Down the replay rabbit hole

Why Ken Levine's plan for endlessly replayable narrative could be a risk not worth taking.

Ken Levine wants to chase a dragon, and whatever the (inevitably more complicated) truth behind the shuttering of Irrational in order to do it turns out to be, let's take that recently restated goal at face value. "To make narrative-driven games for the core gamer that are highly replayable." Huge challenge. Noble sounding goal. Bad idea, looking as seductive on paper as a treasure map promising great riches and fortune, but ultimately leading right down the same kind of rabbit hole that Balance of Power creator Chris Crawford has now been spelunking for over 30 years.

The core of the problem is really in his own comment, "I spend five years working on a game and 12 hours later the player is done with it, and that is heartbreaking." It's understandable. More than understandable, it really sucks. I'll spend less time writing this article than he slaved away scripting dialogue for a single scene of BioShock Infinite, with the possible exception of the one where Elizabeth completely arses up the point of Les Miserables, and it'll still be depressing to see it vanish from the front page by Tuesday. And that's BioShock Infinite, which got no shortage of ink and talk. Most games disappear far faster, and are lucky to make so much as a ripple to mark the sweat that went into them.

However, the hopes of a writer aren't necessarily the demand of a reader, viewer or gamer. Before trying to 'fix' anything, we need to be clear on what the problem actually is, and Levine's isn't that most players are draining narrative games dry with only a quick pause for dinner. Near the end of 2012 for instance, BioWare revealed completion stats for all its recent games, and Mass Effect 2 came top... with 56 per cent. Dragon Age: Origins? 36 per cent. Now, in fairness, those are long, complex, hardcore games. The numbers don't seem to change much for others though, as a look at Steam's Global Achievements will attest. These aren't perfect numbers, admittedly, with factors like offline mode and people who own the game but never actually play it meaning that not even a 'Loaded The Game' achievement would get the full 100 per cent.

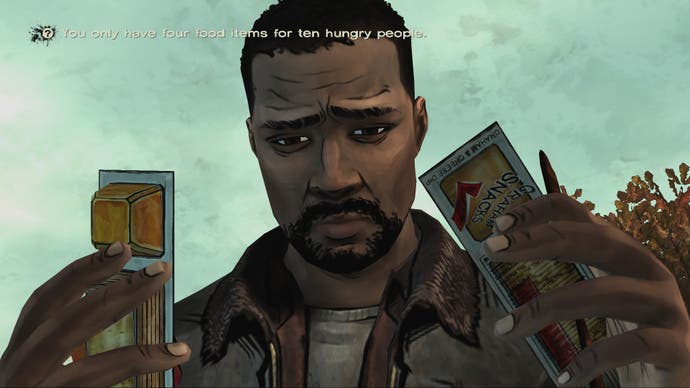

Still, it seems notable only 46.5 per cent of players are down as finishing Portal on PC. Yes, that Portal. The three-hour long, arguably most beloved game of its year Portal, which spawned more memes than a pregnant spider reincarnated from the lyrics of Never Going To Give You Up. More recently, how about The Walking Dead? Starting with 81.8 per cent of players who picked up its first achievement, only 65.8 per cent stuck around to finish even Episode 1. By the finale, ignoring the DLC, only 38.5 per cent of players are demonstrably hanging around, never mind heading back to see what happens if the usually affable Lee is a complete arse instead.

When even bite-sized, much-acclaimed narrative games are struggling to keep people entertained, worrying about replay seems an odd goal. In a way, it seems to be missing a few basic facts, not least that fans will happily return to old games like they would a favourite book or film - something like Grim Fandango, or most of GOG.com's catalogue inspires return visits without necessarily changing a single line of the story. Another is that while games like Deus Ex, Alpha Protocol, Dishonored and other games whose systems are in service to narrative happily use replayability as a sales pitch, their real benefit is actually responsiveness - in being able to say, "I want to take this on as a stealth gamer," or feeling that the game paid attention to how a particular mission played out rather than simply being a bit of forgotten action sandwiched between cut-scenes.

But let's put this elephant in the room into the corner, at least for the moment. Can systems do a better job of storytelling than crafted content? Historically, no, and while we certainly shouldn't use that as evidence that there's no point trying, it's hard to see how any technology short of a magic futuristic AI will be able to beat the problems they demonstrate. The first of those is that any story, any setting, any characters, and any mechanic gets old fast, as indeed seen by Levine's own BioShock. The first presented us with one of gaming's most imaginative, best realised locations, only to have fans yawn at the idea of returning to it for BioShock 2.

There are certainly systemic games that can keep people's interest in the long run, but at most they sprinkle bits of lore and a premise into their worlds and focus on being a stage for stories rather than actually trying to tell one. When they try, we get MadLibs, with the resulting stories passing muster because either everyone is meant to be impressed by too the technological achievement to spot the lack of fun - Skyrim's Radiant AI for instance, or the older AI-driven adventure Sentient - or the effect is entirely reliant on the atmosphere. Spy games Sid Meier's Covert Action and Floor 13 spring to mind as short-lived successes. Once the 'I am a ruthless secret agent' vibe fades though, everything is quickly laid bare. As humans or human-like infiltrators from the planet Zorgoth as the case may be, we're fantastically good at spotting patterns and figuring ways to use and abuse them, even at the cost of our own fun.

