How Max made his way to Xbox One

Meet Press Play, the Microsoft developer you forgot existed.

When Press Play got its 2.5D physics-based puzzle platformer Max: The Curse of Brotherhood up and running on an Xbox One dev kit for the first time, the Danish developer was jubilant.

In early September 2013 the Microsoft-owned, Copenhagen-based studio sent one of its specialist programmers to the headquarters of Unity, the maker of the game engine of the same name, to wave his magic wand. Work on the Xbox One port of the already-finished Xbox 360 version had just begun, but Press Play had yet to see Max moving on Microsoft's next-gen console.

Then, three days later, a screenshot was sent to the studio. It was mostly pink, but there was Max, and a beast, in the picture.

"We were screaming in the office," art director Lasse Outzen tells Eurogamer four months later. It's a cold but bright day in early December, and Brighton is glorious in the winter sunshine. A typical scene for this time of year, but the day takes on extra significance for Press Play. Producer Forest Swartout Large asks for the office wireless internet password. She wants to check her phone because today Press Play sent Max to Microsoft for certification. I can tell, the pair are buzzing.

They're buzzing now like they were buzzing four months ago, when Max, Unity and Xbox One finally learnt to talk to each other. "It was like, wow!" Outzen says, clapping. "It's running... somehow! It looked like I don't know what, and it had projections of lines going all over the place, but it was quite a moment."

If Max: The Curse of Brotherhood passes Microsoft's internal quality tests, it should launch early 2014 on Xbox One - ahead of the Xbox 360 version, despite that version being finished earlier this year. Its release will also be "quite a moment" for the little studio that found itself on the brink before Microsoft swooped in to extend its warm, comforting corporate embrace: it will have developed and shipped the first Unity-made game to release on Xbox One.

Max and the Magic Marker launched in 2010 for WiiWare, Nintendo's digital platform. "Blame LittleBigPlanet," Ellie wrote in her 7/10 review.

"We were just a small indie developer back then," Outzen remembers. "We funded the game ourselves, put it out there and did a lot of hard work to get some attention to it. It was really well received but we didn't make a fortune on it. So we still had to struggle afterwards."

Soon after the WiiWare launch Microsoft called to ask for a touch version for the old Windows Phone. Press Play obliged, taking half a year to port its platformer across. It was a common occurrence: Max and the Magic Marker ended up launching on pretty much every platform around - except Xbox.

Then, three years ago, production on the follow up, what would become Max: The Curse of Brotherhood, began, but it wasn't until the middle of 2012 that Microsoft called yet again. This time, though, things were different. The team was well into development, but the game had not released. The levels were made, and they had names, and you could play through its entirety, but it was far from finished.

"At that point everything was up in the air. It was like, ahhhhhh! And then, all of a sudden, peace," Outzen says.

Press Play was at a crossroads. With money tight it needed a publisher to ensure Max would see the light of day. Eventually, after discussions that fell through with other parties, Microsoft stepped in. But it didn't just sign the game - it bought the studio.

"There was so much value in what we had that we would never have just thrown it out and started cleaning for a living," Outzen insists, stopping short of saying Max was in danger of falling by the wayside.

"But we were really trying to find somebody to put it out there. We didn't want to give up our complete freedom to do what we wanted. That's been crucial for us all the way. So even though we were offered some things that could have saved us, we wanted to do this game the way we wanted it to be. That's the price. We were looking for a publisher and it just turned into an acquisition."

Outzen describes it as a "light touch" acquisition. Microsoft owns the company, but it lets it get on with doing its thing without sticking its nose in the inner workings of development. "We do all the games ourselves," he says. "We come up with the ideas. We do the whole production and we put it out. They want us to remain in the same kind of creative bubble." It's a similar deal to the one that saw Microsoft buy The Maw and 'Splosion Man developer Twisted Pixel in 2011. "Same story more or less," says Outzen. "Independent spirit and crazy games."

"We come up with the ideas. We do the whole production and we put it out. They want us to remain in the same kind of creative bubble."

Being first party opens doors that would otherwise be welded shut. Press Play didn't know it at the time, but when Microsoft Studios bought the studio in the middle of 2012, it wouldn't be long before an Xbox One dev kit would turn up - nearly a year before the console's November 2013 launch.

Security, as you'd expect, was tight. Super tight. It had to be, in this age of internet leaks and camera phones. Press Play had to clear out a room in its office to place carefully inside its dev kit - and secure it under lock and key.

"We got these really weirdly painted objects that were apparently the new Xbox," Outzen recalls. "They looked really odd. We couldn't do anything with them of course because we didn't have anything that could go into it. Well, we could turn it on. At that point Unity didn't support it in any way, so we had no way of putting anything on it. So it was just standing there. It was huge and it made a lot of noise! And it got real hot.

"Back then we had two programmers in a closed room with a key, and they were the only ones allowed in. They were just sat there trying to find out how we could get our Unity productions to run on the Xbox One."

Was Outzen allowed in, I wonder?

"I was allowed in!" he laughs.

Early versions of the Xbox One made a noise Outzen describes as "Foooooooooooo!" The console - at that stage little more than a PC with innards that reflected the target hardware - was so loud that Press Play's sound designer had to drill a hole in his office wall and run a cable through it into the Xbox One dev kit that was set outside.

