Local multiplayer is back, but is it here to stay?

The creators of Towerfall, JS Joust, Spaceteam and Turnover speak out.

The future of games, for years now, has been connected. This year's biggest blockbusters - from Titanfall to Watch Dogs to Destiny - are about bringing people together online, weaving players' experiences into one another's in new and pervasive ways.

There's another type of connection that was feared lost in the online swell, though: the thrill of being together with friends in a single room, huddled around a single screen and revelling in a single game.

"I think online kinda killed it for a while," says Matt Thorson, who developed the frenetic multiplayer game Towerfall, and is part of a wave of developers driving a resurgence in local multiplayer. Thorson believes that 'online' has become so synonymous with 'multiplayer' that some gamers behave as though nothing else counts.

"Online play is so much more ubiquitous now and so much more what players expect," he says. "Local multiplayer is a way of playing that's just so much harder to set up. Players don't even think about it any more. I know a lot of people when they talk about Towerfall say, 'This game doesn't have any multiplayer.' That's bulls***. It's like, 'This game does have multiplayer, it's just not the multiplayer you're used to.'"

Thorson's part of a generation of developers raised on the likes of Smash Bros., GoldenEye and Bomberman, all of whom are now making games in the mould of their childhood favourites. For them it's as much about rekindling the intimacy that's been lost with the rise of online as it is about rekindling youth.

"Social games aren't really that social," he says. "You're just sending people messages to give me coins or whatever, but you're not actually interacting with another person. Local multiplayer feels like true social gaming to me.

"It can be like an icebreaker for a group of people. Like if you're at a party and you don't really know anyone, you can play a local multiplayer game against them and it's just another way of getting to know them. It's an excuse to have a more intimate interaction than you'd normally have with a person in a public space. I think that's a really cool feeling... I know I have friendships that were formed completely around local multiplayer games."

Henry Smith, creator of co-operative phone and tablet game Spaceteam, is another developer trying to rediscover something that he feels has gone missing.

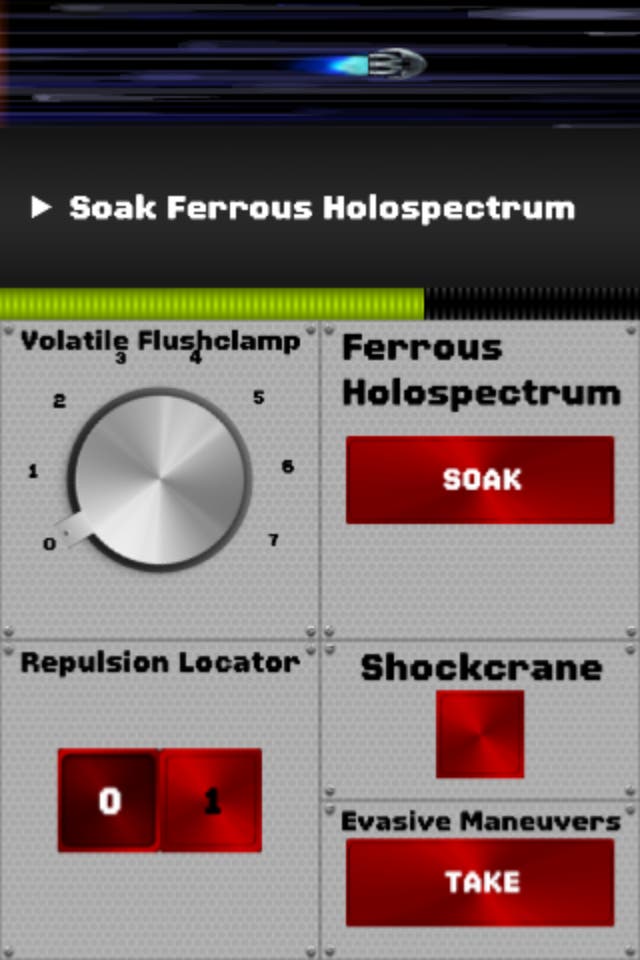

"I think people don't realise what they're missing," he says. "There's been a resurgence of board games, too, over the last 10 years or so... People are getting used to playing with people in the same room again. Online multiplayer is cool in its own right, because you can connect with people you don't see every day and make new friends online, but I think something's getting lost there because you're not interacting with people immediately around you. Spaceteam gives you an excuse to shout at your friends and pretend you're on a spaceship made out of cardboard boxes."

Smith suggests that gamers as a group - perhaps the sort of people who played GoldenEye together on a couch when they got home from school - have lost track of what made those experiences special, and that perhaps this is simply because of the social circumstances that surround growing older.

