Finding someone to thank for the good stuff

We all know the key people that gave us Ghostbusters, but who's responsible for our favourite moments in games?

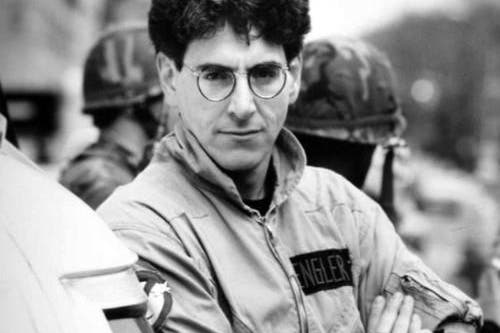

Goodbye, Harold Ramis - and thanks for everything. Thank you so much.

Inevitably, I've been thinking about Ramis quite a lot since this Monday, and I've realised that what I really feel, along with the surprise and the sadness, is gratitude. Thanks for Ghostbusters and Egon Spengler. Thanks for making being a nerd with glasses in the early 1980s a little easier. Thanks for Groundhog Day and the joys of the Pennsylvania Polka. Thanks for suggesting that magic might lie behind the most overcast of skies, the most tedious of weatherman assignments. Thanks for making the case that happiness is inevitable.

Other people were involved with all of this, of course - auteur theory rarely makes much sense since most films are, ultimately, group efforts - but it's often relatively easy with movies, and with music, and with painting and literature and all the rest, to see where to direct a lot of your appreciation. Ramis co-wrote Ghostbusters, and that's always given his low-key performance as Egon, the quintessential straight man, a kind of gleeful subversiveness. Equally, according to this wonderful piece in the Guardian, although he came to Groundhog Day once a script had already been written by Danny Rubin, he then stripped it of its distracting non-linearity. He saved the movie from voguishness and made it - somewhat appropriately - timeless instead.

Two classic films in which his impact is clear, then - and that's just in my personal top 10. That's before you take into account the likes of Stripes, of Meatballs, of Animal House and even Analyze This. What a career - and, I suspect, what a man to have done it all with such obvious warmth and modesty. It's made me think about things - about the great films of the 1980s, about being a kid and watching Ghostbusters on tape for the 100th time until I even knew the order of the adverts, and about gratitude in general. It's made me think about how you wish you could thank the people who have done so much for you - thank them for all the things they've done without really knowing it.

And it's made me think how particularly hard this is with games. Forget auteur theory - although we now have plenty of auteurs, for better or worse. Video games too often suffer a sort of anonymity theory instead. Many of them are massive productions where dozens of fiercely specialised heroes toil thanklessly behind the most baffling of job titles. Story and performance are, far more often than not, mere trappings here rather than the beating heart of the appeal. The things that really get to you are mechanics - mechanics enhanced by the perfect animation, the perfect audio cue, the perfect context, the perfect position in the numbers curve. Who do you thank for that?

Granted, sometimes there's an easy answer. The indies are full of one- and two-person shows. I did the tech and the design, she did the art and the audio.

Then there are the answers that seem easy. Scanning the recent headlines, how about Ken Levine? Now there's an auteur, right down to his egg-white omelettes and his beautifully weighted interview answers. He is BioShock, and yet, which bits? He dreamed up Rapture and Columbia, presumably, and sank one beneath the waves and set the other amongst the clouds, but did he lay out the beats of Infinite's brilliant opening section, with its storm-lashed lighthouse and its pitch-perfect Close Encounters reference? Did he set your rocketship racing through the sea mist, and design its manacled passenger seat that so elegantly invokes the cold chill of the electric chair? How about the wonderful mechanical clunk of a new objective appearing? The nasty snap of the pistol shot? This was a huge undertaking - wherever you look there are unsung heroes.

In truth, if you're like me, you'll have little idea of who was responsible for many of your favourite moments in many of your favourite games - and that's a crying shame, since a lot of games are their best moments, living on in your memory, playing over and over and getting sharper and more distinct each time. To me, Arkham City is the grapnel boost. Batman has the best ropes! Look at it go, unspooling from the end of the gun with a puff of smoke, first a coiled Slinky of wire, then a taut black line connecting you to your destination. More than the voice, the cape, the Joker babbling in your ear, it's this that really sells the fantasy of the Dark Knight. Thanks, animator!

Equally, Burnout 3 is aftertouch. Before Takedown, crashing in racing games had always been a disaster, and then Criterion came along and it became a gleeful, vengeful celebration of all things arcadey. Your car becomes a homing missile as time slowed, the audio started to warp and stretch, and your thumbstick steered your flaming wreckage across the tarmac and into a rival with just the right degree of somnambulist heft to proceedings. The perfect failure state for a game about driving badly, but driving badly well. Thanks to everyone who made that possible.

While we're at it, how about the hit-pause in The Wind Waker, how about Rain of Vengeance in Diablo 3, how about the sound of feet beating against metal gantries in Impossible Mission (I know who to thank there - solo designer Dennis Caswell who is now, I'm delighted to report, a poet)? How about the Agency Tower? How about phasewalking, and how about the perfectly executed Overwatch, where the camera zooms in close and you manage to pop a Sectoid's head off its shoulders despite a 40 percent success prediction?

To love games is to be furious at the millions of things they get wrong, and to be thankful for the billions of things they get right. If only there was an easier way to direct that thanks - towards a friendly face, like Harold Ramis, toiling away with that warmth, that modesty, working hard to keep you happy.

Harold Ramis, 21st November 1944 - 24th February 2014: "We had part of a Slinky - but I straightened it."