The making of RoboCop

Thank you for your co-operation.

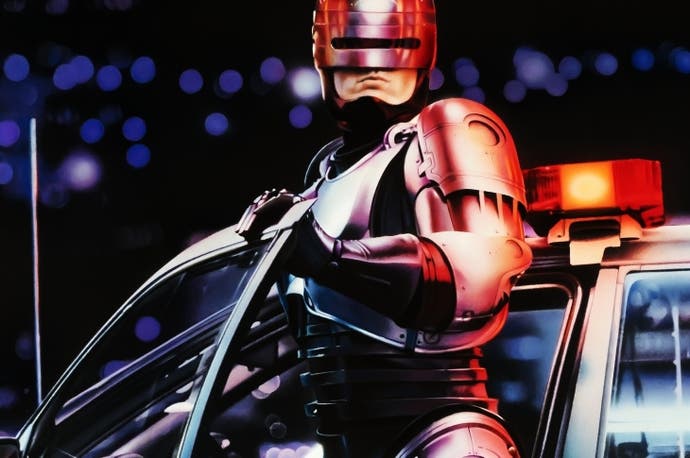

Next month will see the US theatrical release of the remake of RoboCop. The original film had an estimated budget of $13 million dollars that went on to gross some $53 million in the US alone. If one movie from the 80s defined the term 'sleeper hit', it was Paul Verhoeven's strange and violent film.

Dutchman Verhoeven had graduated from a series of critically acclaimed works in his home country to a controversial and not particularly well-received Hollywood debut Flesh & Blood - and so not much was expected of this grim and gory sci-fi parable on the perils of big business and cynical satire of American culture. Yet far away from Tinseltown and Detroit, one man in Manchester saw potential not just for a blockbuster film, but also for a rip-roaring game.

"The decision to license the game was based purely on reading Ed Neumeier's script," beams Ocean's then-software manager, Gary Bracey, who oversaw the production of many of their famous movie and TV adaptations. "It just seemed to resonate with me - the combination of action and the genre made it very compelling."

Given the relative lack of Hollywood star power behind the project the license remained, it was most definitely a risk. "That's very true," nods Bracey. "It could have turned out to be a real B-Movie. So in that regard it was a huge leap of faith." Bracey was later vindicated when he finally saw the film, though. "I loved it when I first saw it and repeated viewings have not diminished my enthusiasm for RoboCop. I think it's a fantastic movie."

But that was before production on the game had begun, and once the licence was secured for a meagre $20,000 Ocean were sent production stills, and eventually, VHS tapes containing short scenes to help them represent the movie's protagonists as accurately as possible. Ironically, given their penchant for arcade conversions, Ocean then licensed the rights of an arcade version to Data East, with whom they enjoyed a close relationship, before, in an admirably inventive move, using Data East's arcade game as a reference for their home versions. As was common at the time, shoehorning an intense cinematic experience into a 48k ZX Spectrum or Commodore 64 computer would be a formidable task; fortunately the Manchester-based company were already highly experienced in the conversion process, although RoboCop was about to arthritically stomp on all of their previous efforts.

