How the developers of Endless Legend see the end in sight

Even if their Early Access peers may not.

They're making no boasts about being trendsetters but, long before Amplitude Studios put Endless Legend on Early Access, before Early Access even existed, they were already experimenting with Games2Gether, their "brand new way for players around the world to participate in the creation of a video game." Games2Gether helped Amplitude to develop their début title, the 4X strategy Endless Space, polling players to see what was popular and even letting them pitch their ideas to the team.

Games2Gether launched in May 2012, almost a year before Steam Early Access began, and may well have had some influence on its development: "It's only after the final release of the game that we had the Valve guys come over to Paris and tell us 'You know, I think you were the first people to do this,'" says creative director Romain de Waubert. "It was pretty cool."

Amplitude was pleased with the feedback Games2Gether gave them, believing it improved Endless Space considerably, so it makes sense for de Waubert to turn to Early Access for Endless Legend, a spiritual successor that replaces the former's ethereal sci-fi setting with a slightly left field take on fantasy. Still, he has some reservations.

"I think releasing a game in its alpha stage is way more stressful than releasing it as a finished game," he says. "You don't know how people will react to an unfinished product. It's so random. I see a lot of people are more wary now, because they've participated in one, or two, or three Early Access games that haven't been completed, that will never be completed, or that were very buggy."

"Releasing a game in its alpha stage is way more stressful than releasing it as a finished game."

It may be a surprising position for a man you'd think would find all this alpha stuff to be old hat by now, but Games2Gether was Amplitude's audience and the developer made sure to build close ties with this community. Entering Early Access opens Amplitude up to a much wider and far more critical audience, something that de Waubert says puts even more pressure on them to show the game at its very best, even at this early stage.

They are off to a good start. Endless Legend has the same mixture of empire building, complex economics and indirectly-controlled combat as its predecessor, and Amplitude have been reflecting on both lessons learned and the recent crowding that's happening in the fantasy 4X corner. With the arrival of the second Warlock game, with last year's Eador and with Age of Wonders 3 receiving a warm response, de Waubert thinks it's more important than ever to not only try something different, but to deftly sidestep the clichés that the genre can walk into.

"I've been looking at the 4X games that've come out in the past year and I think they all seem to be following the same formula," he says. "Where they innovate is not where I'd innovate. For me, even with the 4X games I love, there's always something I wish had been done differently, something I'm not so happy with." This doesn't just mean mechanics, he says, but theme and presentation. Some of Amplitude's team previously worked on the Might and Magic series and de Waubert is particularly keen to avoid what he calls "extremely 'classic'" fantasy.

"It's difficult, because you want to create something original, but you also want people to know where they are, you want them to have an entry point," he explains. "That's what's most important for me, to create a fantasy that you can believe in. f you go too far in the world creation and make everything completely new and unique, then people can't relate to it. But if you do something that's so classic that they've seen a hundred times, they're not going to be attracted to it."

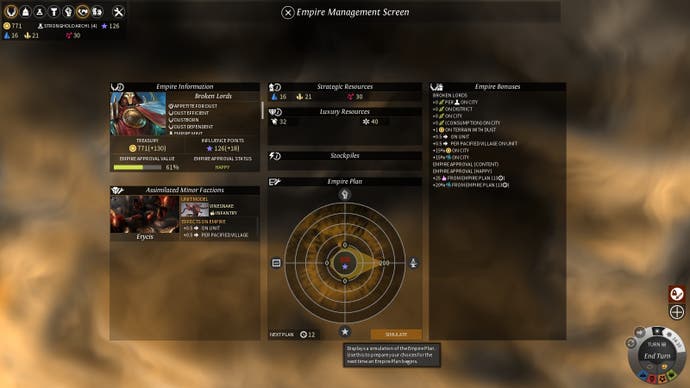

The result so far is a distinctive game populated by creations that seem strangely twisted beyond fantasy norms, from the elf-like, aggressive Wind Walkers to the Broken Knights, long-dead lords who are nothing but animated suits of armour. These factions gradually spread their way over a strangely Lilliputian world made of up tiny and sometimes disconcerting details. We have a certain television show to thank for that.