"It lets people be kids again, and I think we've forgotten how to do that as a society. People who make games are getting older and older and maybe losing touch with some of that fun that originally drew them to the medium. Now it's being rediscovered and people are remembering how they became excited about it in the first place.

"I've always tried very hard not to grow up and to maintain that sense of wonder and excitement, which I think is missing from a lot of people these days."

Johann Sebastian Joust, a game famously played without using a screen - where players wielding PlayStation Move controllers face off in time to a selection of baroque music - has been a source of wonder and excitement at gaming events for years, before finally finding its way into homes thanks to the recent Sportsfriends compilation.

The game's creator Doug Wilson is another in thrall to the glory days of local muliplayer, and in particular the Nintendo 64, a console that sported four controller ports as well as games such as Smash Bros., Perfect Dark, GoldenEye and Mario Kart.

"That was like the local multiplayer console," he says. "There's a rich history of this stuff in gaming. Like tabletop gaming and sports. Just gaming in general. It's just a well-enjoyed thing, playing games together with people in person. But I guess for economic reasons a lot of the triple-A companies over the last 10 or so years have focused on online gaming, especially with the rise of MMORPGs and consoles once they got network features."

Melbourne-based Chad Toprak is creating the event-only game Turnover - a competitive 2D platforming take on keep-away where gravity is relative to the side of the screen you're standing on. As such, to play it properly you need it projected on a floor or ceiling. Toprak, it turns out, is also getting a PhD in local multiplayer (you can do that in Australia), and believes that the genre is rising because games are easier than ever to develop.

"I think it started with games becoming more accessible not only to play, but to make as well," he suggests. "The tools are easier to use, distribution's easier - this whole indie movement carved a space for local multiplayer to exist.

"It was bound to happen. We came to a part in history where it needed to happen. It was kind of a response to the current state of video game culture," he adds, noting that the local multiplayer resurgence bears a striking resemblance to the New Games Movement in the 70s in which people started playing physical games and street games in public.

"The New Games Movement started off as a political movement that was kind of geared towards protesting the Vietnam War. There were a lot of hippies coming together and playing games to protest. At the time, playing games - or just playing - was something that was a child's thing. So that brought a lot of ideas and philosophies - like adults playing alongside children. At the time that was weird, because adults didn't play games, or weren't supposed to play games. That kind of broke that."

Toprak sees the move to local multiplayer as a cultural shift of indies rebelling against the status quo. "I think there's a permission culture within society. They wait for things to happen. They wait for people to give them permission to do something," he states. "I think one thing that indie games and this new arcade movement is doing is lifting away this toxic permission culture and allowing people to just do it. You don't wait for someone else to do it. You want something to happen, or something to exist, you just make it happen yourself."

This bold mentality is shared by all the developers I talk to. Toprak's game can't be played well on a standard TV screen, JS Joust doesn't use a screen at all, Spaceteam's gameplay mostly happens outside the screen as panicking players communicate verbally and physically, and Towerfall? Towerfall may seem like a relatively traditional competitive 2D platformer on the surface, but Thorson made one cunning move with it: he didn't include online play.

There are technical reasons for Towerfall's lack of online play, of course - latency being the main one - but there's a much greater reason, Thorson suggests: if online play had been included at launch, people would have defaulted to that because that's what they're used to. In turn, they would have had a subpar experience.

"People would doc points on reviews for [Towerfall] not having online, but I think if I did have online the review scores would have been even lower," he says. "Imagine that your first Towerfall experience was online - and let's face it, that would be most people's first experience, because most people don't have friends over when they buy a game - and you're playing against a total stranger, one on one probably, and you had like 60 milliseconds of ping both ways. It would be unresponsive and the person you're fighting wouldn't give a **** about you. That's completely different from Towerfall now."

This 'missing' feature actually became a feature of its own. "I'm glad it launched without it. Because people now know what Towerfall's about. If I could add online, and I could do it in a way where I felt the gameplay was still good, I think I would. More people playing the game is a good thing. But I think it will always be known that local play is the way to play Towerfall."

So far the infrastructure for playing these games is there, even if it's not as prevalent as it could be. Towerfall sold best on PlayStation 4 despite the console's recent launch and the fact that few games in its library make use of having a third or fourth DualShock 4 lying around. Spaceteam has been downloaded 1.7 million times, but its voluntary payment structure failed to raise much money. It's not clear yet if Sportsfriends has done well, while Turnover isn't out yet.

There has been some success, then, but it is not a foregone conclusion that this renaissance in local multiplayer gaming will continue. Right now it's coming back to the living room, but will it grow outside of that? Will the arcades of the 70s and 80s rise again?

Toprak is optimistic. He's taking a Field of Dreams sort of approach to his event-only games: if you make them, they will come. He hosts a recurring event in his home town of Melbourne called Hovergarden, where he exhibits indie games in public spaces.