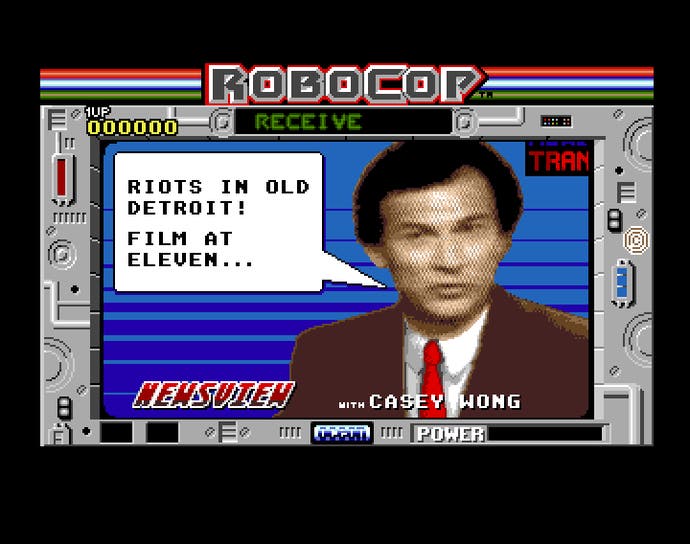

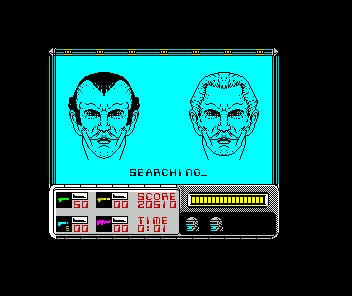

"Even though we were basing it on the arcade game, we wanted our home versions to differentiate from the coin-op; so we came up with the idea of incorporating some extra sections to make them a little more unique," explains Bracey, referring to the photo-fit and hostage scenes that occasionally puncture the run-and-gun action template laid down by Data East's arcade machine. Ocean was determined that even if the movie bombed at the box office, its game would be able to stand on its own merits. When, as Bracey calls it, the 'perfect storm of great game plus great movie' was formed, everyone at the software house knew they had a sure-fire smash hit game on their hands. Yet the development of RoboCop was as frantic and frenzied as many other big games of the era. Constantly under pressure, the respective Spectrum and Commodore teams worked around the clock, battling not only time, but the restrictive nature of the hardware. Each computer had its own drawbacks, although Ocean had already assembled an experienced team to combat and work around such issues. Coding duties on the Sinclair machine were handled by Mike Lamb, veteran of titles such as the acclaimed arcade conversion Renegade and another game-of-the-movie, Top Gun.

"We were really short of memory," grimaces Lamb, "so I had to do things such as make random masks for the dying baddies. They basically dematerialised like they're being beamed up in Star Trek because we didn't have room for any further animation." Despite more hardware support and memory, things did not prove much easier on the Commodore 64. "The eight sprites on a line restriction was always a pain with games like RoboCop," bemoans C64 lead coder John Meegan, "as even with multiplexing, you had to be careful as the sprites would tear or glitch if the reused sprite crossed itself. And the colour scrolling was a huge processor hog, as was sorting the sprite table."

One obvious potential issue that didn't transpire, however, was the level of the film's violence, which was apparent even from the script. "There was never much discussion on that," says Meegan, "as in those days violence in games was very abstract." Lamb, whose team worked separately from Meegan and his colleagues, recalls: "I think we might have wondered about replicating the scene where the guy gets shot in the groin by RoboCop; now I think about it, if we could have made the game more violent, we probably would have!" he adds. "That was never going to happen," counters Bracey. "We perceived RoboCop as a game for everyone, even if the younger audience were unable to actually view the R-rated movie!"

Ultimately, both the Spectrum and Commodore teams created outstanding and playable adaptations of the dystopian movie, despite several key differences in the game design. On the ZX Spectrum, RoboCop would infamously "freeze" whenever he was hit, leading to some frustrating moments if the player wasn't careful, while the Commodore 64 saw the silver cyborg blessed with just one life - although he did have the rather ungainly and unlikely ability to jump. Despite this, both versions were criticised for their steep difficulty curve.

"RoboCop was way too tough," says C64 coder John Meegan, "essentially because when you'd programmed and debugged the same gameplay over and over again, you knew exactly what to do and when, while the poor gamer doesn't." But Mike Lamb disagrees, adding: "The initial play testing said the game was too easy. So we made it harder, and I think got it just about right. Once you work out the patterns of the enemies, it's actually fairly straightforward."

Now convinced they had a hit on their hands, Ocean lavished a huge glossy box on RoboCop and enforced a heavy advertising campaign. "They were expecting Operation Wolf [a high-profile arcade conversion] to be their number one at Christmas," says Lamb proudly, "so we were dead chuffed when RoboCop got there instead." For many of those involved, RoboCop represented a then-highlight of their careers and a platform for further success. "It was the biggest game I'd been involved with and I had enormous pride in what the developers achieved," notes Bracey, "and it was also the first license I had actually identified myself so it felt great!"

That 'perfect storm' continued to benefit Ocean as the time pressure placed on the developers paid huge dividends. RoboCop the game was released in time for Christmas 1988, just as the UK VHS video release was flying off the shelves at both rental and retail stores, and became a huge hit. Work had already begun on an Atari ST version as Ocean looked to exploit the expanding 16-bit computer market, and soon the game was also ported to the Commodore Amiga and Nintendo Entertainment System, the latter by Data East; it was the movie license that just kept on giving. Bracey himself even found fame (sort of) as parts of his face were used for the 16-bit version of the photo fit mini-game.

But the overall legacy of Ocean's RoboCop sets it apart from most other titles of the era. It was reportedly the first million-selling videogame, and also the first to be licensed back to an arcade company by a home computer software house. But perhaps most importantly, it helped its publisher weather the storm of the late 80s, when the power base of videogames slowly began to shift from home computers to dedicated consoles such as the NES and Master System, and then their successors, the SNES and Mega Drive. It spawned two sequels (including an ambitious first-person shooter, RoboCop 3, on the 16-bit computers and PC) and launched a succession of careers for those behind its creation.

Not bad for an unholy monster.