WipEout: The rise and fall of Sony Studio Liverpool

From the archive: The history. The legacy. The end.

Every Sunday, we bring you an article from our archive - and this week, to celebrate the original PlayStation's 20th birthday, we present the story of the studio behind one of the console's most iconic games.

In Hackers, the 1995 cult teen cyber thriller, a young Angelina Jolie and an American-accented Jonny Lee Miller play WipEout in a club. Established hacker Angelina is pretty good at the game, and has the top score. But then upstart hacker genius Jonny smashes it to bits. They hate each other. They love each other.

At the end of the movie Angelina and Jonny fall into a swimming pool and, finally, kiss, as Squeeze's little-known love song Heaven Knows lifts the camera up into the air. A year later, in 1996, the pair married. By then, WipEout, the racer that evolved from that pre-rendered demo Angelina and Jonny pretended to play on the big screen, was the most exciting video game in the world.

Improbably, a dozen or so people from a north west England developer called Psygnosis had conspired to stomp on Mario's head and speed past silly Sonic onto the cover of style magazines. WipEout steered into the slipstream of a dance music-fuelled drug culture, leaving its racer rivals in its wake. Forget beeps and boops - WipEout on PlayStation had heavy beats. WipEout was for grown ups. WipEout was cool.

On Wednesday, 22nd August 2012, 17 years after the release of the first WipEout game, Sony closed Studio Liverpool, née Psygnosis. The news sent shock waves rippling throughout the game industry, saddening hundreds of game developers and thousands of gamers. Sony had closed the door on one of the most influential - and long lasting - studios of all time.

For those who worked at Studio Liverpool and Psygnosis before it, it was the end of an era. Here, in a sweeping investigation into the studio's rise and fall, Eurogamer speaks to former staff about their time there, gains insight into the development of the many WipEout games and asks, why did Sony send WipEout to the scrapheap?

"You can't talk about WipEout without talking about Microcosm," Neil Thompson, who joined Psygnosis in 1990, eventually becoming lead artist, says. Microcosm, a 3D "shmup" set in some poor chap's intestines, marked the first time Psygnosis had combined its advanced 3D work, powered by its powerful Silicon Graphics machines, with live action and sprites. It was released on a number of platforms, but for Thompson the best version was for the long-forgotten Fujitsu FM Towns, the first hardware to come with a CD drive.

Psygnosis had experience with CG work and wanted to do an ambitious intro for Microcosm. It created live action assets - staff were filmed acting in front of a huge roll of blue paper bought from the local B&Q - that were mapped into the scene. The result is the video, below.

If you can forgive the hammy voice work you might notice a man in an orange jumpsuit. That's Nick Burcombe, who would later go on to co-create WipEout. The chap with the shades and the mobile phone is Paul Franklin, who won an Oscar for his effects work in the film Inception. Thompson's in there, too. "We thought it was pretty cutting edge," he laughs. Sony were convinced. In 1993, the year Microcosm released, it bought the studio.

Burcombe remembers the night WipEout was born as if it was yesterday. Burcombe had been playing Mario Kart at home when he turned the in-game music down in favour of some of his own dance music. Then, during a heavy drinking session in the Shrewsbury Arms in Oxton, Birkenhead, with colleague Jimmy Bowers, who brought with him ships he'd designed five years earlier for a game called Matrix Marauders, the concept of a future rally came together.

An early WipEout demo, set to brain-melting Prodigy track One Love, shows a different aesthetic to the one we know and love. The future rally WipEout was "very dirty, very grubby", Thompson remembers. "It was envisioned as a future rally, not the clean cut Formula 1 thing it became." But the wheels, or the anti-gravity device, was set in motion.

As WipEout was being worked on the people behind the movie Hackers came calling. They wanted Psygnosis to recreate WipEout for the film. Something super cool, something sci-fi, something fast. After a couple of weeks' work the result was recognisably the dirty aesthetic from the early WipEout demo fleshed out with a world and effects. As it turned out, Hackers and WipEout launched in the same month.

By September 1995 Psygnosis was owned by Sony Computer Entertainment, which had purchased the company off the back of the impressive work it had done with 3D graphics. Burcombe has his own unique way of putting it: "That's the company that was bought by Sony when they didn't know what to do about filling a CD up on PlayStation."

"From starting from a conversation in a pub, to a test video for a movie, to a piece of unknown hardware documented only in Japanese, to then, twelve months later having a working game on the shelf - it was an astonishing achievement," Burcombe says.

