Captain Forever: A space odyssey

How a free Flash game took Jarrad "Farbs" Woods into orbit.

In June of 2009, Farbs - who on Earth is often known as Jarrad Woods - quit his job at 2K Australia and set off for the stars. Within a few months he'd reached his destination, spinning through a Petri dish cosmos, blasting whirligig enemies when they swarmed in from all angles, and picking over their remains once the killing was done. His launch vehicle of choice was a freeware Flash game called Captain Forever that took him mere weeks to construct, and in the years that followed it has spawned two richly ingenious sequels. With work on a far more elaborate fourth instalment now under way, it seemed like a good time to find out how things are going - and to look back on the journey so far.

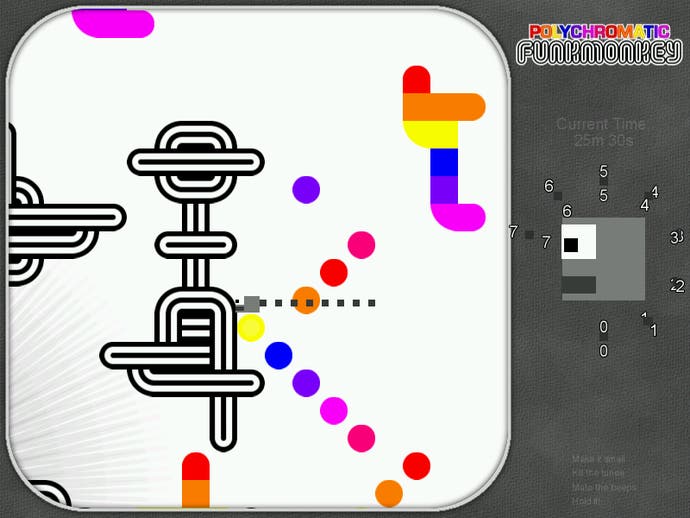

Prior to leaving regular employment, Woods' freeware output was characterised by an antic cheerfulness. Rom Check Fail pulped 8-Bit classics into an epileptic fugue where the objective never changed but just about everything else did, while Polychromatic Funk Monkey saw you racing through the background of what looked like some tuned-in 1970s kids' show, rearranging rainbows and leaping from one curved ledge to another as you activated a series of totems. It was a good life - I suspect you couldn't make games this relentlessly chirpy if it was anything else - but a trip to GDC ended with Woods calling his partner from San Francisco airport and telling her that he had to quit his job. Time to go solo. Time to start the countdown.

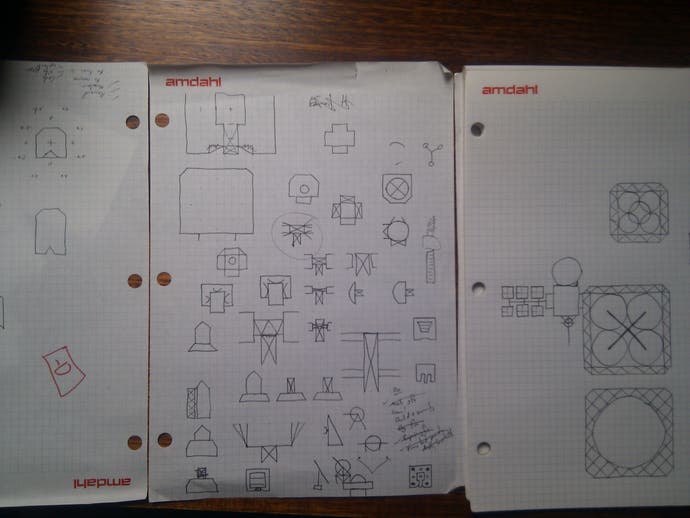

Did Woods have an image in his head of what a Farbs game should look like? "It's more like your games choose you," he laughs when I catch up with him on Skype. "So on my first full day, I sat down at the kitchen table with a pen and paper and listed all the game ideas I'd been thinking about for a while, and tried to pick which one to do. I really did not have an amazing plan. But I've got to say, just the other day I listed out all my games and other projects to have a think about them, and I was kind of surprised. I've always been a bit interested in construction and making things, but when I looked at all the things I've made, that's a really heavy theme running through there."