It's obviously too early to know exactly what Levine has in mind, and in talking about it, even he's admitted that he's dealing with early ideas - the closest to a direct example being a kind of narrative Lego, where characters can be broken down into pieces and played with in various ways. Elizabeth in BioShock Infinite for instance can respond to many of the things that she walks past, but always in a scripted way - the only real difference between plays is whether or not she actually makes the comment she's programmed to be able to. In a hypothetical future game, she'd be able to react on the fly; presumably in terms of things like relationships and decisions rather than just random responses.

To see how the problems emerge though, let's try a practical example - again, not specifically what Levine is working on, but something that at first glance seems to be perfect for this kind of concept - a murder mystery, where the details are different each time. As an intellectual exercise, that offers plenty of meat and in theory at least, ideal ground. We can have shifting relationships, and investigating systems where clues are scattered around to be discovered, and a cool interrogation system where character secrets can be uncovered and notes made... and that all sounds like a perfect mystery game until you take a step back and realise that it's essentially a glorified Cluedo rather than Christie, likely with bolted on mechanics of the kind LA Noire couldn't keep interesting over a single, crafted game. There are reasons that police procedurals actively keep procedure in the background. Procedure soon gets dull. So do most procedural games that can't offer a constant flow of risk and reward that it's hard enough to get without pretending that the story being told by the mechanics actually matters.

To take the most basic, there are reasons people say a good story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. It's hard to dangle that sense of closure as a carrot, or provide a reason to keep going for it after it's been all crunched up. Even great procedural games like Spelunky or The Binding of Isaac or FTL typically feel 'done' once the ending arrives, unfinished business or not. Closure is important. It's not simply what ends the story, it's what provides a sense of release; a good one elevating the whole experience to the stars, a bad one killing it dead.

Further, to make even this basic concept work as a replayable game, we have to make a lot of sacrifices. First, it has to be short. We've seen that even getting half a game's players to finish a game once is an achievement, and it gets harder the longer the game becomes. By focusing on replay though, and repeated iterations of loops and mechanics and procedural generation it's not going to be long before the systems are exposed - directly, with problems like repeated text (or worse, repeated jokes - the lingering torture-death of comedy) and indirectly, as any passion in the characters is replaced with the rattle of dice and obtuseness of chance.

Not for nothing does stealth AI have to work like robots and keep a running monologue of its thought process - in interactive fiction, appearance is everything. Information presented feels inherently simplistic, like summing up a whole relationship with a number. Information withheld is useless, leading to character actions feeling random or paths untaken simply being invisible. When characters feel like systems though, players treat them primarily as systems - as puzzles to be solved and cracked, not as fellow actors in the play. It says a lot that for all the karma systems and relationship models that have been tried, not to mention branching that's gone from basic good/evil paths to the downright fractal Alpha Protocol, the single most effective character relationship trick ever pulled in an adventure game was the simple message "Clementine will remember that."

Could this be mitigated by additional scripting to give them proper personalities and backgrounds and make them characters in their own right? Sure, absolutely. But at that point, you may as well just break out a copy of Final Draft and write a story the old fashioned way - both for the workload involved, the ability to polish the story being told, and to feel a sense of creative ownership over the result rather than in the technical algorithms behind it.

Obviously, this is not trying to predict exactly what Levine has in mind for his games, which could be anything, in any genre, if he even has a big idea at all yet. It's simply an example of how big the challenge is, even in the kind of story whose components would seem to benefit from it. Can it be fixed? Sure, no problem. I point you to an erotic thriller called Masq, which was the internet's narrative darling a few years ago, and proudly declared branching to be its solution. Even it though could ultimately only claim an average of five plays per player, and that's on a page specifically intended to answer criticism that nobody would want to keep heading back in.

In gaming, as with anything, it's never a good idea to say that something is flat-out impossible, and yes, I've already ordered a hat to eat in the event that Levine pulls this off and reinvents the whole nature of in-game storytelling. (Just to be safe, it's a chocolate one.) What he's talking about though isn't simply a technical challenge, but one that goes right to the core of how games are played and stories are told without really offering benefits on the story side or appreciating that a 12-hour game is only over after 12 hours if it had nothing to justify it living on beyond that. A great poem doesn't need to be a novel to reach its full potential. Nobody ever said Hamlet should be a Choose Your Own Adventure, or to be more accurate, nobody who should be allowed to cut up their own food. There's always one.

Really, if anything, BioShock Infinite needed the tender caress of an editor, and a gaming world willing to accept AAA games just being the length they need to be to tell their story without padding. After all, Peter Jackson only needed nine hours to tell the whole Lord of the Rings. How many game narratives can honestly say they even get out of the Shire in that amount of time? As interesting a challenge as replayability and procedural stories are, there are bigger problems to deal with right now. First, let's master telling game stories worth both playing and replaying. Then, we can worry about teaching computers to do it for us.