"The terrain was the first thing, that was how it all started," de Waubert says. "We knew we wanted to do it with hexagons right away. We were afraid that if we did it with squares it would be far too blocky, but if you'd seen a picture of what we were doing [at first], you would've thought it could've been Civilization, Age of Wonders, Heroes of Might and Magic. It could've been anything and we were bored looking at it. At the time we were watching a lot of Game of Thrones and were thinking 'Hey, it's interesting how they do that introduction.' So then we took inspiration from that, with this kind of toy-ish approach."

That terrain isn't just for show. Wherever armies clash, that same terrain becomes their battlefield, with no switch to any battle map. Units must contend with the same obstacles that might impede theme during a regular turn and other armies nearby are able to march into the fray. Battles can't be micromanaged, however, as de Waubert believes that the player's role is of a ruler, not a general. Units are issued orders, over three phases of two rounds each, and then react as the battle unfolds. It doesn't just give a sense of distance, it also means battles can result in a draw, with wounded armies limping away unsatisfied.

Endless Legend also has a clearer UI than Endless Space, one that doesn't require players to spend as much time hovering the mouse over statistics, and Amplitude has tended a simpler tech tree, something that will surely cheer strategy horticulturists. Endless Space's tech tree wasn't so much overgrown as it was a twisting cryptid whose murky branches obscured the clarity that science should bring.

"When I was with our testers, it was interesting to watch them looking through the science tree for the first time. So many of them were nearly dying on the spot, saying 'Dude, I don't think I want to play this game...'" de Waubert recalls. "We had tester who, on his first turn, spent one hour just looking at it. He was going over every single technology to try to understand where he should go. Another thing I didn't like was that it was a tree, that you had a set path you had to take when you wanted to go somewhere. I thought it was constrictive."

"A lot of people see Early Access as a way to make money before finishing a game. I would say we're pretty annoyed by that."

The solution is a system that divides technology into ages that act like tiers. Research enough technologies in your current age and you unlock the next. There are fewer dependencies and players are free to fill out an age or rush ahead to the future, though at a cost: "You get very interesting strategies that appear, ones where people try to race as fast as they can up the ages, but then they miss out on very early technologies," says de Waubert. "The price of the technologies increases all the time, so missing out on early tech can become very expensive later on."

And Amplitude know what strategies their players are employing because they can collect data from Early Access games, studying the metrics of how they play and adjusting elements that they think are unbalanced. What they aren't doing, de Waubert insists, is relying on players to report errors or to find bugs for them. That, he says, is not acceptable.

"For that, you have QA, or you should have QA," he says, quite unequivocally. "I understand smaller developers won't have as much access to QA, but QA is an extremely important part of development. Even the smallest developers need some QA and that should not be paying customers."

Early Access does not disavow developers of responsibility, de Waubert adds, and they should still be prepared to offer something worthwhile to their players, along with the guarantee that improvements are to come. He says he's also concerned that many use Early Access as a way to shore up development costs, to tide themselves over.

"I think a lot of people see Early Access as a way to make money before finishing a game," he explains. "I would say we're pretty annoyed by that. For us it's a way to gather feedback. I think if a developer needs the money from Early Access, their game will already be in bad shape and then they'll enter this downward spiral: They need the money, but people don't like the game because it's in a bad shape and they feel like they've been cheated. If you want to get feedback, you can't get feedback on an unplayable game. It's better just to show screenshots because all people will talk about are your bugs."

It's to Amplitude's credit that, while Endless Legend is still quite incomplete, missing most of its diplomacy and with the tech tree yet to mature, it's one of the least buggy Early Access games I've seen. Even at this stage, it's polished, it's pretty and it sports potential. There's a lot to be done, but de Waubert is optimistic about both his game and, in spite of his reservations, even about this new mode of development. He feels it removes many of the uncertainties in making a game.

"I don't know how Early Access will evolve, but I'm very happy with the way that we're using it and I really want to keep working this way," he says. "I don't want to have to go back to the classic system, what we used to do, where you release a game and you hope it does well. This way, at least you maybe know how good the game is before release."