The WipEout team went to the PlayStation launch in HMV in Manchester and couldn't contain their excitement. "We were stood there proudly watching people pick up a PlayStation at whatever it was, four hundred quid? And there were three games. And as a matter of fact there were more WipEouts than Ridge Racers sold."

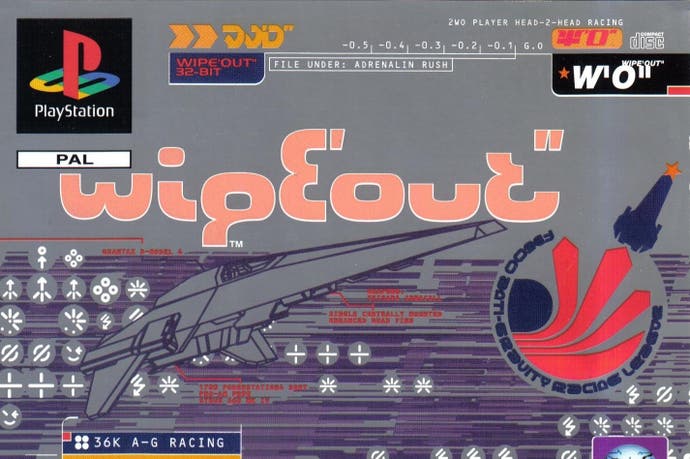

Those who were at the studio at the time say the release of WipEout was the culmination of a perfect storm of innovation, zeitgeist and marketing. Psygnosis had partnered with The Designers Republic, the Sheffield-based graphic design studio known for its anti-establishment aesthetics, to help create the clean cut look that would define the series. It created the iconic box art for the first, game, too, fondly remembered by Thompson.

"You look at the first one, still that is the most unique in terms of a fashionable statement. It was very much of its time. It wasn't a cynical marketing ploy. We were young and we were going to clubs like Cream. Dance music was huge and we liked The Designers Republic because they were doing the logos and graphics for the acts we liked and the CDs we bought. That's why it looks like that.

"This is beautiful artwork. I still think that's the quintessential cover."

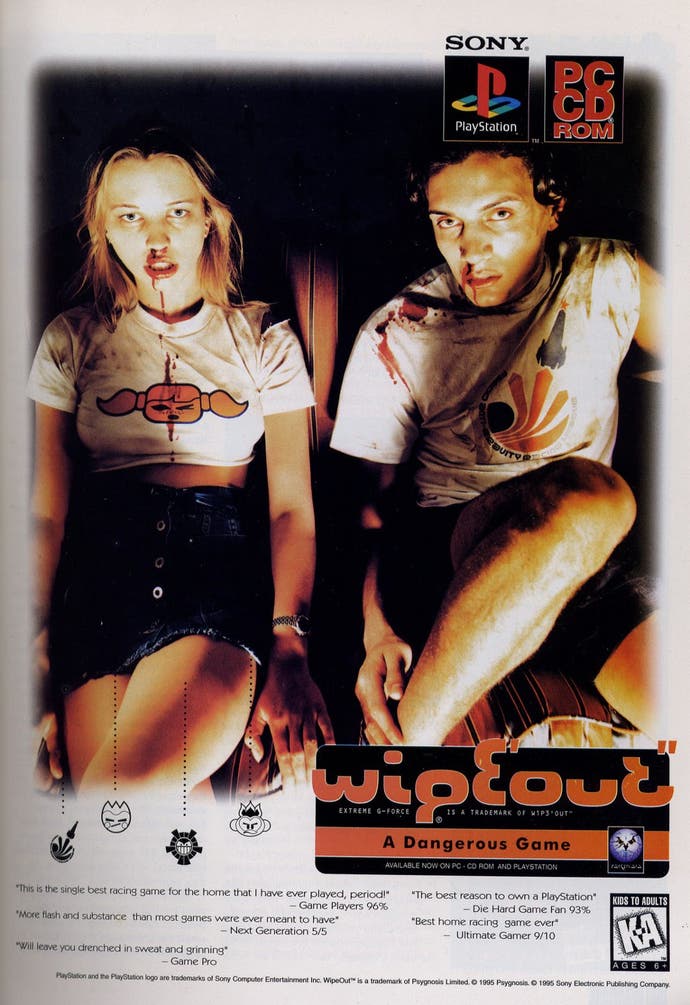

A delighted marketing department took the WipEout concept and ran with it. Its infamous poster, featuring a bloody Radio 1 DJ Sara Cox, was accused by some of depicting a drug-overdose. WipEout was "a dangerous game". And of course there's the capitalised E in WipEout. The legend goes it stood for the drug, ecstasy, top of politicians' hit list at the time. Was it deliberate?

