Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor promises plenty of strategising - and accidental chaos

Well, this is orc-ward.

Gragnor - I think I've remembered the name correctly - was afraid of beasts. Specifically, he was afraid of caragor, the thuggish cat beasts who roam the scrubland of Mordor, displaying surprising litheness when it comes to climbing walls, pouncing on foes, and ripping the throats of their victims open. Gragnor was a captain in the Uruk army, one of two personal bodyguards to the warchief I was ultimately gunning for. To make that final confrontation easier, my plan was pretty simple: brainwash the bodyguards and use them to undermine the warchief himself. Once he was weakened by their betrayal, I could kill the chief, replace him with one of my own guys - hey, maybe Gragnor? - and move on to my next job.

Getting to the first bodyguard was easy. I had a decent amount of intel here, so I tracked him across the open map, clambered up a tower, dived on him from above, and won him over to my cause using my special wraith powers of persuasion, which basically involves grabbing someone, slapping a hand on their forehead, and watching as magical white energy flows into their cranium. That was surprisingly straightforward, and the only hiccup occurred when I accidentally stumbled into a group of tooled-up Uruk footsoldiers while looking for the button that allowed me to crouch. Luckily, I then found the buttons for my bow - one trigger to aim, one to draw back and then release - so sorting that lot out didn't take too long.

The second bodyguard was Gragnor - I'm sure that was his name - and I followed him to the marshes. Gragnor was cut off from his Uruk associates, and out there on the marsh he ran when he saw me coming. I decided to chase him. He was fast, so I saddled up one of those caragor that were grazing nearby. Hadn't I recently read something about them? Oh yes: Gragnor was afraid of the caragor - a spy had told me this already. Gragnor swiftly went nuts, and it turns out that he probably had good cause. When I eventually dismounted to do the forehead trick on Gragnor and get on with my ultimate mission, the caragor impulsively mauled him to death before I had time to act. Godspeed, Gragnor.

I didn't expect emergent comedy to play such a central role in Shadow of Mordor, the new Middle-earth game from Monolith Productions. Happily, though, emergent comedy seems to be your constant companion throughout this open-world adventure - at least if you play as carelessly, or as stupidly, as I do. On the surface, Shadow of Mordor looks to be pretty derivative stuff: the you-against-all-of-them battles owe an obvious debt to Rocksteady's Batman Arkham games with their counters, their rhythmic blows, and even a wraith-powered version of that dandy beatdown move the Dark Knight can pull off, while the scrabbly parkour combined with the whole business of infiltrating enemy territory and plotting the nasty deaths of your targets will put you in mind of Assassin's Creed. So much so, in fact, that a Ubisoft developer took to Twitter earlier this year to ponder the similarities.

Luckily, beyond the basic fact that a game combining Batman and Ezio was always going to be a bit of a blast, Shadow of Mordor has other ideas bubbling away too. Other influences, you might say, since Michael de Plater, Monolith's director of design, previously worked on the Total War series, and if there's one thing Total War loves, it's playful systems. (And elephants, but that's less relevant here.)

Poor old Gragnor's death was a consequence of what Monolith's referring to as the Nemesis system. It's extremely cool. Shadow of Mordor is set somewhere between The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in Middle-earth chronology, and it follows a ranger who's been killed and brought back from the dead by wraiths at the very moment that Sauron stages his return to Mordor. If these names mean very little to you, the only thing you really need to know is that the Middle-earth books are all about power when you get down to it, and the power they're concerned with generally comes with a corrupting influence. There's plenty of room for heroes in this world, but there's also plenty of leeway for heroes to behave in a rather underhand manner to get at what they want.

Hence the Nemesis system. While Shadow of Mordor features a central storyline filled with all the quests and third-person stabbing, sneaking and clambering action you might expect - and it's handled stylishly - you'll spend a lot of time in the game's army screen, where the forces you're up against are laid out in front of you like ranks of painted lead figurines. My mission in the current demo was to infiltrate an Uruk stronghold and raise my own militia, and this screen - this detailed glimpse of Uruk hierarchy - was the best place to start.

