Games of the Generation: Portal

This was a triumph.

Over the next two weeks we'll bringing you our pick of the games of the generation - and today we're starting off with Portal, Valve's exceptionally smart puzzler that was the surprise highlight of The Orange Box when it launched in October 2007.

Few would dispute that, when it comes to video games, this has been the decade of the shooter. Endless racks of guns have passed through our fingers, some based on pristine real world counterparts (Call of Duty, Battlefield), others rickety and unreliable (Far Cry 2), yet more futuristic or fantastical (Halo, Mass Effect). So much effort and iteration has gone into the virtual gun (the way that it bobs in the hand, its irritable kickback when fired, its vocal performance), that this year Infinity Ward - architect of the contemporary shooter in Modern Warfare - resorted to dented sights as notable feature in its next Call of Duty game. It's understandable: once you've delivered perfection where else to go but imperfection?

The gun suits the 3D video game like none other of our species' inventions. There is no tool better suited to giving players the ability to affect objects both near and far in a 3D world, extending the player's reach into the television screen. With a bullet we can take out an enemy standing directly in front of us or just as easily shoot a wall-mounted switch a hundred metres into the distance. Change the breed of gun and you alter a game's entire pace and rhythm, from the slow buckshot suckerpunch of the shotgun to the pitter-patter niggling of a machine gun. What other invention offers the player such scope, flexibility and utility? For this reason the gun has been promoted to a position of ultimate importance in blockbuster video game land. Indeed, viewed with fresh eyes it can look like our medium builds its worlds around the gun, which nods proudly front and centre screen.

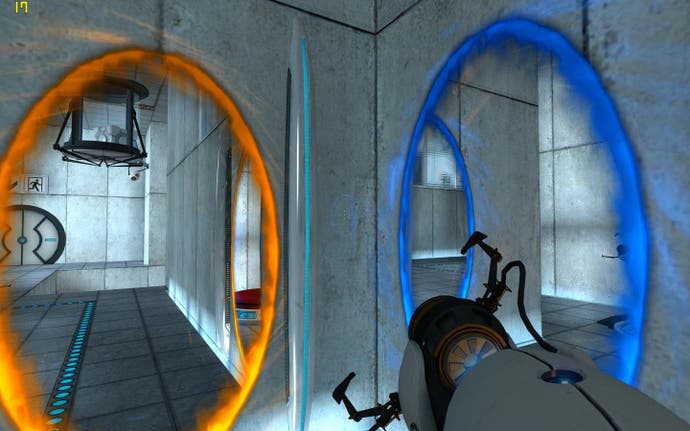

Portal is a game built around a gun. Its levels are an extension of the weapon (known as the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device) that its mute protagonist, Chell, grips, their shape and contour defined by its abilities. Remove the weapon and this world no longer makes sense, or is even navigable. It is a game that only the Portal gun can unlock.

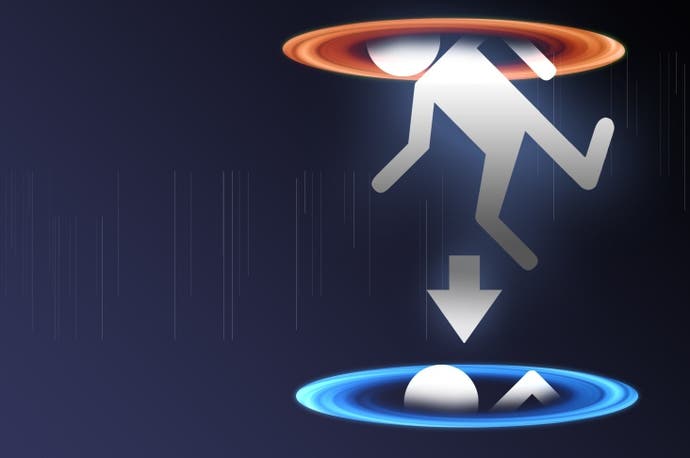

And yet, Portal is also the most subversive first person shooter yet made, despite the fact it converses in much the same vocabulary as Call of Duty and its cloud of imitators. Why? Because the Portal gun doesn't fire bullets. Shoot the gun's projectile against a flat surface and you'll open an oval portal door. Shoot a second portal somewhere else in the environment and stepping into one will see Chell emerge from the other. Portal's gun cannot wound and it cannot kill: all it can do is create an exit, an exit that leads away from violence, an exit that leads away from cliché.