"I've heard so many different explanations for this," Burcombe says. "It wasn't the big E as in E as in ecstasy. It was just the way that font had been designed. You wouldn't have been able to squish an E into that height of font. Every other letter in it would fit in a horizontal bar, which is effectively what it is.

"Maybe The Designers Republic wanted to put a big E in the middle to reference drugs culture. That was not my understanding of it at all."

"Absolutely intentional, obviously," Thompson says with a smile.

Whatever the truth, WipEout was reaching people other games couldn't. Its logo was in clubs, festivals and style magazines. "It was something fresh on the market," Burcombe says. "This tying together of club culture and gaming, people say it made gaming cool and acceptable in a different field."

It was also one of the first games to feature licensed music. WipEout's soundtrack is a who's who of British dance acts, including Orbital, Leftfield, New Order and Chemical Brothers. Looking back it all makes perfect sense - a no-brainer as the marketers might have said - but snagging the tracks was a hard job at first.

"I had my own shopping list because I was a bit of a raver in those days," Burcombe says, "and of course none of it was anything anyone had heard of. And if marketing were going to spend money on a piece of licensed music, which no-one had done before, they wanted to have a well-known name in there."

After a failed attempt to get Prodigy to sign on the bottom line, a 1994 meeting with brothers Phil and Paul Hartnoll, aka Orbital, was set up in their London studio. "I talked them through my vision of what I thought the game was," Burcombe says. "I was sat in front of two superstars in my view. It was a brilliant day, but I was nervous as hell. They were listening to what I was saying. They played a couple of tracks. It was like, um, that's not really working.

"They said, 'oh, we've got this track.' It was P.E.T.R.O.L. It was definitely in the right ballpark. It wasn't quite hard enough, but it still had that edge to it. It felt futuristic and cool." With Orbital in place, the rest followed.

WipEout's impact on the market meant the inevitable sequel, WipEout 2097, which released a year later in 1996. Burcombe is particularly proud of this game, which smoothed out its predecessor's rough edges. Blisteringly fast and blisteringly hard, WipEout 2097 built upon the good work of the first game and reinforced its place in the counter-culture of the time. Burcombe remembers taking gaming pods down to Cream and seeing WipEout 2097 within its hallowed walls. It was clear to everyone at Psygnosis and Sony that something special, something different, was happening. WipEout's beats were pulsing off of gaming's beaten track.

You hear within the studio the kind of rumours that are speculation on the internet now. 'Oh it's going to be able to do this. It's going to be able to do that!' It was exactly the same in the studio!

Jon Eggleton, former senior artist

Jon Eggleton joined Psygnosis as an artist in 1999. He remembers his first day at work, inside the huge L-shaped building in Wavertree Technology Park Psygnosis had moved to a few years earlier.

"It was very scary," he says. "There was a big reception area and lots of rooms where people were working on things and no-one was allowed in. That was building up to the days of the PlayStation 2. The first dev kits started to come in as I came in.

"Sony internal studios were just getting a glimpse of the dev kits at that point when I started. Suddenly there was all this scary, official business, and signing all these documents. It was a bit frightening."

Eggleton joined Psygnosis at a pivotal time for the developer. With Sony pulling the management strings, its long list of UK studios were streamlined. The Leeds studio, which had created WipEout 3, the final game in the series for PSone, was no more. A Manchester studio hadn't lasted long. It was time for a name change. Psygnosis became Studio Liverpool.

Around this time Sony decided it would put all its eggs in the Formula One basket. The license was considered a sure thing, and, after a round of shock redundancies in 1998, it was time to staff up once again in anticipation of the launch of the PS2.

"There was quite a lot of empty space, but within six months it was buzzing again," Eggleton says. "The fact there was a new console coming out always makes it really exciting. You hear within the studio the kind of rumours that are speculation on the internet now. 'Oh it's going to be able to do this. It's going to be able to do that!' It was exactly the same in the studio! Every leaf is going to be rendered separately on the PS2! I don't remember that ever happening. It all stays exactly the same.