That's certainly the case with Captain Forever, a quick-witted splicing of building stuff and dismantling other stuff that encourages you to tool your way around the universe in a ship whose design is entirely mutable. It's a game of space junkers, but with cool neon edges in place of the rust and grit that usually accompanies chop-shop mentalities.

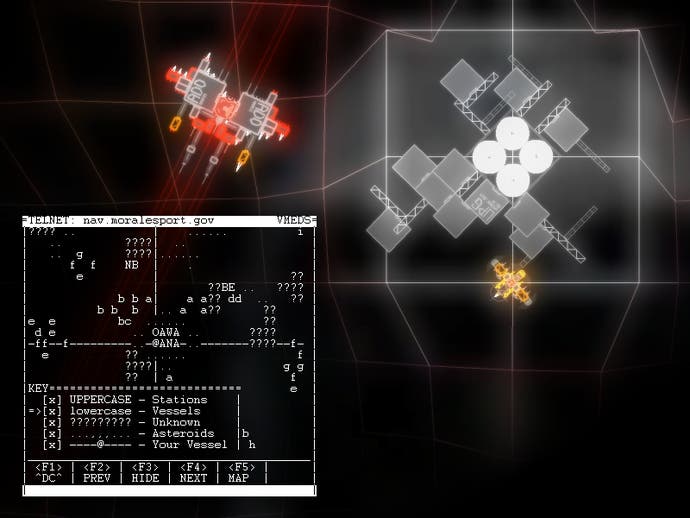

I first encountered Forever while sat at my own kitchen table a few years back. It initially cuts a rather daunting figure, with its angular sylphs slipping by against a backdrop of slender oscilloscope lines, while text scuttles past at the bottom of the screen and each burst of laser fire reveals a ghost - a misted image of yourself - watching the action as it unfolds. In truth, though, few adventures are as immediate in their pleasures. After bolting a few girders, thrusters and weapons to your bright red command module, you're off to duke it out with pirates. When you've defeated one, you get to graft any remains onto your own craft with a few quick sizzles of your magical deep-space welding torch. Your trophies become a part of you, so shoot carefully. Work quickly too, because fresh waves of enemies are no doubt approaching while you're remodelling.

Captain Forever has a clear lineage in two of Woods' favourite freeware games: Warning Forever, Hikware's luminous boss-rush shooter, and Battleships Forever, an RTS follow-on made by Wyrdysm. From the former, he took the idea of flimsy disco spaceships which needed their wings shot off before the core was attacked. From the latter, he was inspired by the elaborate editor.

All of this clicked with something else Woods was pondering at the time: the idea that meaningful game rewards should change the way you play. "Captain Forever was me trying to find the simplest, slimmest game I could make to embody that concept. That's why you're not running through a huge story, and why the other ships just come right at you rather than you zipping around to find them."

The shooting's great, then, but it's just part of a game that revels in freedom of expression. Occasionally I like to export my latest Forever craft to my Facebook page, and I'll sometimes receive a little feedback, too. "Move that module to the left and it won't list any more," says an annoyingly brilliant friend of mine whose own ships resemble dread fairy-tale castles, riddled with perfectly placed finials and crests. I can never bring myself to admit that I kind of dig the way a ship lists, just as I dig the way that my worst ever construction had the boosters so badly applied that it would only turn in lazy circles when I applied full thrust. The guns, meanwhile, were partially stuck on the inside, meaning that each volley of shots did as much damage to me as my foes. RIP, Clanky Van Dangerbot.

"Sharing crafts was something I started seeing early on in Forever," says Woods. "I leapt into an IRC channel to share the game and people would start sending me screenshots of what they built. You have the people who are playing to win the game and who just use five pieces they upgrade throughout, but what I really love seeing is people who build hoarder ships where they just have to keep every single piece. You end up with this enormous useless hulk with these low-level parts that you have to keep safe by surrounding them with the next parts up, and then the next parts up."

