Tropico retrospective

Banana skint.

The things I've achieved in strategy games. In Civilization, I founded the UN, cured cancer and went to Alpha Centauri. In Age of Empires, I developed a group of nomad settlers into a vast, militarised Iron Age society and conquered the world. And in Tropico... Well, I was ousted after 30 years, leaving only my legacy of decreasing pollution by 15 per cent.

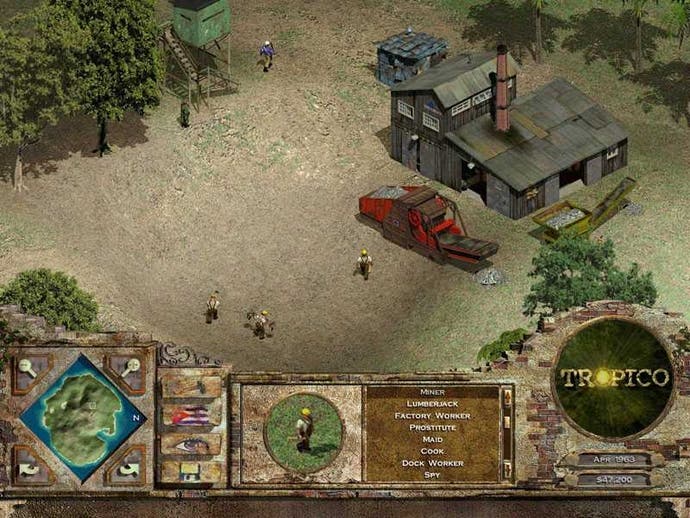

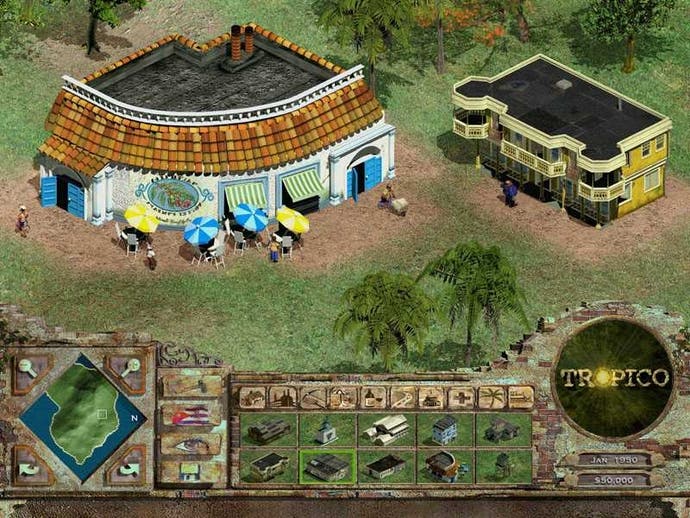

Tropico, created in 2001 by the now defunct PopTop Software, isn't like other strategy games. Set against the backdrop of the Cold War, it puts you in charge of a small banana republic - the eponymous Tropico - and leaves you to deal with things like tax rates, building permits and workers' rights. There are no options to build tanks, no impressive buildings like Stonehenge or the Tesla Coil. Instead, you essentially play the role of a local councillor or town alderman.

You're not a supreme ruler. If you want to build a college, you need to clear it with the ministers. If you want to increase working hours, you should expect resistance from the unions. And so, any positive change you make to Tropico, no matter how small, feels like an enormous victory. I spent 10 years negotiating a construction discount with the Russians just so I could afford a slum block of tenements. I was 15 years in power before the island even had electricity. Every political decision you make leads to backlash from your electorate. It's such a difficult game.

It could be seen as frustrating. The systems that govern Tropico aren't particularly visible. It's not based on typical video game logic, which says every time you press button X, it will have result Y. The needs of your public are fluid; they change constantly. Sometimes, extending working hours will give you an inexplicable ratings boost. Other times, improving healthcare will, for some reason, cheese everybody off. Tropico simulates the part of a politician's life that has every decision they make resulting in someone, somewhere calling them a tit. You can't win.