"I remember all the early demos that came through with the interactive faces. We were like, 'This is going to be able to make a racing driver look like a human being now, and his car's going have every nut and bolt rendered.' When you look back it's daft. But it is exciting at the time because you imagine everything's going to be a quantum leap above what you've done before."

A lot of people who have been in the industry for a long time will talk about halcyon periods of development when everything just worked and it was great. This was the time at Studio Liverpool

Neil Thompson, former studio art director

Studio Liverpool's first game was Formula One 2001 for PS2. It had been intended to be F1 2000 and, believe it or not, a PC game, but it was pushed back a year after a big team of programmers helped switched development to PlayStation without much fuss.

The early years of the new millennium saw the release of a number of Formula One games and WipEout Fusion for PS2 in 2002. In April 2003, after a five-year period away from Psygnosis, Thompson returned to what was now called Studio Liverpool as a senior artist. He eventually worked his way up to art director on the F1 franchise.

"A lot of people who have been in the industry for a long time will talk about halcyon periods of development when everything just worked and it was great," he remembers. "This was the time at Studio Liverpool. There was a three or four year period when it was a really close-knit team and everyone loved what they were doing. We were passionate about the games we were making.

"I'm a big F1 fan so working on the game was just a hoot. I got the opportunity to meet all the drivers when I went to scan them for the meshes on their heads. I laser scanned Fernando Alonso. They had to do it with their eyes closed because they weren't happy about having lasers shone into their eyes before they got into an F1 car and drove it around a track. I don't know why."

It was around this period that talk of a WipEout reboot for the launch of the PlayStation Portable began. WipEout Fusion on PS2 hadn't set the world on fire, so Sony had given the series a rest.

Colin Berry, a veteran of the studio, designed what would become WipEout Pure for PSP. He'd worked on Fusion and had, according to Eggleton, become disillusioned with the way WipEout had been redesigned to ape games such as F-Zero GX. "He was always a big fan of the first one and 2097," Eggleton says. "There was a lot of enthusiasm to just basically wipe the slate clean and find out what it was people liked in the first place."

Studio Liverpool's approach to 2097 was to smooth out the famous WipEout difficulty curve and make the game more forgiving. Being a handheld game meant the team could create short races players could play on the go. And, of course, the game looked fantastic on the PSP screen.

We were used to DSs and Game Boys and things like that. When the PSP screen came in I remember thinking, that's not the final screen is it?

Jon Eggleton

Over the years Studio Liverpool carved out a reputation for creating eye-catching PlayStation launch titles. As a result, the developers would often get to tinker with PlayStation dev kits before other studios. It had done so with the PS2, and the PSP was no different.

"I remember the first time I saw that PSP screen," Eggleton says. "We were used to DSs and Game Boys and things like that. When the PSP screen came in I remember thinking, that's not the final screen is it? That's a big prototype thing. It's hard to believe it now because it looks tiny compared to the XL and the Vita, but at the time I thought, 'Oh, they haven't decided how big that screen is going to be,' but actually that was how big the screen was."

"We were pretty impressed with the way it shifted WipEout around," Eggleton continues. "It was a good showcase. It's a fast game so it was a cool way of showing how fast the hardware was, in a similar way to the way first PSOne title kicked a lot of polygons around and made it look a pretty impressive console. It sold a lot of PSPs in the early days, just from people looking over each other's shoulders and going, 'Oh, what's that?'"

As work on WipEout and F1 games continued, dev kits of what would become the PlayStation 3 arrived. The plan was to create a Formula One game for Sony's powerful and expensive new console that would show it off - Studio Liverpool's trademark. "We got an opportunity to get our hands on it early on, taking it apart and seeing what we could do," Thompson says. "And we could do a lot."

Studio Liverpool was proud of Formula One Championship Edition, and, in particular, its ground-breaking damage model. During development it created a test to see what would happen if it all the cars on the Monza track exploded at once. Would the game slow down? It didn't.

The PS3 launch was difficult, finances changed, the market shifted and the Xbox had arrived. The market dominance position of the PS2 was not going to be repeated

WipEout co-creator Nick Burcombe

"That was fantastic," Burcombe says. "A great project to work on. These were the heady days of PS2 dominance. In 2005 they took the entire company, all of SCE, to Malta, and put us up in hotels for a conference led weekend. It was so extravagant. It was the coolest company trip I'd ever been on.

"Every couple of years they used to do a trip for everybody to get together and do the Sony talks. But that was the last one they did. The PS3 launch was difficult, finances changed, the market shifted and the Xbox had arrived. The market dominance position of the PS2 was not going to be repeated."

