Is 2014 the year of virtual reality?

Come in Luigi, your time is up - why Oculus Rift is the true next-gen experience.

When Sony and Microsoft released their new consoles, mere weeks apart and with only a few months until Christmas, it's clear what they were trying to do. We had to pick sides. Again. We were being presented with what appeared to be a two-horse race, and asked to place hundreds of pounds on the outcome. I'd put aside the money, but I baulked when it came time to put it on the table.

There was no denying that both the Xbox One and PlayStation 4 were powerful and slick pieces of technology. I had no doubt they'd play host to some absolutely phenomenal games. Eventually. But I'd been here before, the start of a so-called new generation, and while the allure of the new toys is hard to resist, the cold reality is that this allure rarely pays off until months - even years - later, once developers have found their way around new operating systems and hardware architecture, and no longer have to split their attentions between the vast lucrative audience of older consoles and the smaller but more exciting wave of newcomers.

So while I felt the pull of the new, I wasn't quite ready to jump in, sight unseen. I knew the great games would be a while coming, but my hesitation was mostly down to the fact that my imagination had already been fired up by something else: Oculus Rift.

I'd encountered Oculus Rift only twice. Once in the offices of a local indie developer, and then again at a student showcase. A far cry from the glitz and baubles that a new console demands when it gets unveiled on a giant stage, but somehow the Oculus Rift was even more exciting for the humble surroundings where I found it.

Oculus Rift is a practical bit of kit. It demands that the developer does something new with it. As impressive as the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One are, they ultimately represent escalation rather than true innovation. More polygons, more speed, more, more, more. But the features that are genuinely new are on the periphery of the games - the social features, the multi-tasking dashboard, the video sharing.

The next generation consoles are powerful, and painstakingly designed to allow developers to do what they do with the minimum of impediment. The result, so far and for the foreseeable future, is an array of games that look great but are overwhelmingly familiar. They represent another mile down a road we're already travelling. There's undoubtedly appeal in that, but it's a mistake to consider that predictable forward momentum the only measure of progress.

By comparison, Oculus is, in its current form, a clunky beast. The display is low resolution, it requires a fair bit of fiddling to get the best effect and it struggles to cope with fast movements. Yet it still blew me away. The first time I slipped on that headset, opened my eyes and discovered I was inside a game, I paused. I instinctively stopped and just looked around. It was an organic "wow" moment. Even the simplest digital space becomes fascinating when you're 'there', which has a refreshing effect on the core basics of gaming. Moving, exploring, looking - we take these things for granted, and power past them to get that first headshot, that first collectible, that first achievement. Virtual reality reminds you of their power.

It's like an out-of-body experience. What would previously have been a simple 3D environment navigated on a 2D monitor becomes an actual place, and while your nerve endings are telling you that you're sat in a chair with a controller in your hands, your eyes are protesting - "No, that's clearly incorrect. You really are in a Tuscan villa. You're deep underwater. You're in a sinister forest."

Oculus introduces limitations. Despite being the ultimate FPS tool, it currently doesn't work great with shooters - the movement is too fast, the rotation too jarring. So developers - mostly from the indie and homebrew scene - are forced to look at what does work, what experiences are the most compelling, and find new gameplay possibilities there. Games become slower, not faster. Environments must rely on design to excite the sense, not just more detail. It's backwards thinking compared to the traditional thrust of hardware development, but it's liberating.

Indie adventure Asunder Earthbound takes the linear narrative openings of games like BioShock and Half-Life and evolves them into a compelling form of digital theatre. As an escaped convict on a small passenger plane in the 1930s, you must first keep your identity secret and then endure a terrifying Twilight Zone-inspired nightmare. You can play it on a normal monitor, but it's only in VR that it really works. There, your real-world seat feels like the plane seat. You look to your right and a fellow passenger talks to you. You can nod or shake your head in response to his questions. Look to your left and you see the wing of the plane, visible through the cloud and illuminated by lightning. When things get weird, you're immersed in the space, you've physically become the character. With just a few head movements, the result is more convincing than any motion-controlled game.

