The Stanley Parable review

I would prefer not to.

It starts with the modern hall of mirrors - a screen depicting a screen depicting a screen. I can count three of these before the detailing gets too small to make out, but even then I'm forgetting one. I'm forgetting the crucial one, in fact: my own screen that depicts the first of the virtual screens. And moving out beyond that?

The Stanley Parable is a video game that plays you. It examines questions of control and free will within a finite interactive space and asks: can you truly express yourself in a world in which an omniscient designer has already carved out all of your possibilities in advance? Is there real victory to be won inside a machine that has been pre-programmed to deliver victory to you anyway? None of this makes The Stanley Parable sound like an enormous amount of fun, perhaps, but the whole thing's also hilarious and ingenious and even quietly disturbing at times. It's a game about games, yet it never forgets to be a game that's worth playing in its own right.

Davey Wreden created the original version as a Source mod that was released in 2011. Since then, he's been rebuilding it - and reimagining it - with designer WIlliam Pugh. The end result is not quite a straightforward remake. The story still revolves around Stanley, who toils deep inside an office complex where the staff are referred to by three digit numbers like Peugeots, and it still concerns a strange event in which all of Stanley's colleagues go missing, but the plot's branching paths have been tweaked and amended here and there, and entirely new options have been added throughout.

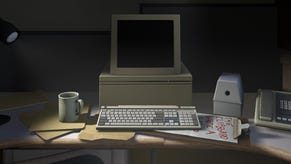

As it's no longer built from Half-Life 2 textures and assets, the game's ditched the incongruous air of derelict Euro-prison chic and embraced a more fitting environment for its tales - the darkly prosaic world of modern bureaucracy. Stanley doesn't tap away at a weird, insectoid Combine terminal all day anymore, he sits in front of a CRT display with a green screen and a flashing cursor. Equally, the void of his emotional life is invoked not through scarred concrete floors and walls painted a peculiarly institutional beige, but by a discarded electric pencil sharpener, naff corporate escape art, and a coffee mug denouncing Mondays. It's The Office, starring Bartleby the Scrivener rather than David Brent.

The meat of the game continues to lie with the narrator, though, an avuncular English voice that leads Stanley from his desk and out into the world, and who defines The Stanley Parable as you either obey his orders and tag along, headed towards the most arch and self-cancelling of victories - "Stanley would never again follow someone else's orders without question!" - or attempt to confound him at every turn, taking the right door when the left is proffered, going downstairs when he calmly declares you have gone upstairs, or hiding in a broom closet.

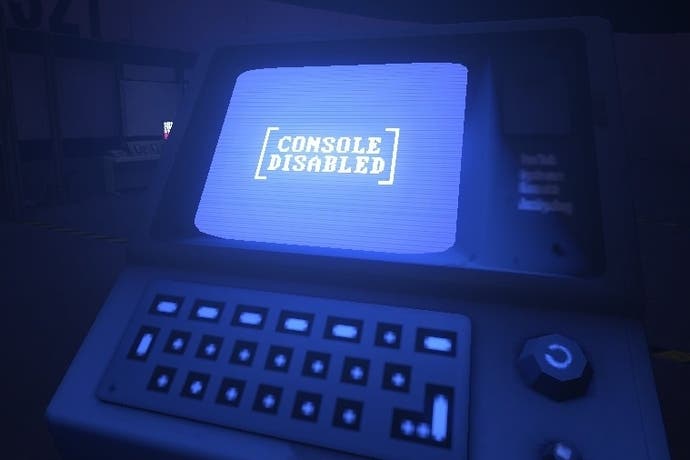

Whatever you do, though, the kicker is that the designers have gotten there first. Your most transgressive choice - even, crucially, the choice to do nothing at all - is met with the game's familiar biting retort: more content. Jokes, jibes, special effects, The Stanley Parable has foreseen everything. At his worst - or perhaps best - the narrator lets you roam free for a minute or so and then crops up suddenly, predicting with worrying accuracy just what you've been up to while he was silent. Are we all so predictable? So controlled?

Throughout all this, there's still plenty to surprise seasoned Stanleyphiles. The game's narrative and thematic preoccupations remain the same, but the settings are grander, the alternate endings more elaborate. Sometimes a difference is trivial or purely cinematic - the boss's office has grown an executive toilet, for example, while a surveillance room that was once home to dozens of monitors now has hundreds. On more than one occasion, however, you're in for something much more elaborate: a glorious rebuilding of the landscape around you as you follow trails, hammer at buttons, and watch the office warp about and even erase itself. Reaching some of the more convoluted endings is like being on a Möbius strip made of file cabinets and tile carpeting. You'll find yourself exploring the least likely of treats, too - how did that wind up in here?.

However you tackle these sights, the game wants you to disobey - disobeying is just another form of playing along, after all. Beyond that, the deeper joke is that the various conclusions you're tracking down allow you to play The Stanley Parable as a fairly traditional objective-based video game in its own right. Hunt down the multiple endings! Gotta catch 'em all.

Meanwhile, the narrator's spiel continues throughout, quietly earning a place alongside GLaDOS or Mark Hamill's Joker in the pantheon of great video game taunters. Comforting, cajoling, spiteful and frightened, the narrator's as much a pawn as you are, even if he often seems to be the Jeeves of your own personal Hell.

Familiar but consistently surprising, this new Parable even fits beautifully into the existing game - a game that took its power not from a single narrative but the interaction of all its possible narratives, super-positioned and entangled. Here is another suite of variations, another arrangement of false choices to consider. I'm heading back in now, actually, looking for a door - I'm sure it'll be a door - that will hopefully lead me from the new build and into the original 2011 code. There, amongst the Source engine's grubby Half-Life 2 assets, is where my parable will end. That is where Stanley and I will find closure.