For a game based on the rigid lore of Tolkien, Shadow of Mordor has a wonderful sliver of procedural chaos at its heart. Testify: the best means of raising an army is to replace the warchiefs at the top of the Uruk heap with your own guys - and those warchiefs will be different each time you play through the game. Monolith's approaching its enemies dynamically: individual soldiers will remember your encounters with them and will also rise through the ranks depending on a number of different factors within the game. They'll level up and bear the scars of previous battles, and while this stuff generally sounds like flim-flam, you can actually see it happening as you play. When I was killed by a lowly footsoldier at one point, I saw him promoted to captain before I had been able to respawn. I knew that the next time I met him, he'd be a real pain about that.

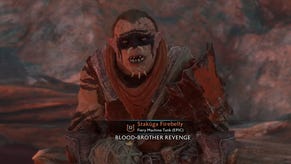

By the time I got to the army screen, all the guys in the top spots were really nasty - and they were generally pretty screwed up, too. One was an alcoholic, saddled with bottles of potentially explosive grog and incapable of gathering good bodyguards because of his drunkenness (or his flammability). Another was massively diseased and surrounded by buzzing flies. Shadow of Mordor's character models are an early next-gen glory, glistening with Uruk sweat and covered in serrated Uruk armour: these monsters are the perfect canvas on which to paint a history in scar tissue and stitches.

You'll do a lot of your plotting in the army screen, since you can zoom in on a warchief and immediately see the bodyguards who are loyal to them. As long as you have the intel, you can also see the strengths and weaknesses that the warchief - or the bodyguards - have assumed as they've levelled up throughout the adventure. This is where your strategies are born. You don't want to take on a fully powered warchief and his bodyguards directly - although you could if you really had to. Instead, you're encouraged to pick a warchief who has interesting weaknesses, kill or win over the bodyguards, and then take things from there as you lure the big guys out.

Each choice you make spawns a dynamic mission within the game world itself: it's clear that your strategising has down-on-the-ground tactical consequences. You might turn a bodyguard and then choose to level him up a little before sending him in to betray his boss, for example, and to do this you might need to ensure the bodyguard in question wins a territorial face-off against another Uruk captain somewhere.

It's clever stuff: follow the waypoint marker to the spot where the face-off's going to happen, and, at this juncture, any of the weaknesses that you might have exploited to win over your bodyguard suddenly become weaknesses that you need to defend him against in the ensuing fight. He'll be hammering away at a foe in the middle of a muddy field somewhere, you'll be watching from a nearby perch, and you'll suddenly remember: oh, wait, my guy's afraid of fire! I'd better keep his enemies away from any torches by arrowing them to the floor with my bow. Or maybe I could just drop down and give everyone a kicking up-close?

Bringing life to all this hierarchical meddling is a game world that feels gloriously alive with consequence, intended and otherwise, and filled with simulations and systems that you can tinker with. The Uruks like to wander around in packs, and so do those caragor, which you can wraith-power into obedience and then use to cause chaos. You can pick on footsoldiers to either pump them for information that will fill in gaps on the army screen, or you can turn them to your cause and then call them in to even the odds when a battle is going badly. Throughout this stuff, Shadow of Mordor takes its aesthetic cues from the films - and that goes as far as adopting their interpretation of the Uruks as gnashing, snarling cockneys forever spoiling for a fight. It's a bit like playing through some infernal mod based on Greg Wallace. But with fewer buttery biscuit bases.

The Nemesis system is so exciting that I'll be interesting to see how it fits into the wider game without overpowering it. Already, though, there are promising signs that it works well alongside the parkour and the combat and those far more familiar elements that Monolith's borrowing from elsewhere.

Perhaps fantasy fans should find this the most familiar element of all, in fact, drawn from a tradition that lurks far closer to the heart of Tolkien's stories than either the Batman Arkham or the Assassin's titles. When you get down to it, the Nemesis system is a kind of next-gen dungeon master, laying out the possibilities, keeping a close eye on your actions, and then making sure that, regardless of the outcome, whatever emerges feels like a story. Derivative as it is, Shadow of Mordor could be the most interesting Middle-earth game in years.