If Captain Forever brought Woods a community, his next game would have to deliver an income. "Forever was the game people could play for free, and then Captain Successor was building on that," he says. "I was getting bored with the modules in Forever - two kinds of weapon, two kinds of girder - so I thought: let's put lots of different things in there, lay on different personalities for the AI ships and have them constructed in different ways. It was the obvious way to go with it. That's why I called it Captain Successor, really."

To ensure Woods wasn't destroying the simple magic of Captain Forever by turning it into a cosmic yard sale, he was careful when adding new elements. "I just kept checking that everything added to the game didn't cover stuff that was already there. There's no laser that's just twice as powerful as another laser and otherwise identical. There's the sniping laser that has half your firing rate but twice your range. That was enough to create a wide variety of games as you're playing through it, and that was my goal."

Successor was Forever Plus, but Woods had strange ideas on where to take things next. How about meddling with the core of the game? How about creating a version where you couldn't bolt new pieces on anymore, but you could attach yourself to an enemy ship and clone its design wholesale?

"For me, Captain Impostor's about deliberately unlearning the lessons of Forever and Successor," says Woods. "I found I was playing those games the same way a lot of the time. In Impostor, you don't have that choice. You have to take pretty much what comes along. And then half of your ship gets blown off you have to find a way to make it work. I really love that about it, but I know it frustrates a lot of people."

Frustration isn't quite it, I suspect. Forever and Successor feel a little like the enthusiasm of youth: you can ramble around from one idea to the next without ever worrying too much, and every fight leaves you with a sense that you learnt something cool from it or did something worthwhile. Impostor screeches in like middle-age. Suddenly things can go really badly wrong and you can make mistakes you realise you'll have to live with for a while. "It was never intended to be the future direction of the Forever games," allows Woods. "It was more a zany off-shoot: hey what happens if we do this? But I really wanted to experiment with having to fly ships that I hadn't built myself. I wanted to learn to fly terrible half-built hulks and see if I could make that work."

After a straight sequel and a burst of experimental madness, Woods was ready for something bigger. Enter Captain Jameson. The definitive Forever game, a grand RPG, and an adventure whose mere choice of title hearkens back to the days of starfield-spanning sagas where a whole galaxy was there for the taking. Is this Woods' attempt at Elite? It probably would be - if he could finish making it.

"Basically, when I first started thinking about Forever, I really wanted to build a huge world around that and have you explore different places and interact with different things," Woods admits. "I quickly realised I had no chance of doing that at the time. This is one of the reasons I built this thing as a series - so I could incrementally build up. Successor added new modules, and then Jameson takes all of that content and wraps it into a big meta-game of exploration and finding your way through the universe."

I've been following the stop-start development of Jameson for a while now, getting excited as each new blog post announces the addition of mining, or a new docking system for space stations, or, y'know, space stations. Every time a new build is available, I rush in, hoping to get a true sense of what's being laid out here. Woods talks a lot about game design as a process of navigating the possibility space of an idea, and it seems that the possibility space he's marked out for himself is, well, dauntingly large. It makes me wonder if Jameson was ever designed to be finished.

"There have been several concepts of what it should look like when it's finished," laughs Woods, "and that's part of the problem really. I started building Jameson at the same time that everybody was starting to look at roguelikes and say, hey, what if we applied some of these ideas to different genres? Some really amazing games have come out of that: Spelunky, Binding of Isaac, FTL. People have really been pushing into that stuff and exploring and making wonderful things. Now they've made those games I can see how they've evolved the genre and what's working there. To some degree, I think I'm playing catch-up." He pauses for a second. "Basically, I had an idea about how Jameson would work, I built it, and it was just wrong. It was not a good game."

Ouch. "I got it to that point where you could play the game from start to finish, and a few of my core concepts about how the game should work were just wrong," he continues. "Primarily, you'd fly one ship out to a station, then you'd transfer your pilot who would become the new station administrator. The station would become active, and then the next thing that would happen would be that you could then use that station the next time you played."

