The write stuff: Elegy for a Dead World preview

The game that you play by writing about it.

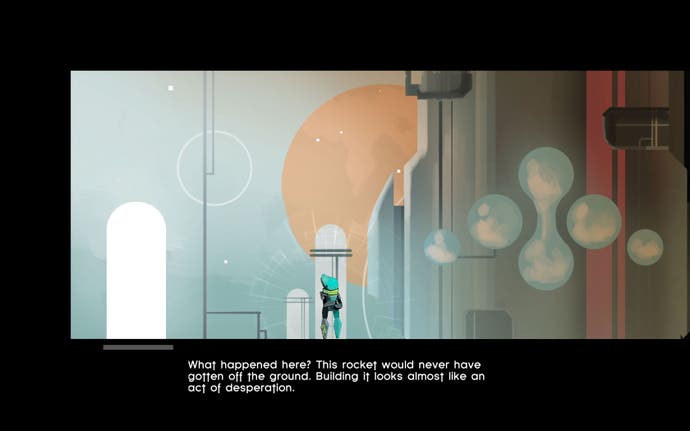

Dejobaan Games and Popcannibal's upcoming experimental game Elegy for a Dead World wants you to write. Part video game, part creative writing exercise and part sociological experiment, Elegy casts players as a wandering scribe exploring the remnants of three lost civilisations. There's no combat, puzzles, or obstacles of any sort. The challenge then, is to interpret what happened and string together the most poetic prose you can for others to rate on Steam Workshop.

Yes, Elegy for a Dead World expects you to work. And not the sort of ways games usually ask you to work, by fulfilling rote fetch quests, managing your virtual farm, or eradicating an open world of thugs; it expects you to actually wrack your noggin's vocab to sling together a gripping yarn. Saving the world is easy - writing, however, is hard.

Of course, anyone can write about any video game. Just Google fan fiction for Mass Effect or Resident Evil (or better yet, don't). What makes Elegy so special is that it actually incorporates this meta game into the game itself by giving the player a journal and encouraging them to take notes. By the time they've finished wandering the world, they'll have a full piece of literature which they can then edit before exposing it for all the world to see.

Incorporating the journal into the game world is vastly important. "There's this weird intimacy that we're generating with this landscape," co-creator Ziba Scott (of Popcannibal) explains to me over Skype. "It's one lone character wandering around this empty place. It makes you feel like there's no one around and I can admit things. I can be truthful here. When, in fact, you're talking to the internet."

Scott stresses that he aims to put players "in the mood to be in this fiction and be a part of it, versus giving you proper word processing tools, which is not sexy and not inspiring... We had to find this balance that would get you excited to write for a short period of time."

In fact, the game casts you into one of three roles simply to give players a frame of mind from which to enter what could otherwise be a daunting undertaking. Upon entering a world, you're given a choice of what to write: "A scientific journal," "their story," or "my story."

Practically speaking, it doesn't matter what you pick. You'll still explore the same three worlds - each inspired by the works of a British romantic poet (Shelley, Byron and Keats) - and you'll encounter the same observations and prompts. The only difference is the mindset you're in as you digest the ruinous landscape and filter it into words.

"As important as what they see when they take a role is is the mindset we're trying to put them in," Scott explains. "What we're trying to do is motivate people so they get into a mindset where they have something they want to put out and write. We found just dropping them into a blank slate is too much. It's intimidating. The roles are about giving them something to play as; to set the stage for their writing."

Players are also given visual feedback in the form of a radial pattern around their avatar to stress how much they've written. While there's no word count requirement, this operates as a way to nudge players into writing more.

Whether it's the visual feedback or not, people are taking to it. "Based on what we've seen so far I will not be surprised if we get an entire novel as one of these stories," hypothesised Dejobaan CEO Ichiro Lambe. "People love being creative and I don't think there are many games that are conducive to this kind of creativity.... I bet we'll get a novella-length thing within a couple months of launch."

While Elegy strays about as far from the concept of a game as possible, there is one game-y aspect the developers are integrating. "One of the things I'm excited about is the idea of an achievement, which is a very gamey concept, for having writing that other people appreciate," Scott says. "In some ways it's not even a game. We're actually rewarding an achievement that has real merit and value, that actually has some significance that you should be proud of."

There's also some risk involved in acquiring the achievement, because you're fundamentally opening yourself up to the mercy of the internet, a virtual realm where many of people's worst qualities come out. "When I read people's stories I feel like I'm intruding on them," Lambe admits. "It almost feels like a very personal thing that I'm playing voyeur at. I've had the experience of actually having an emotional reaction to that."

As any writer will tell you, submitting anything to anyone is hard. What will they think of your work? What will they think of you? Will you have an embarrassing typo? When asked if players will be able to alter their work once submitted Scott replies, "I do have some concerns about that, of course, like if someone writes a stellar entry and then changes it to the word 'poop' over and over," he laughs, "but It becomes sort of a public performance... You're asking people for a very personal and very tender thing - to say 'please give and please put out and share with people'. I'd like to find ways to make that less scary, of not having this permanence of submit now and forever. I'd like it to be a more mobile thing."

Thankfully, the devs have been pleased with the stories that have emitted from Elegy's prototype. Lambe said of one of his favourites, "They wrote this loving, lavish description of who this civilisation was and why they thought it was this way. So they took all the visual and contextual elements, digested it and turned it into almost like an anthropologist's narrative of the world... It was about 50 per cent congruent with what we'd intended when we created the worlds, so that was interesting because the author got that much, but went in a completely different direction for parts as well."

This isn't to suggest that authorial intent matters for this sort of project. While Lambe, Scott and artist Luigi Guatieri might have a specific story in mind, it's purposefully open to interpretations and the community of scribes has taken full advantage of this freedom.

Scott explained that the team discovered early on the beauty of leaving things open-ended when they showed a rough prototype of one of the worlds to a friend of theirs. "We both had this joyful moment really early in development where we had sketched out in our terrible pen on paper doodles a story, and we brought Eric Asmussen over, a developer from another company, just to ask him 'hey, look at what we're doing. What do you think this story is?' He stood there and walked his fingers through these papers and told a completely different story than what we tried to write. And that was so exciting because he was enjoying it. He was having fun and making up stuff. And it was new and it was great. It wasn't what we tried to do, but we liked it."

Lambe added,"What was great about it was that it was completely wrong, and yet it was so consistent with everything we had drawn and written that how could it be wrong at all?"

That's the point. There are no wrong answers, no loss conditions. But just because you can't get a game over doesn't make it easy. The pen, as they say, is mightier than the sword. And like most heavy weapons in games, the higher the strength, the harder it is to wield. So I ask you this: Are you a bad enough dude to write about the end of the world?