Hate Plus review

Love takes time.

Christine Love makes games about sex and technology... sexnology games, if you will. They exist in a video game landscape that's saturated with objectified women, but rarely attempts to give women characters a voice for their own sexual desires. Her latest is Hate Plus, a follow-up to her last game Analogue: A Hate Story, both of which are about women characters' struggles to talk about their desires.

Analogue was a visual novel about cute girls in frilly dresses with kinky habits on a spaceship, thousands of years in the future. You were an archivist, digging into the ship's logs of a bygone Korean spacefaring society; your only company was two computer AIs who fought for control over you. Love deftly wove her warring AIs through the emotional revelations born of a patriarchal Joseon Dynasty of the future. That sounds like a sentence that would never describe a game, right? It's almost surreal to write it. But you'd need someone seriously well-read to pull it off. How deep is your Love? Pretty damned deep.

If you're interested in space soap opera twists and 'hacking' a terminal within a time limit, go and play Analogue: A Hate Story now. It's one of the finest, most unusual independent games we have. It asks you to become a critical reader of fragmented texts, a kinky word archaeologist who gets off on other people's perversions. It also has a quite admirable amount of sexy bits that made me feel like Alan Partridge at an orgy, and I'm no prude.

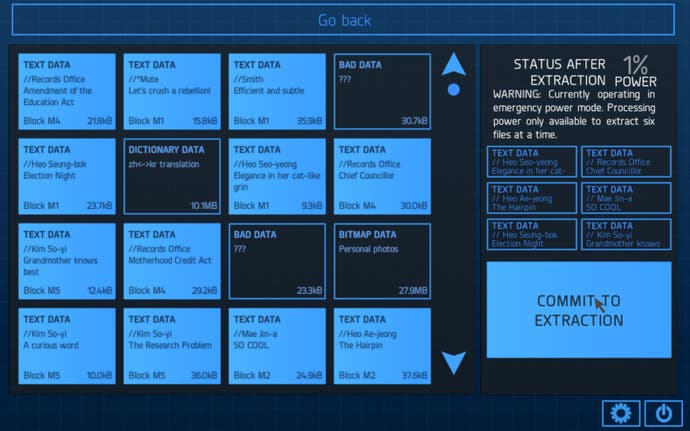

Hate Plus is an expansion-cum-epilogue to Analogue, and you can load your save from Analogue straight into Hate Plus to have the AI remember you (though you can also tell the 'computer' whether you fell in love with your AI, and designate a gendered or gender-neutral pronoun for yourself). I'm not sure playing Hate Plus without having played Analogue makes much sense, as it largely explores the events leading up to the creation of the society you explore in Analogue. You piece together the history of the characters' often scurrilous and manipulative relationships on board the ship Mugunghwa whilst forming a relationship with your AI. (Incidentally, you can change the AI's costumes throughout the game, my particular favourite being the Korean wedding dress.)

One of my favourite things about Love's work is that she can really work the visual novel engine, Ren-Py, by reconfiguring the original interface and how it looks and feels to scroll and play with. In Analogue: A Hate Story, you had a terminal window and a command line where you could type commands to the ship, including where energy was diverted to, or which AI was activated. This led to you playing the two AI characters off each other in an attempt to gain more access to the archives of the ship in a way that made you, the player, feel clever. It's hard to make anyone feel clever about their actions in games these days. Mass Effect hacking mini-games made me feel like a small child with one of those shape bricks you're supposed to put through the corresponding slot.

There were moments in Analogue when you felt like a 90s cyberpunk kid with neon fingerless gloves. You felt like that cursor was your needle of truth, and at one point, you had to tap commands in against a timer in a fevered panic. Sadly, Hate Plus has no such command line. But it does have your AI comment on the texts you unearth as you scroll, which is new, and it's more obvious when she wants to talk to you, which saves you time frustratedly clicking for more information when there is none.

Hate Plus is cosmetically prettier, and plays with real time. At the end of each part, in order to 'recharge' the ship's batteries which are running on emergency backup, you have to shut down the game and return 12 hours later. You'll need three real-time days to play this game. At first this seems like a tyrannical gimmick, as most games would use this as a cynical move to extend play time. But I started to realise that the game was attempting to seep into my actual life; when I started up to read again 12 hours later, I was refreshed and more interested in the archives again, and I was more receptive to chatting with my AI companion.

Later, there's a bit where your AI will ask you to bake a cake. No, actually bake a cake. Have you got the ingredients? Go and check your cupboards for them. Nope, you didn't take long enough checking for the ingredients, I can tell you didn't actually do it - and so on. The game timed my responses, eventually actually goading me into thinking I had to make a cake of some sort. You can send Love a picture of your real-life cake to gain a Steam achievement.

Christine Love is the closest we have to Margaret Atwood... Everything is done with a little feminist wink, rather than the usual video game sledgehammer

Here is my cake on the right. My friend Claire ate a bit of it.

It's an adorable joke, and yet the insistence on the player baking a cake is thematically and mechanically interesting. Within the context of video games, Christine Love is the closest we have to the author Margaret Atwood. Both writers touch on the themes of unreliable memories, the fallibility of people, gender relations. Is the often feminine-coded act of baking an attempt to bring the oppressive gender ideas of the Mugunghwa right into the player's reality? Is it an extension of the thematic emphasis on the fertility of women - that there should always be a 'bun in the oven', so to say? Perhaps it's just that Christine Love is being playful, finding ways to include her enthusiastic community? Everything is done with a little feminist wink, rather than the usual video game sledgehammer: Here is an ironic statement. Here is that ironic statement several more times.

There's a danger that you might think of Christine Love primarily as a storyteller rather than a game designer. Looking at Analogue: A Hate Story and Hate Plus together, the comparison reveals that she addresses the player's attention differently each time. Analogue is about the manipulation of people by painful social conventions - about outside influences playing people against each other. We are asked to choose our AI, manipulate that AI, whilst the story and the AIs manipulate us. We are a detective of other people's lives in Analogue.

Hate Plus also uses game mechanics to support the theme, but this time it's internal dilemmas, personal moral quandaries; you are a detective of yourself. Can you lie about making a cake? And then can you eat that cake? The mechanics of both games support their themes entirely. It's not an accident that Love makes you feel weird about lying to a game. Your personal values are the game.

All in all, the complexities of the Mugunghwa narrative are less structured in Hate Plus, and as a result the game carries less impact than Analogue did - but there's more fun to be had, more flippant drama. There's also less of the feeling that you're sneaking around, playing one character off another by opening up terminals and - hah - shutting the other AI down. There's less for you to input, but then Love plays with you more - like with the cake trick.

Does Hate Plus add anything to the original Analogue narrative? It does, but really it's less of an epic and more of a sexed-up frolic through the ideas and characters presented by the previous game. There's definitely more sex, and Hate Plus has added useful visual cues: when you click on the name of a character you will see a portrait of them, which makes the Korean names less daunting to remember, and who is bonking who easier to figure out. The AI *Mute has become a perfect, Metal Gear Solid-style eyepatch badass, though her personality is somewhat more bubbly in Hate Plus than you'd ever expect.

As usual, Love's eye for a scandalous and knowing wink at gender relations forms an enjoyable, coherent journey through well-rounded characters' lives. If Hate Plus has a downside, it's that you will have to put aside time to read things for three days. But the upside is that you get to read Christine Love's stories for three days, have your cake, and eat it as well.