawa as he squirms a little in his seat. "Let's just say politics!")

"I don't think of myself as a storyteller, but a game designer. Because I didn't design the story first with Deadly Premonition. First, I designed the town."

It's to Deadly Premonition's immense credit that despite its clear debt to the world that Mark Frost and David Lynch created with Twin Peaks it emerges with its own strong sense of identity. There's an affinity with Americana that's more than a faded photocopy, owing much to Swery's experiences of the States.

"Looking back at my history, I've been visiting Canada and Los Angeles, because I've got cousins living there. I've so many experiences of going there. When I was researching Deadly Premonition, I went to Washington - and I felt kind of nostalgic when I was there. And those experiences when I was younger must have affected me, creatively."

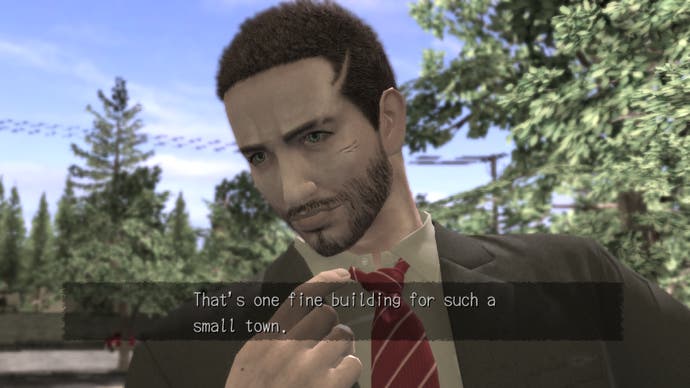

In the city of Greenvale, it's an affinity that bleeds into one of the most affecting open worlds created, a town where technical shortcomings are overcome by the clockwork life that strolls its streets, all brought to life with a disarming warmth and lightness of touch. It's those people and their stories that have earned Deadly Premonition so much praise, but it's the town that's fuelling them all. Ask Suehiro if he considers himself a storyteller or a creator of game mechanics, and his answer is enlightening.

"I don't think of myself as a storyteller, but a game designer. Because I didn't design the story first with Deadly Premonition. First, I designed the town. So I'm a game designer much more than a storyteller. Firstly, I created the scene - open world plus mystery. It was not a simple mystery game I sought. The most important thing that I sought was an open world. The town, as a setting, must be very interesting and fantastic, rather than the story. That's how I went about designing the whole country and town."

There's another star in Deadly Premonition, of course. When Rainy Woods debuted, it was fronted by the young, handsome David Lloyd Henning - and when it returned as Deadly Premonition a few years later, the role was taken by the slightly more oddball Francis York Morgan - played comically straight by Jeff Kramer, whose deadpanning as the voice of Seaman in Yoot Saito's Dreamcast classic had already earnt him a place as a cult deity.

"When creating Rainy Woods, the main character was young and very cynical," explains Swery. "And much more handsome. When it was cancelled, I didn't want to continue the same character. I had to start it from scratch, and I wanted to research it much more than before. So I contacted US friends to help create this new character of York."

York is Deadly Premonition's central character, the cipher through which the quirkiness of Greenvale is filtered, but unlike Twin Peaks' Dale Cooper he isn't a spin on the stranger in a strange land. The conversations between York and Zach, the mysterious other, make Deadly Premonition more of a buddy movie - and spring from a relationship that's key to Swery's working life. Kenji Goda, director of a handful of wilfully obscure films, has been a working partner for Swery since the two met while doing the motion capture for Spy Fiction. It's a relationship that's endured, the film-obsessed conversations the two share providing the inspiration for the conversations between York and Zach that delve into the nether regions of cult cinema.

"We are talking about a sequel. As for the setting - we'd be interested in Europe, definitely."

Since its release, Deadly Premonition's garnered a following as fervent as any of the films that Zach is enamoured with, and despite its mixed reception it's been enough to propel Access Games to create a director's cut version - marking a return to home consoles for the developer, which spent the past few years working on PSP game Lords of Arcana and its sequel. It's an opportunity to hone some of the mechanics - the shooting in particular was never a part of Deadly Premonition's original make-up and was added at the insistence of a US marketing team, which perhaps explains its haphazard implementation. The Director's Cut moves to address this, as well as some of the countless idiosyncrasies and rough patches of the original.

Moving to the PS3 will hopefully help Deadly Premonition find another audience, and there's a sense that it will have to find a sizeable one if the calls for a sequel are ever to be met. Swery's insistent that it's a world he'd love to return to. "Working on the other titles, we've been talking about Deadly Premonition. Always we've been thinking about it. Always.

"We are talking about a sequel. As for the setting - we'd be interested in Europe, definitely. We're talking about the next setting. It might work very well, we think. I said, as the producer, that York must appear. So I'm thinking that the main character will be York - and the other characters may be different. Do you know Columbo? He also solved mysteries in New York as well. So maybe we could be solving the mysteries in London - the main character can change place at any time."

Press a little further - and take into account the meagre financial success of the original - and a sequel seems unlikely. Can Swery ever escape the shadow of Deadly Premonition and make a game that resonates with the same power? He's got ideas that are brilliantly risqué - too risqué, sadly, to repeat - but it would take a brave publisher to back them and an even braver one to bring them to market.

The cult of Swery remains strong, though, even though it still centres around just the one brilliant, broken game. It's a cult that will hopefully spread with the release of the Director's Cut later this year, and as long as the enthusiastic, ever-smiling Swery is around, it's a cult that will never die.