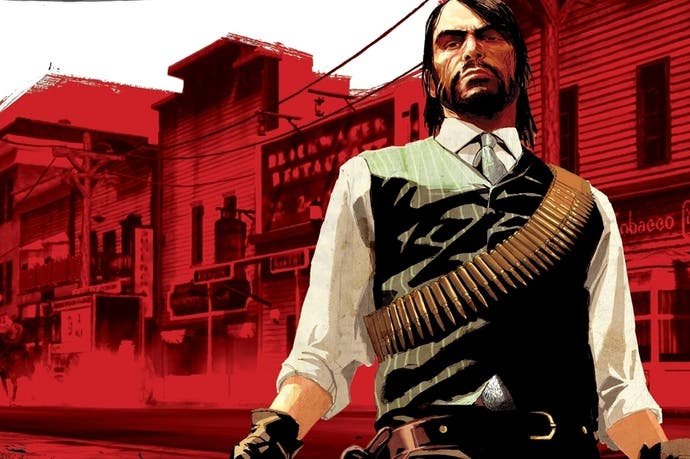

Games of the Generation: Red Dead Redemption

How the purple mountain majesty of Rockstar's western epic showcases open world gaming at its best.

Over the next two weeks we'll be bringing you our pick of the games of the generation. Today we're looking at Red Dead Redemption, Rockstar's western that provided a surprisingly sombre take on the open world genre when it launched in May 2010.

Free roaming games weren't invented during this hardware generation, but they certainly came of age thanks to the increased processing power that the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 offered. It's an evolution that reached its peak with Grand Theft Auto 5, a staggering technical achievement that conjured a living, breathing city and its surrounding landscape from mere ones and zeroes.

Yet when I look back over the last eight years, it's not Rockstar's urban crime opus that resonates most strongly. It's Red Dead Redemption, the developer's western spin on the genre they popularised.

Certainly, before the game's release in 2010, it was considered more with curiosity than anticipation. A sequel to an abandoned Capcom shooter, resurrected by Rockstar six years earlier to little acclaim, it seemed an unlikely follow-up to the success of Grand Theft Auto 4, and inevitably spawned lots of Grand Theft Horses jokes.

The reason it's stayed with me all this time, and the reason it was the first game that popped into my head when the topic of the best games of the generation came up, is because it's the first and, for my money, still the only Rockstar game to truly deliver on the freedom suggested by the open world formula. It's a game of wide open spaces, a big brush canvas that has the balls to leave the player to explore without filling up the map with too many "to do" icons.

The stroke of genius is in the setting. The Old West is an era when the friction between content and context makes perfect sense. Every time you wrack up a huge body count in GTA, the sort of slaughter that would dominate headlines for weeks in reality, and then snap back into the prescribed narrative without consequence, the painstaking immersion of the city takes a beating. It's revealed as a playground, where the rules constantly bend to accommodate you.

Out on the frontier, where the law still struggles to make its mark, you can gun a man down in the street and it enhances the fiction, powered as it is by iconic images of John Wayne and Clint Eastwood, rather than undermining it. There's a romance here that is lacking in modern day open world games. Whether you choose to play John as an honourable man trying to redeem his past, or as a scurrilous outlaw cashing in on his fearsome reputation, it all fits into a western archetype.

Rockstar could have got away with simply choosing a generic Wild West theme, swapping cars for horses, gangsters for bandits, and Red Dead Redemption would still have been a fine game. But they dug deeper. Setting the game in 1911 rather than the 1800s gives John Marston's quest for revenge real meaning, real resonance. In a game in which death constantly looms large, the most tragic demise is that of the frontier itself as automation encroaches into its wide open natural spaces.

"Red Dead Redemption knew the value of emptiness, of silence, of space. It had confidence enough in its players ability to engage with the fiction that it could create a beautiful landscape and not clutter it up with crap."

The fact that the game climaxes in the town of Blackwater, with its neatly lined streets and advertising slogans painted on buildings, is devastating. Staring gentrification in the face, Marston literally looks like a man out of time, and the hours you spent travelling across untamed landscapes are thrown into sharp relief. It's not just John whose days are numbered - his whole world is literally coming to an end. Within ten years, Blackwater will be everywhere.

That sort of sweeping melancholy tone is an ambitious undertaking for a medium that is more comfortable with simple acts of violence, and Red Dead Redemption doesn't always work, of course. The section of the story set in Mexico trips over the old hurdle of forcing the player down fixed paths, insisting you play both sides of a simplistically rendered conflict, and refusing to progress the story until you oblige. Nor is it the most graceful game, with a sticky cover system and sometimes awkward movement. Getting Marston through a simple door can feel like threading a needle underwater while wearing boxing gloves.

It's notable, I think, that years later the details of the story have become murky and the frustration of those technical wrinkles has receded. Not that the story wasn't well told, but that the fixed points it added to my adventure have now served their purpose and can slip away. What remains are the moments that are uniquely mine, more like sense memories, an almost physical recollection of what it feels like to gallop to meet the dawn on the prairie, and to welcome dusk in the mountains by the glow of a campfire.

These aren't abstract external memories. These are internal - things I did, things I experienced. It's this lingering phantom sensation of having tangible memories of an entirely virtual place that is the true power of an open world. It's also a power that has been increasingly abused by games that see an empty space and feel compelled to fill it with stuff. Not necessarily anything important or fun - just stuff.

For me, the thing that sums up the worst of this hardware generation's often grotesque bloat is a quote from John Teti's masterful review of Assassin's Creed 3 over at Gameological. "Perhaps you'll gather lumber and make a barrel," he wrote of the sheer mind-numbing amount of superfluous systems churning in the guts of Ubisoft's blockbuster. "Congratulations, you now have a barrel."

Red Dead Redemption was, for me, the last of the open world games to avoid that trap. Yes, there's stuff to do away from the missions, but it all fed into the romantic fantasy we were being invited to indulge. Bringing in wanted men, dead or alive. Hunting in the wilderness. They were all aspects of the gunslinger myth. It never assumed that we'd want to get into the barrel making business.

If asked to boil down what makes Red Dead Redemption my favourite game of the generation, it'd would be this: it knew the value of emptiness, of silence, of space. It had confidence enough in its players ability to engage with the fiction that it could create a beautiful landscape and not clutter it up with crap. It saved its bullet points for the bodies of bad men lying in the dust, not for a press release, and in doing so offered the most singularly absorbing opportunity to live a different life that these consoles offered.

To walk in the bootprints of Ford and Leone, not to read, or to watch, but to feel history shift beneath our feet as an old world was ground away by the new, if only for a short time. Hopefully the next console generation will offer similarly powerful experiences, or we'll be destined to make more barrels than memories.