Burcombe remembers his time creating F1 games fondly. He remembers team days out driving Formula 4 cars before an evening of go-karting. He remembers tickets to Silverstone. He remembers the Formula One Experience, driving an MG, then a Formula 4 car, then a Formula 3000 car, then, finally, a 1996 F1 car.

"It was really exciting times and it showed in the product. Championship Edition was a great game."

Formula One Championship Edition launched in Europe in March 2007. It was Studio Liverpool's final F1 game.

In September 2007 Sony bought MotorStorm developer Evolution Studios, based nearby in Runcorn, Cheshire, and Pursuit Force developer BigBig Studios, based in Leamington Spa, Warwickshire. By this time Sony's interest in the F1 license had expired. "It was an expensive project to do just on one console," Eggleton says. "It's the kind of project that needs to be multi-platform to make a big chunk of money. It's a very expensive license."

It was a muddled time for staff, who were thinking about what Studio Liverpool might do in a post-WipEout, post-F1 world. Prototypes were being worked on, as they always were. Enter lead programmer Andrew Jones.

"WipEout HD only happened because of Andrew Jones," says former WipEout lead designer Karl Jones. Andrew did some "black ops coding" off his own back to create a demo of what the PSP WipEout would look like running at 60 frames per second in 1080p. The demo wowed his colleagues and sparked development of what would become WipEout HD for PS3.

Now, five years later, Andrew Jones is modest about his role on the project. "There is some truth to what Karl said," he says. "I was looking at a few rendering demos and bits of code. I wanted to try out some shader effects and motion blur. And an extremely useful resource to do that was PSP assets for WipEout. So I, as a little side project, knocked together a rendering demo that incorporated camera shake and motion blur.

"Seeing that made a few people have a little bit of interest in the idea of using those assets and firing up a PS3 version. It's obviously a lot more complicated that that. The business side of things and what things were being planned... it's nowhere near as clear cut as Karl made out."

"Yes it is," Karl counters. "The fact remains that WipEout HD would not have happened had Andy not made that demo."

WipEout HD, the eighth game in the series, missed the PS3's launch, but it was the first PlayStation Network game to be considered "triple-A". It was a stunning technical achievement, yet another early showcase for what Sony's console could do. Even now, it is one of the few console games that runs natively in 1080p at 60 frames per second. Blink and you'll miss it.

We'd get drip-fed a tiny thing saying, 'if you had a touch-screen console, what would you do with it?'

former WipEout senior artist Jon Eggleton

As with the PSP and the PS3, Studio Liverpool was given dev kits of what was then called the Next Generation Portable. But unlike with the previous generation of hardware, Studio Liverpool was asked by the powers that be at Sony to influence the hardware's design, from its form factor to its unique features. This was in stark contrast to the approach taken with the PS3.

An NGP group was set up within Studio Liverpool to brainstorm the console and to promote it internally at other Sony studios. "We'd get drip-fed a tiny thing saying, 'if you had a touch-screen console, what would you do with it?'" Eggleton remembers. "Even though they hadn't officially said Sony will do a touch-screen console, we had brainstorming sessions of, just, hypothetically, if there was a touch-screen console what would you do with it? If it had an accelerometer, what would you do with that?"

Studio Liverpool came up with a number of ideas for the console. One was a biggie. "I've got a theory," Eggleton says, "that the reason the Vita has got two sticks is because Studio Liverpool said it needed two sticks.

"It's standard now. It's quite a disappointment when something like, say, the 3DS comes out and it hasn't got two sticks. So they repair it with an add-on. This was the first console where they came to developers and said, 'What would be ideal for you if you wanted to do games on this?' Between us and some of the other studios we said, 'Yeah, you need two sticks.' By hook or by crook you've got to shoehorn a couple of sticks onto the front of that thing, because one stick's not enough."

A year before the Vita would go on sale in February 2012, Studio Liverpool was given the go ahead to make a new WipEout game. The developers wanted to make it a Vita launch title, despite the blisteringly quick turnaround that would be required. "When they said, 'Right, we're going to have to get the game done by a certain time,' we thought, 'Well, you know what, we've got tonnes of ideas for WipEout we've never used. Why don't we use them in a Vita game?" Eggleton says.

The result was WipEout 2048, what would prove to be Studio Liverpool's final game.

Mike Humphrey worked at Evolution Studios on MotorStorm before moving to Studio Liverpool to work on WipEout 2048.

