DoDonPachi retrospective

The full extent of the Jam.

If the bullet hell shooter has a poster-child, it is arguably Ikaruga. Treasure's elegant masterwork is repeatedly thrust to the front of the shmup crowd, pushed into the limelight to be applauded by the mainstream as the ultimate example of its genre.

The 2001 arcade release is unquestionably a heavyweight among its contemporaries - to claim otherwise would be to disregard both its popularity and its impact as an ambassador for 2D shooters - but Treasure's creation is not the most typical or influential example of its form. In fact, its graceful pace and hints at puzzle game design make Ikaruga somewhat distinct in a genre defined by more aggressive works.

Which is where the DonPachi series steps in. Developed by Cave, the original 1995 release of DonPachi is clattering heavy metal to Ikaruga's operatic sophistication. And while Treasure's creation dazzles under the public glare, the DonPachi games serve as a true standard bearer for the shmup genre's famously devoted fanbase. Without doubt, even in that clique Ikaruga is highly regarded, but it is DonPachi and its canon descendants that continue to attract the most high-scoreboard activity, each standing as a keystones in almost two decades of the 2D shooter's evolution. More specifically, it is the second game in the DonPachi series, 1997's DoDonPachi, that is the seminal goliath of a genre founded in Japan's arcades.

For those who need reminding, Cave is the foremost developer of bullet hell shmups, referred to variously as danmaku or manic shooters. Its games are remarkably difficult and highly desirable, with some examples effortlessly cruising into four-figure price territory on the collector market. Founded in 1994, Cave lead a charge to establish a new template for the arcade shmup; delivering titles that spew forth elaborate, densely packed formations of garishly coloured bullets, veiling intricate scoring mechanics with deceptively simple gameplay.

For as long as there has been Cave, there have been the DonPachi games. Cave itself was formed after the demise of Toaplan, an influential shmup studio behind titles like Truxton, Fireshark and Zero Wing, the latter of which brought the world the meme 'all your base are belong to us'. Come 1994, all was not well for Toaplan. The studio collapsed, prompting former staff to gather around spin out studios. Gazelle, Raizing, Takumi and Cave threw open their doors, each devoting itself to continuing Toaplan's legacy, building on the concepts from the studio's late 1993 release Batsugun, an early example of true-bullet hell, and a genetic prototype for some of the world's most demanding games.

One of the former Toaplan staff was a talented programmer named Tsuneki Ikeda, who, after just two years with the now-defunct studio, co-founded Cave with, among others, Kenichi Takano, who would stand as the start-up's chairman. It was June 1994, and with their new team, it was decided that Cave would try and ape the style of Toaplan's latest works, while developing a new arcade hardware system. The result was DonPachi, released to arcades in 1995 on a slab of circuitry and chips now most commonly found wrapped in anti-static bubble wrap in collectors' vaults; namely Cave's 68000 PCB.

Back then it was slotted into JAMMA format arcade cabinets and established the series' core scoring mechanics, which centred on a combo meter that rewarded players for consistency of play style. Moreover, it remoulded the Batsugun template, resulting in a swifter, more challenging game.

But Ikeda perceived that DonPachi was a creative failure. In his mind it didn't capture the spirit of Toaplan, much to his disappointment. The fact he had made a game so admired it is still played today didn't matter to a famously self-critical creator without the benefit of hindsight.

What he did next, however, was take a bold step that would establish Cave as the leading post-Toaplan studio and change the scrolling shooter forever. Ikeda joined forces with Satoshi Kouyama, Makoto Watanabe and others to plan, program and produce Cave's next game, DoDonPachi, which also ran on the 68000 system. Calling on an old friend from Toaplan, Ikeda secured Gazelle's artist and designer Junya Inoue, better known as Joker JUN, to work on the project.

But rather than retreat back to Batsugun, the team concentrated on what made DonPachi distinct. Coders wrung more bullets from their code, chiselled the hitbox away to a cluster of pixels, and fattened the soundtrack with weightier guitar sounds. Cave was no longer trying to imitate Toaplan. Instead, it was trumping its forbearer.