As Microsoft made each new version, Press Play would be sent updated dev kits - another perk of being a part of Microsoft Studios. Then, in August this year, the version of Xbox One that would release at retail, the version some of you have sitting under your telly, arrived, and work on the port began proper.

"We were offered the opportunity to say whether we wanted to be on the Xbox One or not, or whether we should just go out with the Xbox 360 version, which was long into development at that point," Outzen says.

"We got the choice and we said yes. That prolonged the whole launch.

"To get the opportunity to do that instead of just attaching Max to the end of a console's lifecycle... we couldn't say no to that."

Obviously, the Xbox One version features improved graphics. Outzen mentions a "whole new" volumetric fog system, as well as other technical bells and whistles that make the most of the console's beefier horsepower. But he stresses the gameplay will be the same across Xbox One and Xbox 360.

"Of course the graphics won't be running at the same resolution, but the core gameplay will remain the same. So you get the same experience whether you buy the Xbox One or the 360 version."

This, Outzen says, was crucial. Despite the media's obsession with the new, millions of Xbox 360 owners will continue to buy games for their console for years to come. Yes, Max will launch on Xbox One first, but Press Play has high hopes for the Xbox 360 version - its first baby, the game the studio has spent the bulk of the past three years working on.

"We went to trade shows before and after we had announced the Xbox One version, and there was a huge difference in attention. I went to E3 with just the Xbox 360 version and people were like, 'oh, is this Xbox One?' 'No.' 'Ah.' That's journalists, and they're of course shopping for the new news. But there will be millions of people with Xbox 360s who will want to play and buy games for years to come, just like the PlayStation 2 is still alive."

Gameplay revolves around using Max's magic marker to create and destroy vines, water streams and platforms.

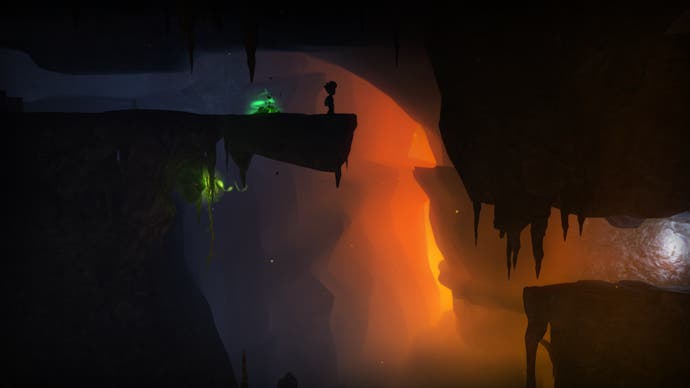

Now, the Xbox One version of Max: The Curse of Brotherhood is complete - bar any problems with Microsoft certification of course. It's a lovely-looking game, with tighter controls than LittleBigPlanet and some eye-catching puzzles. It's darker in tone than its predecessor - a better fit for the Xbox audience, perhaps - and at times tricky, with some complex sections that require lightning reflexes and speed of thought. Poor Max often bites the dust - although check points are frequent, so you shouldn't feel the frustration of having to replay large chunks of the game.

Still, when poor Max dies, you feel it. If a monster doesn't gobble him up a gaping chasm will, or a lava pit, or something else nasty. There's no blood or anything you'd consider to be gore, but we're on the bleeding edge of cartoon violence here, and I wince more than once during my quick test of a handful of stages.

Outzen says this new Max game was influenced by games the development team played in the 1990s, a time when age ratings mattered little. "We looked at the deaths of the first Crash Bandicoot game," he says. "It's insane how that character gets killed! But also Heart of Darkness, where the little boy gets killed so many times.

"We wanted to create a game where you really felt the hero was in danger. In Max and the Magic Marker he got erased every time he died, so it wasn't really a death. This time Max gets crunched and squashed and burned and everything you can think of."

Outzen also name-checks Éric Chahi's influential Another World in describing Max: The Curse of Brotherhood. "The first level in the game is called Another Land to send some respect to that old title," he says. The studio is good friends with Playdead, developer of the wonderful Limbo. Playdead used to live above Press Play's office on the fourth floor of Pilestræde 45 in Copenhagen, but the two still talk. "We used to have Christmas lunch with them, so of course we've been talking with them about how we do things." Indeed Swartout previously worked at Playdead. Underneath is Full Control, developer of the turn-based Space Hulk game. Interesting games are being made all around.

"It's very much a physics-based game, and there are so many things you have to take into account when creating a game like that, and so many things that can go horribly wrong!"

And then, Outzen brings us back to LittleBigPlanet, which Max and the Magic Marker was often compared to. "We've been looking at completely different titles just for the platforming part," he says. "We played LittleBigPlanet and other physics-based games. It's very much a physics-based game, and there are so many things you have to take into account when creating a game like that, and so many things that can go horribly wrong!"

For now, though, Press Play has been doing a lot right. It's enjoying the security of being a part of the behemoth that is Microsoft - and all the resources that come with that - and it's staffed up to 27 to make Max a reality. The future is bright, with two brand new games in full production and another few in the concept stage. Yes, Press Play is owned by Microsoft, but it seems to be in charge of its own destiny. It even released a mobile game, called Tentacles: enter the Dolphin, on the App Store as well as for Windows Phone - while it was owned by Microsoft.

"Microsoft has a whole iOS department," Outzen says, smirking. "It's Microsoft platforms best and first, but not exclusively."

Well, you probably won't be making Max any time soon for PlayStation 4.

"Probably not! Play what station?"