Saturday Soapbox: Christopher Nolan has ruined video games

The Dark Knight director's cast a long shadow over this generation - but has it been for better or for worse?

Go to enough video game presentations and you'll soon start to hear the same hollow mantras dizzily ringing round again and again. Promises of more authenticity clang dully alongside promises of more immersion, more scale and more scope - and there's been a new addition to the thin lexicon of video game marketing in recent years. Games are getting more Nolan, and it's a trend I'm not entirely comfortable with.

I can't put my finger on exactly when the phenomenon started, but I've lost count of the number of times Christopher Nolan's been name-checked as a developer outlines their vision for a new game. At first, it was hard to bat an eyelid: games have always, for better and for worse, leant on Hollywood's most cherished, whether it's Call of Duty's keen attendance of the Bruckheimer and Bay school of shallow action or the pervasive influence of Scott and Cameron.

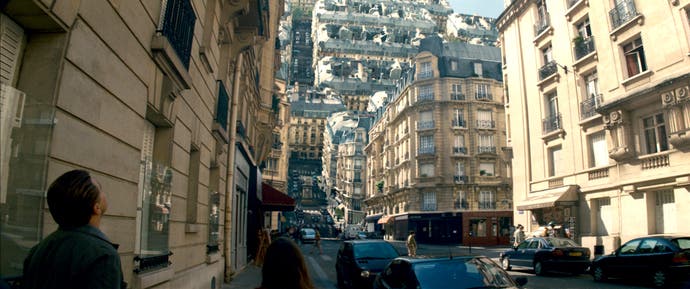

So there's nothing particularly wrong, or unprecedented, about Nolan being a certain strand of gaming's new cinematic love, and its new favoured crutch. If anything, he's the right man for games to turn to, his films literate in games to the point where it's hard not to see the influence of malleable digital worlds in cinematic labyrinths so dependent on systems and rules.

As someone much smarter than me pointed out in The New Yorker last year, it's so easy - and enriching - to read Nolan's films as games themselves. Memento with its swirling amnesiac trick played like a million JRPGs twisting back on themselves, The Prestige is like Spy vs. Spy with added theatrics and funnier hats, while The Dark Knight's so full of devious little puzzles and conundrums it feels like what could have been had Hershel Layton been born in Gotham and witnessed his parent's cold-blooded murder as a child. And Inception doesn't even require a leap of the imagination to see it as a cinematic game, its world a modder's paradise with a rule-set grounded in deliciously loose video game logic.

I'm not sure how much of that was going through the minds of the developers of Ridge Racer Unbounded when they blithely spoke of their love of Nolan's cinema at preview events a couple of years back, but I'm pretty sure it wasn't much at all. And as much as I loved ploughing through the concrete of Shatter Bay I couldn't help but feel that Bugbear was being hamstrung by a misappropriation somewhere along the line.

There have been more fitting carriers of Nolan's flame, but they're all just as wrong-headed in what they choose to plunder. I think, at some point a few years ago, a bunch of executives must have sat in some multiplex and paid dim attention to The Dark Knight, and then paid greater attention to the box office returns that followed - and we've been stuck with a wayward interpretation of a potentially great cinematic source ever since.

Video games seem to have Nolan's films pinned down as more gritty and more human, and while they're certainly the former, I'm not so sure about the latter part of the equation - it's a cold cinema that Nolan peddles, and there's never much room between the male posturing and twisting rules for much in the way of humanity. Regardless, there's much more to him than being the master of the gritty reboot.

You can see the appeal in that reading, though, especially in the case of long-standing franchises such as DmC and Tomb Raider that were in desperate need of a refresh. And it's easy to have sympathy for Crystal Dynamics, faced with the challenge of making one of gaming's elder icons relevant. It's a challenge, as studio head Darrel Gallagher's pointed out, that's been faced repeatedly by the likes of Batman and Bond, both of which are no stranger to the reboot process - some of which have worked, some of which haven't.

So it makes sense for Lara's new adventure to look towards the archetypal reboot success, Christopher Nolan's Batman Begins, but I think it's pilfered the wrong parts. Nolan's films, while inherently playful in structure and theme, are relentlessly serious, and it's a seriousness that's hardly their most endearing trait. It's also the one element perhaps most ill suited for many games.

Gritty's an adjective I'd rather keep well away from video game icons, characters we rely on for their playfulness and sense of fun. Who wants to play a Mario where we return to the plumber's roots, joining him as he's elbow deep in feces in some Brooklyn bedsit before he's forced to tearily stomp on his first goomba after it touches him somewhere it shouldn't? Actually, I think I kind of do, but that's beside the point.

And the Tomb Raider reboot's not a bad game at all, really, its tearing down and subsequent reconstruction of Lara being one of its finer elements. I don't think the writing, padded out with a flat and meaningless supporting cast and bizarrely pivoting on a damsel in distress, is any better than that of Underworld, though, and I certainly don't think it's any better for having taken the gritty route. Tomb Raider's endlessly and needlessly bleak, and after 12 hours I was just desperate for Lara to crack a smile. Come the climax you can't help but ask: why so serious?

It seems to have mistaken the croaky dryness of Nolan's films for something more profound, and ignored some of the more fruitful avenues his worlds suggest. It's like deciding that what you really want to take from a Michael Bay film is its human drama, sparkling dialogue and Shia La-bloody-Beouf. The triumph of Nolan's cinema is its intellectualisation of the fanboy film, and how its found broader audiences through plain smarts. It's a lesson that many video games would still do well to learn from - and if they're so keen to lean on his cinema, it'd be great if they could start paying a little more attention.