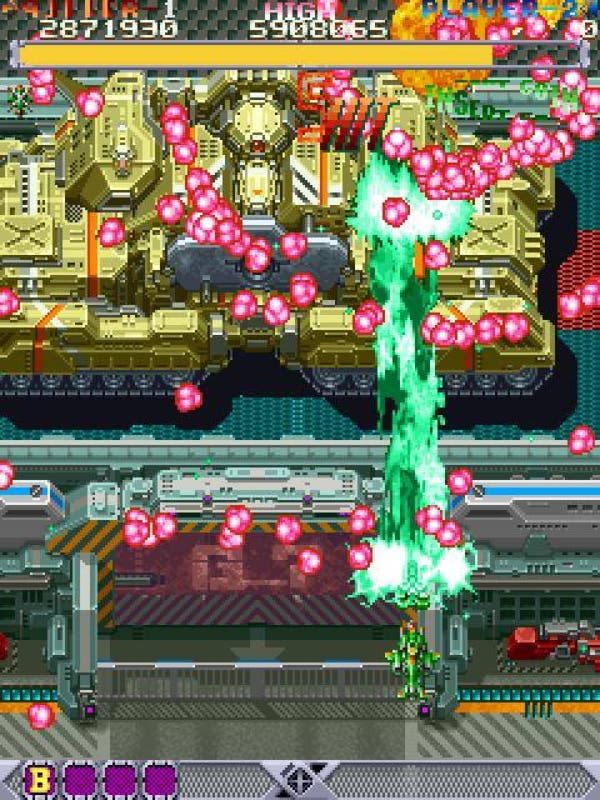

As such, everything about DoDonpachi pummels the player. It leaves no space for the solemn grandstanding seen in other examples from the same year, such as Square's Einhander. Bullet patterns whip back and forth, intersecting to create a writhing maze in neon pixels. Enemies large and small tumble onscreen, demanding the player make remarkably precise, minute movements under great pressure. As with any shmup, to play DoDonPachi properly is to play for score, which means manipulating a combo system that can frustrate almost more than it can reward.

DodonPachi rarely lets up. It isn't concerned with capturing the majesty of space and the wonders of the universe. It is a game about conflict and war, and it makes no attempt to romanticise either. Even the narrative is unsettling; a misanthropic tale of conflict and suffering the human condition. DoDonPachi boasts a two-loop structure. Scrape through its six levels in a single credit, and the game concludes without much more than a quick thank you by the commander of the DonPachi Corps elite fighting force.

Clear the stages with near-perfection, however, and DoDonPachi starts at the beginning again, with the already fierce difficulty ramped up to the point of feeling impossible. The second loop doesn't just hand out punishment to the player; it delivers some brutal context to the action, as it emerges that in the first cycle of the game you have been gunning down friends and comrades, each aware that you are the unknowing puppet of your own commander, a megalomaniac madman set on eradicating humanity due to his belief that the species' is a flawed creation. It's a theme explored throughout the series, and a stern nod in recognition of the fact that, albeit through layers of abstraction, shmups are remarkably violent games.

Elsewhere, even the title screen is a brutish thing, rasping the game's name - both an onomatopoeic allusion to gunfire and a shout out to the bees that are the series' central motif - like a cacophony of unruly jackhammers.

But why all the difficulty? Why assault the player and toy with their nerves? What motivated Cave to conceive a game so unkind to the senses? It all goes back to Toaplan, and the studios that formed from its demise. Cave, Gazelle, Takumi and Raizing - also known as 8ing - watched one another closely as they strove to define the future of shooting games. In 1996 Raizing released Battle Garrega, which has such complex systems at its core it remains a subject of much admiration and strategic analysis within today's shmup player community.

While the original DonPachi had hinted at how the Toaplan design template could be reworked, Battle Garegga had stamped all over it and rebuilt it from the fragments. There were more bullets and more demands on players, who were relishing meeting the challenge. Raizing had set the benchmark in the race to fill Toaplan's shoes, and Ikeda was hungry to wrangle that lead from his former colleagues. He claims he thought it impossible to trump Garegga, but still he counted its bullets. Was that 60 on screen at once? Then DoDonPachi better have 100. And at the end of the second loop, with true last boss Hibachi, why not 245 bullets on screen? Raizing might not meant to have issued a challenge, but Cave stepped up anyway, and so it was that intensity was the ultimate design objective for those creating new shooters.

The game's unrelenting nature may also have something to do with what it meant to Ikeda, who confirmed in an interview for Cave's official 2010 Shooting History book that if DoDonPachi did not sell well, he would quit the games industry. He had to give it his all, and the result was a game that outdid all that went before it.

It's a tradition that continues to this day. A new bullet hell arcade shmup worth its salt must strive to outdo the competition in terms of what it throws at the player, and in that regard, the DonPachi series remains a contender. Aside from a peculiar hardware deal that saw another studio develop the less than astounding DonDonPachi 2, and a clutch of mobile releases conceived for a wider pool of player abilities, the DoDonPachi games have generally been champions of intense arcade gaming.

The series has effectively reached its conclusion with the 2012 arcade release of DoDonPachi SaiDaiOuJou. Commonly known as SDOJ, it amplifies everything about DoDonPachi. It is harder, faster and more complex than any other instalment. Take a glance at 2013's Xbox 360 port and you'll see that it is brimming with multipliers, rank meters and other trimmings of the genre. SDOJ is a sadomasochist's piñata in digital form - it pours out numbers, symbols and tokens as it is beaten, and it's there to thrill, frustrate and, if you stick with it long enough, reward.

Still, it is the 1997 DoDonPachi that is the series' true star, and a game that deserves to be Ikaruga's dancing partner as it sparkles in that limelight.