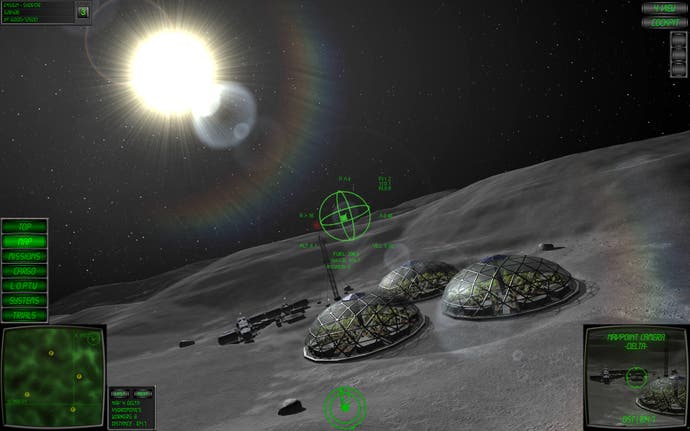

There's Lunar Flight, a mixture of flight simulator and classic physics game, in which you must guide a landing module across the surface of the moon from your VR cockpit view. It's hard to control, but the sensation of movement, of peril, as you awkwardly hop and glide over the craters, is powerful. It even offers competitive multiplayer. There's Chicken Walk, in which you play as a chicken, pecking up food with a downwards nod, returning to your hen house to lay an egg, and then keeping your chicks safe from prowling foxes. Much as you can see the blurred shape of your own nose from the corner of your eye, so in Chicken Walk you can see your own beak as you strut about. It's silly, but also brilliant.

The best games transport us to compelling spaces already, of course, but the sensory double-take that VR provides cements the experience. You feel things more deeply. You pay more attention to your surroundings, because they actually surround you. Maybe that's why so many of the early demos are horror themed, taking inspiration from Slender and Amnesia. The sense that there's something behind you takes on a physical dimension when "behind you" is a tangible thing.

And the games that are available for Oculus Rift right now are simple, often no more than demos, doodles and half-formed ideas. Valve has enabled Oculus support in Half-Life 2 and Team Fortress 2, and more established games are offering the option all the time, but those games weren't built for VR. The bulk of Rift content is coming instead from the grass roots PC development community, and it shows. There's an anything-goes ethos to the sharing page on the Oculus site, and the related game jams. People upload sketches, tentative first builds, and we then get to watch them evolve. Sometimes they fall apart in the process, but others become something fresh and exciting. This is software you tinker with, rather than diving in for ten-hour sessions, but I've found more entertainment, more potential, while rummaging through these uploads than in any next-gen console game I've played so far.

There's a lot to do before Oculus Rift is truly ready to take over the world, however. A 1080p HD display is already on the cards, and smoother head-tracking will hopefully minimise or eradicate the queasiness that some users experience. It's also often a solitary experience, but the potential for connected virtual worlds is immense. And while the kit is surprisingly easy to set up, it is a tangle of USB and HDMI cables at the moment. A wireless version is probably essential before the mainstream audience will jump aboard.

But jump aboard they will, and sooner rather than later, I suspect. Unlike motion gaming, which was propelled into the public consciousness by Nintendo, Oculus Rift is starting from a far geekier ghetto, but the impact of the experience is enough that once the rougher technical edges have been smoothed over, it has the potential to capture the popular imagination just as surely as the Wii did. If they can come up with a headset that is compatible with the SteamBox, the path to the living room is wide open.

The big difference, of course, is that having been nurtured by the PC indie scene, the creative engine of the games industry, rather than the walled gardens of commercial console development, the downward spiral of shovelware will hopefully be easier to resist when VR goes mainstream. I certainly wouldn't be surprised if Sony and Microsoft aren't experimenting with VR headsets of their own, conscious that with sales figures starting to dip for the big AAA franchises, and diminishing enthusiasm for motion-controlled games, their latest consoles will need something fresh to attract new customers as we hurtle towards 2020.

When I took my new hardware savings and used them to buy the Oculus Rift dev kit, I wasn't really doing anything massively different than if I'd bought a PS4 or Xbox One. It was a down payment on the future - on the promise of a new toy today that will play host to even greater entertainment as the technology matures. The key difference, for me, was that I have no idea what form that future will take for virtual reality, whereas I have a pretty good idea of what the big console games of 2017 will be. Uncertainty. Experimentation. Surprise. That, for me, is what a truly next-generation experience should be about.