"The team was so well-oiled by that point," he says. "The core of the team had been there for such a long time that, I always said, if you left those guys in a room long enough they'd make a WipEout by accident. It was really smooth getting that game out. It was a lot of fun. We could get stuff up and running really quickly. Probably the most fun I had at that studio was getting WipEout 2048 made and then helping to promote that for the Vita launch."

"It turned out well," says Eggleton. "We were pleased with it. It's a shame we couldn't end up doing more with it, really. We had limited time and a lot of things in mind for following it up with downloads. But, obviously, it wasn't to be."

We had limited time and a lot of things in mind for following it up with downloads. But, obviously, it wasn't to be

Jon Eggleton on WipEout 2048

On the morning of Wednesday 22nd August 2012 an email was sent to Studio Liverpool staff asking them to gather for an announcement. Senior Vice President of Sony Computer Entertainment Worldwide Studios Michael Denny was waiting for them. He read out a statement - the same that would be sent to press later that day - that announced the developer would close down.

The statement:

The hundred or so staff were stunned. Those Eurogamer spoke to as part of this investigation told us they had no idea Studio Liverpool was in trouble. No-one predicted the hammer blow was about to land.

"It didn't feel like the place was winding down," Eggleton says. "We were full steam ahead with some new stuff. It was a big shock that morning, as it is with a lot of places I think."

Staff tell Eurogamer Sony treated those faced with unemployment well. During the consultation period staff were allowed to return to their desks to make sure they could arrange their portfolios to help them get new jobs. "There are much worse horror stories than what we had," Eggleton says. "You hear things about people getting texted. I'm glad it was done face to face."

"The first time I heard it, my only reaction was, 'Oh my god, are you kidding me?'" Burcombe, who set up Playrise Digital in Liverpool after Sony made him redundant from Studio Liverpool in 2010, says. "In my head - and I know this isn't even close to the truth - that was the end of Psygnosis.

"To me, there was an element of Psygnosis still running through that studio even though culturally it wasn't true. It was, for me, the end of an era.

"I was sad. I felt sorry for the guys because I'd been through that two years before and it's upsetting, especially when you've put so many years into a business like that. I know how passionate they were in that studio. They absolutely loved what they were doing. They loved making WipEout and they did it wearing their hearts on their sleeves. That whole studio can be very proud of it."

"I happened to be in the country at a friend's wedding when I heard the news," says Thompson, who now works at BioWare in Canada. "It was depressing. I saw a lot of press after that say, 'Psygnosis is gone and all those IPs are gone and WipEout's gone,' but of course they're not because the IPs are still owned by Sony. They could revive them again and get another team.

"I don't blame Sony. I don't feel anger towards Sony for closing that studio. There are always sound business reasons why a studio is shut down. But when it's a studio you've grown up with and poured your heart and soul into there's an emotional connection. I had an emotional connection to Psygnosis and Studio Liverpool. I was very happy there and we did some good games.

"Software companies like that are incredibly close-knit and you make very close friends because you're working very hard in close proximity. And it's terrible when it all breaks down and you have to go your separate ways. It's tragic."

Why was the studio closed? There are many theories (Sony turned down Eurogamer's request for an interview for this investigation). The most obvious is declining - or at least plateauing - sales of WipEout.

As it turns out, WipEout had never set tills alight. There is a misconception, fuelled by the impact the series had in its early days, that WipEout sold many millions of copies around the world. The simple truth is that it did not.

But, as it turns out, WipEout had never set tills alight. There is a misconception, fuelled by the impact the series had in its early days on the first PlayStation, that WipEout sold many millions of copies around the world. The simple truth is that it did not.

"There was a perception within Sony that with a WipEout game you were only ever going to sell a certain number of units and it was never going to break out and be the three, four, five million-seller you would want that would make it a really huge hit," Thompson says. "It wasn't as commercially successful as people believe. It's not like Call of Duty kind of numbers."

"I'm not sure WipEout was a massive hit," Burcombe agrees. "It had a massive impact, but it wasn't a massive hit in terms of sales volume. It got a leg up from being one of the few launch titles on PlayStation, but these days a good seller is huge numbers."

Modest sales, though, do not tell the full story. Studio Liverpool was a huge triple-A company with high overheads that specialised in a declining genre Sony had covered with Evolution. Its closure came as a surprise, but for many it made sense.