Gordon Freeman, the protagonist of Half-Life, the grand first person shooter fantasy in whose underground belly Portal takes place, is the game designer personified as the hero. Bearded and studious, with thick glasses and geek-chic ruffled hair, Freeman is the arch nerd who's stepped from the confines of the computer lab to take on the jock power systems outside. But in Portal we see the personification of a different side to the game designer. GLaDOS, the female AI who guides Chell through a series of 19 tests is the arrogant bully game designer, who teases and mocks the player as they quest through her pre-set puzzles. She lures you through her game, repeating the promise of cake for the successful completion of her set of errands, her tone flitting treacherously between encouragement and cruelty, eventually revealing a sadistic thrill in seeing her player suffer and fail.

You obey, even as GLaDOS shifts in character from kindly guide to abusive tormentor, solving her tests and challenges, attempting to, as GLaDOSs herself remarks "remain resolute in an atmosphere of extreme pessimism". We're used to this sort of thing, of meeting a designer's cruelty with resolution, and the game within a game reflects this relationship between player and designer with sharp insight. But the game's subversion with its tools is later reflected in the game's broader structure. As GLaDOS' vindictiveness is revealed, so you start to turn your weapon against the system, using it to puncture the Apeture Test Facility's artifice and slip behind the pristine scenery, where you are able to view the ropes and pulleys that fire the game, those nooks where the dust accumulates and spiders preen.

The act of turning your gun against the system that created it is further reflected in your later interactions with the game. A furious GLaDOS sends turrets to destroy you (the only time that the sound and fury of bullets fills the air). But there is no way to shoot back; the Portal gun is a passive tool, unable to injure. Your only choice is to turn the violence back against its perpetrators, as you create a portal through which their bullets pass, and another that sends them right back towards them.

This has been the decade of the shooter, of male fantasies in which erect barrels extend from the player into the centre of the television screen, spitting power and dominance with each squeeze of the hand. Our games have been about an escalation in ability; experience points funnelled into making our characters harder, better, stronger, faster, each new stage unlocking more effective ways to beat our opponents. Portal has none of that. In this game you remain weak and helpless throughout - at least in terms of raw power.

In a game in which your only abilities are to jump and create rips in space, cunning and ingenuity are your only tools to progress. It is no accident that, aside from the bullet-spraying turrets, Portal presents an all-female cast. In this way story and theme are fully aligned: a game that subvert the systems of a genre, the systems of an entire medium and, in its occasional anarchic moments, the systems of power and government (note the achievement awarded for destroying every one of the CCTV cameras bolted onto Aperture's eavesdropping walls).

Released in 2007, Portal was met with unanimous, sustained praise and yet its influence has been almost non-existent. There have been no imitators, no cover versions, no respectful nods from other studios hoping to build upon its lessons and approach. That is, arguably, because it is a complete game, in which story and mechanics elegantly entwine and unfurl towards their natural conclusion. Like a short story that is too rounded to expand into a novel, and too idiosyncratic to birth a genre, Portal sits alone, majestic. It's a game that offered an exit from a cliché, but one through which only it seemed to fit.

Even the sequel, for all its cleverness and expansion, was unable to match its perfectly told story. In video games we are led to believe that a debut is a first swing: sequels, being technological evolutions as much as creative ones, will always curve towards improvement. Portal refuses to adhere to this rule, just as it rebukes the rest of them. It's proof that once you've delivered perfection where else is left to go but imperfection?