Out There review

Lost in space.

It's the 22nd Century and, as those of us alive at the start of the 21st Century might have predicted, things aren't going so well for humankind. Earth is exhausted, grown pale and plundered by its dominant species' greed and unchecked procreation. But there's another pressing issue for Out There's protagonist, one of the astronauts sent into space to locate more resources for the folks back home: his missing CD collection.

With the knowledge that he would be put to sleep aboard the Nomad while the spacecraft crept towards Jupiter, he chose to leave his music at home. After all, he wouldn't have much need for it while lost in cryonic sleep. But when he eventually awoke, in some far-flung solar system, it proved a regretful decision. Alone out there and without a Material Girl or a YMCA to dance to, you've only the flitting of the stars and the fine whirr of the screens for company.

This is just one of the hundreds of succinct snatches of storyline that contribute to Out There's ambiance: a bleak yet hopeful quest for survival against a universe of stacked odds. These diary entries pop up at the start of each new day and add a texture of melancholy narrative to what is, beneath the theme, a cruel and unforgiving strategy game. Out There is a game of risk. You play as a lone space survivor, adrift in space with only a tankful of fuel and oxygen and a bleeping red light on the map to act as a destination. You must gamble your resources as you creep towards your goal, choosing where to stop off to replenish your stocks. The risk is that you run out of fuel or oxygen before you find a stop-off point. The reward is that you get to see another day marked by another sunrise from a new sun.

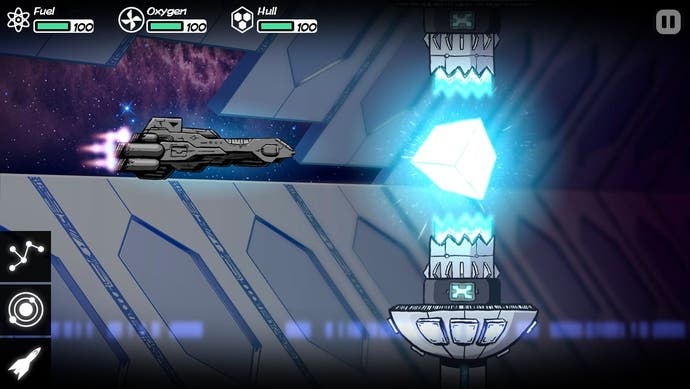

Your spacecraft is comprised of three essential and limited resources: fuel, oxygen and sturdiness, as measured by wear and tear to its hull. Each of these assets is measured on a scale of zero to a hundred. If you run out of fuel, your ship is left to drift in space and it's game over. If you run out of oxygen, you suffocate and die and it's game over. If the integrity of the ship's hull is broken, you're sucked into the infinite void and it's game over. Almost every action you perform in the game costs fuel and oxygen, but you must speculate to accumulate.

The game world is laid out as a giant star map, your ship a pulsing icon in the indifferent expanse. You are able to travel to any moon or star within its range, a journey that costs both fuel and oxygen. Once you arrive in a new orbit, you're able to land on any planets in the vicinity where you can mine for minerals (used to repair your ship's hull), drill for fuel or search for inhabitable planets where you can restock your oxygen. You might land on a planet to drill for fuel only to recoup a fraction of the amount you spent landing; or you might hit the jackpot and collect enough to keep you going for weeks. Such is the capriciousness of travel into the unknown.

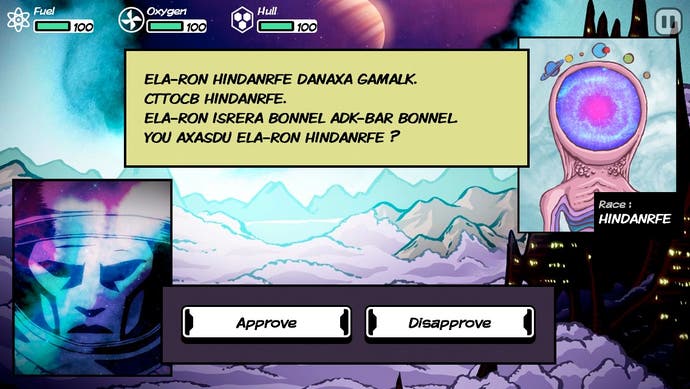

Your ship is laid out like one of Resident Evil's suitcases, with a limited number of slots in which to house equipment (everything from the basic, such as a telescope to allow you to identify neighbouring planets, to the complex, such as a terraformer used to enable uninhabitable planets to support life) and resources: fuel, oxygen and other minerals. At times, you might come across an abandoned ship floating in space and you may choose to trade up. It's usually a trade-off. Some craft have farther reach and better fuel efficiency, but with less space to store resources. Other times you might find an inhabited planet, home to an alien race with whom you can trade resources and information. Everything you do must pull towards the goal: stockpiling resources to survive while pressing deeper into space, towards one of the destinations that opens up to you as you gather arcane information.

Out There's theme is clear and persistent: space is lonely, deadly and unimaginably expansive

What lends Out There its unique potency is the speed at which it can all go wrong. Make a couple of wrong moves in sequence and you can quite easily find yourself on the verge of catastrophe. Run out of fuel before landing on a planet and you have one final pot-luck chance to make a successful touchdown. Fail on this dice roll and there are no save points to return to.

The moment you gamble too much and lose you're awarded a score, calculated from the number of star systems that you visited, the number of new technologies you discovered, the number of spaceships you found, the number of alien races you discovered and the number of planets that you terraformed to support life. Your imprint and effect on the universe is clearly outlined. The quest into the unknown is exhausting and you may well need a break. But the urge to return in order to press that much farther into its mysteries is strong.

Out There's theme is clear and persistent: space is lonely, deadly and unimaginably expansive. The odds of survival off-world are slim and there's nobody to come to your rescue. And yet Out There also reveals something of the human pioneering spirit and its twin: the urge to survive till the final lungful of oxygen is expended. And if and when you do manage to scrape through another day, it's a game that allows you to marvel at the unlikeliness of all this as well as the miracle and fragility of life.