"There are a lot of different things that are affecting studios at the moment," Humphrey suggests. "Maybe people aren't buying games as much as they were before. Maybe towards the end of the life cycles on particular bits of hardware people don't want to go and buy the same kind of games again.

"But we don't really know the reasons why. It's really easy to wallow in the past and think too much about it. It could just come down to numbers in a spreadsheet; a certain number was a minus instead of a plus and that means a bunch of us don't have a job any more."

Thompson suggests WipEout failed to reinvent itself throughout the course of its life. "It's not a fashion statement of its time, whereas the original WipEout was," he says.

"What I would have liked to have seen - and I don't know whether the business would have supported it - was WipEout to evolve in its look and its music and its fashion, because it was still harking back to The Designers Republic thing. That's the past. That was my youth, not the youth of today. What are they into? You want to write that game with the twenty-somethings who are writing games now, and say, 'Right, you take it.' Call it WipEout. That's the dynamic. But what's the aesthetic? What's the soundtrack? What's the look? What's the design ethic?

"It's difficult when there's an idea that the success of a project is down to a specific look or a specific aesthetic and there's a pressure on you to recreate that time and time again, because if you don't, it's not WipEout.

"But I don't think that's what WipEout is. WipEout's not an aesthetic. It's a time capsule. And the time capsule should be updated. You should open up the box and pour more stuff when you do another iteration. That would give you another time capsule from 2012."

Eggleton believes Studio Liverpool managed "a certain amount of reinvention", mainly focused on combating its famed difficulty. "The reinvention we were trying to do as the series went on was make it so people could sit down and play it and not feel as if they were getting their arse handed to them every single time, that people who would play a regular racing game that was a little bit slower and a little bit more forgiving could pick up and play a WipEout game without being frightened to death by it.

"People did accuse it of not reinventing, but you only had to see a screenshot of a WipEout game and you knew exactly what kind of game you were getting. No-one ever reinvents football games. We just thought, it's not really broke so we're not going to make too much of an effort to fix it."

"The whole team was very aware of what the core of WipEout was," Humphrey says. "We really understood the DNA of it. There's only so far you can move away from it before it isn't a WipEout. Early on in 2048's life cycle we had this conversation, as I'm sure the guys did on every WipEout after the first one. What do we do different? You throw a lot of ideas around, and it always comes back to the same thing: is that really WipEout? Is that what our fans want?"

There's only so far you can move away from it before it isn't a WipEout

former WipEout lead designer Mike Humphrey

Was WipEout a victim of its own difficulty, then? Some believe the perception created by those early, brutally tough WipEout games stuck with the series throughout its life, forever putting prospective newcomers, or even lapsed fans, off.

In the beginning, WipEout's creators didn't set out to deliberately punish players. "We just set it up so it was fun for us to play," Burcombe says. "Those days are long gone now. As long as you were having fun with it, you thought it would be fun for everyone else. And actually, when people got over the massive hurdle you put in there, when they understood the controls and it took practice, once you got it, the satisfaction from the gameplay was absolutely immense.

"But it was a very high barrier to entry. You couldn't get away with it these days."

"We addressed that, particularly with WipEout 2048, but I think at that point people just saw WipEout as the hardcore game," Karl Jones says. "You look at WipEout on YouTube and it's intimidating. Maybe the intimidation factor was a big deal. We addressed it in 2048, but maybe we should have addressed it a little earlier than that.

"WipEout had this reputation for being too hard, too fast and too hardcore. I don't think it managed to shake that off. Ever. It's part of the DNA. People knew that, and once bitten, they weren't going to back to it.

"It's a victim of its own thing. You look at a screenshot of WipEout and it's unmistakably WipEout. Some people looked at some of the later versions of WipEout and just saw the early ones, and they thought, well, I couldn't play that.

"These are all things we were aware of and attempted to tackle. How successful that was I don't know."

Burcombe reveals one failed effort to reinvent WipEout. "One of the concepts we did - I actually thought it was very good - was much more freestyle. It was like WipEout meets Parkour. You could race on anything. You could jump on top of cars going past and all sorts of stuff. But that would have been a completely different type of product.

"WipEout became a formula no-one dared break. The WipEout audience, even if it was a fairly fixed size, would want it. They wanted to make sure it was the best WipEout each time.

"WipEout's an unusual one. You cannot make people like futuristic racers just because the quality has gone up or it's got more tracks. The audience is much broader now. It is actually quite niche, if anything.