But although that can be infuriating, it seems to me like that's the point. The later Tropico games, particularly Tropico 3, devolved into this awful, unfunny, Grand Theft Auto-style satire, where every joke is delivered out loud and it's all very obvious. There's this news bulletin in Tropico 3 about a llama that's stolen the president's hat and is now going to be executed by firing squad. It's forced and, quite honestly, rubbish. In the original Tropico, though, the satire is razor sharp.

It all emanates from that difficult to predict, impossible to master gameplay, whereby no matter what you do, you never seem to make progress. I'm in a game of Tropico and 80 percent of my citizens are living below the poverty line. So I start building more farms. Then I get a letter from the ministers saying Tropico needs a church. Since most people on Tropico are religious, I decide to cancel two farms and build a church. Then another letter: we want a cathedral. Again, I can see my ratings slipping if I don't oblige so, with heavy heart, I cancel all my farms and build a cathedral. Two months go by, the election comes up and I lose because no-one has any food. I jump up and yell "you people don't know what you want!" And this, I imagine, is how any government must feel.

The other games in the Tropico series poke fun at the president. It's all jokes about how El Presidente is corrupt and insane and ineffective. Those games have the same political mentality as a cab driver - whatever is going wrong with the country, it's the fault of whoever's in charge. But the original is more interesting. Your people really don't know what's best for them. You sit there, looking at reports from your ministers, at last year's crime statistics and at next year's budget and you know that what your country really needs right now is a better hospital. But your people want a new leisure centre. They don't understand and don't care about the bigger picture - they just want what they want. It's a political commentary that not only have I never seen explored in other video games, but rarely see in other media full-stop. We don't like to criticise The People. The People are always good folk, with common sense, who are being shat on by higher-ups. You'll never see a politician say, "I told you so."

But Tropico does. It's a satire, less on politicians themselves, and more on the compromises they have to make at the whims of their constituents. You go into the game with all these lofty plans but soon find yourself bending to every demographic on the island on the off chance that they might let you stay in power long enough to achieve just one thing of your own. For 25 years I ate crap from the unions, the communists, the military and the farmers. It was only in the last five years when I was able to push through anti-litter ordinance and switch the power stations from coal to gas. And then, while they were all still living in shacks, propped up next to their giant leisure centre and three churches, they voted me out.

And Tropico isn't just brave political satire. It's progressive - it was way ahead of its time. Here you are, this supposed ruler of an island, but you're not the one who's really in charge. You're disempowered. Every decision you make will, eventually, come back to bite you. Those are themes that video games have really only started to explore recently. If you think of things like Spec Ops: The Line or The Walking Dead, they turn the player's agency back on itself. In Spec Ops, you end up killing more people than you save. In The Walking Dead, no matter what you do, your friends die.

And in Tropico, the more you try to change things, the more they stay the same. When you start, the people are unhappy because there's no food and nowhere to live. When you finish, the people are just as unhappy. The only difference is that now, instead of bad food, it's because the casinos are too expensive and the hospitals are crowded. You're meant to be El Presidente, but you can't change anything. Tropico is now 12 years old, but even by today's standards it feels thematically fresh.

Since forever, strategy games have been about growth, expansion and power. They're the ultimate exercise in player agency, as you watch your small, provincial township grow into a full-sized empire. But not Tropico. Tropico is about attrition and red tape and compromise. In the face of complex and ever-changing circumstances, it's about doing whatever small amount of good you can. Not only does it satirise the deadlock of real-world politics, where Congress blocks legislation and the electorate makes demands, it plays on our ideas of video game empowerment. Decisions are made for you in Tropico - and it's one of those rare, interesting games where trying to play the right way doesn't always bring you the best results.

Tropico perhaps did for strategy games what Spec Ops did for military shooters - and it's only now, 12 years later when discussions about agency are starting to be held, that you can appreciate Tropico in full. If you haven't played it, go play it. If you have played then, well, I'll feel for you - because more than any other game, in Tropico life at the top is hard.