"One of the things that it's trying to do is help make games a lot more inclusive," he says. "It's trying to get games to appeal to a broader audience - not just to 'gamers', but with the general public. With Hovergarden we host all our games in public spaces, so we can interact with the public as they're passing by. We get a bunch of people who are like, 'Hey, what's going on here?' And we get them to play, and they're like, 'Hey, this is awesome! I never thought games could be this fun!'

"My vision for local multiplayer is that we get so uncomfortable with the [existing] things we make that things like Spaceteam and Joust and Roflpillar and Turnover become viable. That we all start making these games and we collectively find a way or a space for these games to exist, to sell."

As such, he's hoping his propensity for exhibition-only games will inspire others to break free of the "permission culture" he speaks of. "For the longest time I've been frustrated with making very traditional video games that aren't really breaking any conventions or pushing any boundaries, and I try to encourage designers around me to at least locally step out of their comfort zone and try something different."

JS Joust's Doug Wilson, who made a name for himself developing experimental exhibition games, isn't as positive about mainstream culture embracing video games as an inclusive, public activity. He suggests that these sorts of event games are usually funded by academic grants, young indie devs trying to get attention and exhibition artists.

"I'm a little pessimistic," he says of the festival circuit ever reaching critical mass. "I think things are going to grow, but it's going to be a very long process... I think for the really radical, event-based stuff it gets trickier."

"I still don't think I could have released Joust on its own on PlayStation," he laments. "Even Sportsfriends was a reaction to how difficult that would have been to market. Conceptually I like the idea of Sportsfriends, so it wasn't just about the economics, but for any of us it wouldn't have been cost-effective to to have developed our small little games."

So maybe festivals and arcades aren't the place to sell these leftfield games to the wider public. But what about as toys?

"It's much easier to imagine selling something in a box," says Wilson. "One could imagine a strange take on Johann Sebastian Joust as a toy that you buy at Walmart. We're used to local multiplayer with board games. For whatever reason we're not used to that with video games. Which is interesting to me. Why are gamers complaining about spending $10 on Samurai Gunn or whatever, when no one would complain about buying the Battlestar [Galactica] board game for $60?"

Yet financial stability is only part of the reason Wilson is getting tired of the exhibition scene. On an expressive level, he's grown weary of spending ages developing projects that could only be experienced in very rare circumstances.

He notes that one of his exhibition games, Beacons of Hope, was probably more interesting than JS Joust, but the requirements to set it up were much steeper. The game is played in a pitch-black theatre where 15 or so people crawl around looking for three Move controllers to activate. Upon activation, they light up and emit music (by Proteus' composer David Kanaga no less). Turning on all three wins the game. The problem is that two of the players are 'monsters'. These players hold glowing red Move controllers that light up and play scary music when they move, but turn off when staying still. Since the room is shrouded in darkness, players don't know when a 'monster' is nearby until they're right on top of them. Turning on a beacon is also risky as that will alert the 'monsters' that there's someone over there.

It sounds amazing. It probably is amazing. But it requires a pitch-black theatre, five Move controllers, and upwards of a dozen people. As a result, Wilson's only had three opportunities to run it. After a while he simply wanted to share the fruits of his labour with a wider audience.

I ask if he believes we'll get to a point where these sorts of setups could be commonplace, ala laser tag. "Laser tag is actually pretty fun, but culturally it has less social capital these days. Can we have a newer, fresher, cooler laser tag aimed at adults?" he ponders. "I don't know, but I'd love to design something like that."

Events in public spaces will undoubtedly be popular with the small communities that embrace them, but by its very nature local multiplayer is constrained to these kinds of small-scale situations, so it often takes something very special (Wii Sports springs to mind) with a lot of marketing capital to punch beyond that. Toys or dedicated spaces might be a viable route, but it seems fanciful to suggest that indies like Doug Wilson will want to go to all that trouble. As he says, he's mainly interested in designing something like that. Perhaps licensing will prove to be the answer, should an eagle-eyed toy manufacturer suddenly take interest.

In the meantime, though, games like Sportsfriends and Towerfall are setting a strong example for anyone who does choose to follow, reminding everyone who plays them that playing games together in the same place is one of the most enjoyable ways to spend time with friends and family. Wilson believes that's the important thing.

"Sportsfriends is kind of an ideological project," he explains. "Part of the reason we wanted to put these games on console and really get the name out there is not purely an economic thing, but to take this stance and say to the world, 'Local multiplayer is fun! It's worthwhile! It's worth paying for! It's worth buying controllers for! These games are great!' I would say that's what some of us are trying to do: to change that conversation and that culture.

"It's a long, slow road," he adds. "But I think it's one worth traveling."