"So for me the series always evolved and did new things and was innovative, and supported Sony's strategic agenda, and it did it very well. It was there for launch of PSP and Vita, and it was there for PS3 as a flagship for PSN. But with team sizes always growing and production costs going up, if there's a limited audience of a fixed size, you've either got to do it cheaper or change the game so it attracts more people. Is there a massive audience out there waiting for a futuristic racer as well as a Grand Theft Auto or a Call of Duty? I'm not sure there is.

"They had an audience. I suspect it wasn't growing. But if your team is growing and your costs are growing, then you're not going to be very profitable, are you? You could sell a million copies, but can you do ten million? No. There are not ten million people out there waiting for this game."

Andrew Jones is philosophical about the closure. "Being in the game industry sometimes felt like the scene in Pulp Fiction when Jules and Vincent narrowly avoid being gunned down by a guy who pops out of a kitchen. They look behind them at the wall full of bullet holes, and then look at themselves unscathed.

"Translated into the games industry, this meant that, even halfway through my career I'd been in close proximity to studio closures and colleagues being made redundant. It was very clear working in the games industry meant a certain level of insecurity about the company you were working for and the studio you were working for. I thought the best way to operate with that was to accept it and to plan around it."

Studio Liverpool is no more, but it will always be remembered. It created too many influential games, as Psygnosis and then as Studio Liverpool, to be forgotten.

But how will it be remembered? What will be its legacy? WipEout, former staff say.

"It will always be remembered for WipEout and what that meant to Sony as a whole," Humphrey says. "That game's got a special place in a lot of people's minds. It really defined PlayStation. It wasn't just a kid's toy. It was something for the cool older kids, maybe."

"I remember playing the first WipEout," says Eggleton. "A week before I'd been playing Yoshi's Island and boring everybody stupid. And then suddenly I was playing something that looked like you were in an arcade."

"WipEout was the game changer," says Burcombe, proudly. "It changed who we were targeting games at. Games had always been targeted prior to that at the 12-16 year-old market. At 16-years-old you're meeting girls and going out and having a good time, right? But this was different. This made the industry, not mainstream, but underground and cool.

"If you said to someone twenty years from now, name a game Sony Liverpool made, they would say WipEout every time."

"WipEout was launched and it just hit," says Thompson. "You look at it now and you look at that cover and the way it was marketed, and you think, that's a mature game. Not mature as in adult. But mature as in, it's not a kid's thing any more. It's something for young adults and it responds to what young adults are into and the fashions of the time.

"That's what WipeEout's legacy is really. It made games cool."

"All of a sudden this was a game you could put your name to and actually look cool," suggests Andy Jones. "The cutting edge visuals and the licensed soundtracks and the adrenaline and the speed in this perfect package, which has always been what WipEout's done well, that crystallisation, and then our association with that transition of gaming and representation of cool in a game form that had mainstream acceptance, is probably WipEout's biggest legacy.

"Although, definitely, all of the programming I did on WipEout Pure."

After closing Studio Liverpool Sony found a home for many of its staff elsewhere within its empire, but many were put out of work. Some have found new homes in new studios across the globe, but many remained in Liverpool. The city's "Baltic Triangle" is buzzing with start-ups such as Lucid (formed from the ashes of Bizarre Creations) and, now, Sawfly, which Karl, Mike, Andy and Jon set up a couple of weeks after being made redundant.

"You've not heard the last of Studio Liverpool, I'll tell you that," Eggleton says, defiantly. "The name won't come back, but every other person who comes out of the Liverpool development community now will have at least one Studio Liverpool project on their CV somewhere."

While Sony may one day reignite the WipEout franchise, it seems that with Evolution's Drive Club and Polyphony Digital's inevitable next-gen Gran Turismo already in the garage, the launch of the PS4 won't enjoy a WipEout game.

Eurogamer has heard whispers that Studio Liverpool was working on a WipEout game and a Splinter Cell-style game with advanced motion capture tech before it was closed down. Staff can't talk about these secret, cancelled projects on the record, but they can talk around them.

"I would have loved to have got to make another WipEout," Humphrey says. "I'm gutted I only got to make one. After the announcement of PS4 it sounds like it's an impressive bit of kit. I definitely think WipEout would show it off to its best. It would have been great. But there we are."

"Yeah, it would have been good," Eggleton says with a chuckle. "It would have been very good. My only worry would be topping WipEout HD because that turned out so bloody good. But yeah, it would have been fantastic to see another one. You never know... You never know."