Even I can see where this is going to go wrong. "Unfortunately," Woods continues, "you'd also lose your spaceship. The idea was that you'd play game upon game upon game and slowly populate the whole area. That seemed like a really good idea, but it basically meant that people were losing their ships before they were ready to. They didn't particularly want to do that. And they were getting a small reward for it."

Woods was in trouble. "My big concern was that if I took that stuff out, the game would go back to being the size of Forever, and you could play an entire game in ten minutes." He laughs. "That clearly didn't fit with the grand, sweeping, epic plans I had in mind. So I wracked my brains, and I was really freaking out over it for a couple of months. I was really worried about how I would solve this problem and save the project.

"It wasn't until Jon Chey, who I knew from 2K, contacted me and asked if I wanted to get involved in a new game called Card Hunter that it got resolved. I knew I needed to think about something else for a while and this little card game that's going to take me a couple of months seemed like a good idea. Maybe a week after that, I got back to thinking about Jameson again. I thought: the obvious solution is that you unlock the station and just keep playing. Why don't I just try it?

Woods did. "And it turns out that's fine. It's fine. Great. So months of agony about not wanting to change a core decision were just wasted, because I could have spent an hour prototyping the change and seeing it's pretty good."

So now Woods' job is populating the universe he's built. It's a big place. "This is just back of the napkin stuff, but I think the explorable area in Jameson at the moment is about one and a half times the size of Wales," he laughs. "I also have to make sure it's filled with interesting stuff. I'm getting there. There's ships to find, mining has its own exploration aspect because some asteroids have cool stuff and some don't, so you want to prospect by shooting asteroids and seeing what falls out, and there's all these different stations with different abilities and cool things they can do for you. Then you can hop between sectors, and you might go from some place that's pretty stable to somewhere that's filled with lava rocks and you have to ever so carefully inch between them, and defeat your enemies by pushing them into them. Then you'll find places that are huge but sparsely populated by these massive megacities. So there's stuff there but I still need more stuff. I have to make sure the skeleton is right before adding fancy clothes."

It sounds glorious, but rather terrifying. To Woods, though, it's fundamentally pretty simple. "For me, Jameson is about making and adjusting your plans as you play. You'll be sitting somewhere and say, well, there's a refinery here and a bunch of asteroids. Why don't I check out the asteroids and see if there are any decent minerals in there so I can sell them, then I'll go over somewhere else and buy that thing that I saw but can't afford yet but which will help power up my ship? So there's your plan.

"So you'll go over to the asteroids, but then you'll see a derelict ship that's hidden in there. You'll see it, and decide to take it. You blow it up and you've got all these parts. They're not going to help you mine anymore, but they're still good, so you take them to a scrapyard. Except the scrapyard's too low-level and then you have to hop sectors to sell the scrap at a yard that's the right level so that you can then come back and buy the ship parts that you wanted in the first place."

He claps his hands together triumphantly. "That's what Captain Jameson's all about."

I sense we're still a little way off, though, and Woods agrees. "I have a bit of love-hate going with Jameson at the moment," he admits. "It was meant to be a six month project, and now I've lost track of how many years it's been. It's something I work on in bursts and then burn out on and I need to go away and make something else before I come back to.

"Every time I come back I always think, Oh, what the hell was I worried about? This is actually a really good game. Because when you work on something you see all the rough edges - all the things that you need to fix. It can be easy to lose track of all the bits that are good. Then you get stuck in again and you focus on it and you burn on it and you fix little bits and pieces and then... Then you need to go do something else again."

It strikes me that Woods isn't so different from the average Captain Forever player, tumbling through space, building things, taking them apart, each time thinking: Is this it? How about this? He's launched himself into orbit, and now he just needs to go a little bit further. The Royal Air Force, rather fittingly, have a phrase for this sort of thing. Per ardua ad astra.

Through adversity to the stars.