The making of Match Day

A funny old game.

"I don't like the FIFA games. I don't see the point in being able to see the players' nostril hairs," mutters Jon Ritman, a mischievous glint in his eyes. The creator of the legendary Match Day games on the ZX Spectrum is sitting opposite me in his local curry house - and is obviously not a fan of Electronic Arts' enduring franchise.

"I was in my local software shop when the first one came out and the guys working there knew I'd done football games in the past, so were keen to show it to me. I started playing and was thinking, there's something wrong here, I just don't get it." Ritman pauses for dramatic effect and takes a swig from his pint of Kingfisher. "So I shut my eyes, and scored twice in under a minute."

Just 10 years earlier, football games were considerably different, especially visually. The 70s had inevitably produced a whole bunch of Pong clones dressed up as 'soccer', and early cartridge-based systems such as the Atari VCS didn't offer much more. Then came the home computer invasion of the 80s and one popular game in particular on the Commodore 64.

"Everyone remembers International Soccer," says Ritman of Andrew Spencer's 1983 classic. "I'd seen it in shops, but actually, not being particularly bothered about football, never played it." Ritman was working on what would transpire to be his final game for Artic Computing, Bear Bovver, when he visited a computer game trade show. "There were several distributors there and being freelance and having the luxury to choose my projects, I asked them all what they were looking for." The reply was almost unanimous: they wanted International Soccer on the ZX Spectrum.

Ritman would soon be working on Spectrum football. In the meantime, Artic Computing was continuing to frustrate him with its lack of promotional prowess on Bear Bovver. "The Artic adverts were just pictures of a row of cassettes on a bookshelf," he says. "And I'd said let's do something different. So I persuaded them to do a teaser advert with this bear hanging off a ladder and no writing. We slowly introduced words and more information and I remember going into shops and hearing people talking about it. But they took four months to put it on the shelves, by which time it was too late."

Then, two weeks after Ritman had begun writing Match Day, having already left Artic, he was attending another computer show at Alexandra Palace. "I was wandering around and David Ward came up to me and we started chatting. Inevitably he asked what I was working on." When Ritman began to explain his current project to the Ocean Software boss, he suddenly realised he was next to the Artic stand where its new game, World Cup Football, was being demonstrated. "I pointed at it and said, 'It's a football game and it's going to be loads better than that,'" he laughs, "which was a bit cocky because I was only two weeks into writing it and it didn't even have a scrolling pitch at that stage." Ward must have been suitably impressed though, because Ritman received a phone call just a few months later.

"He phoned me up and asked how the game was going; I told him it was nearly finished." Without hesitation, Ward offered Ritman an incredible £20,000 upfront as a royalty advance. "It was more money that I'd ever dreamed of. So I said, yeah, okay." It wasn't long before Ritman, having already found employ as a TV repair man for Radio Rentals, was making more money out of programming in the evening than he was working in the day. A change of main career was an easy choice.

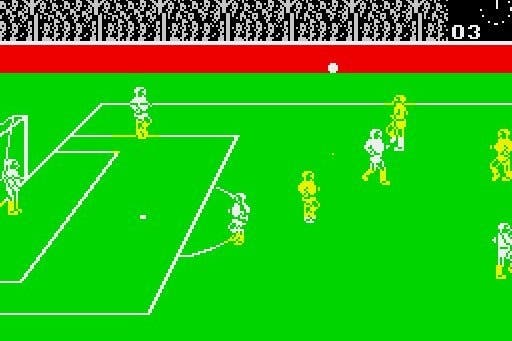

Despite Ritman having never played International Soccer, it had the same viewpoint as Match Day (horizontally scrolling, a pseudo-3D side-on view as if sitting in the dugout) - surely that was an influence? "To be honest, it never occurred to me to do it from any other perspective," claims Ritman. "As that way allowed you to use three dimensions, you can see more of the pitch and it gives you the ability to pass where you want to."

As Ritman had yet to meet his design cohort, Bernie Drummond, all the in-game graphics were from his own hand, although some of the sprites may have been - ahem - borrowed from his previous game, Bear Bovver. When he finally got around to sampling the dubious delights of World Cup Football, it made Ritman even more determined to improve upon the Artic game.

"The first thing I noticed about it was the lack of solidity in the players," he notes. "You could run right through another player and take the ball off them. That struck me as really dumb, so right away I wanted solid players. I also wanted larger sprites so you could see distinct body areas and use them, such as being able to head the ball."

Although Ritman refers to himself as "no artist", this wasn't the most worrying aspect for him as he put Match Day together. "I really didn't know how I was going to do the AI," he grimaces. "I kept putting it off, working on other elements of the game." With the coder adamant the game should have a computer opponent, eventually he reached a point where it simply needed to be done before development could progress any further.

"I sat down and my first AI routine was about 10 lines of code, which basically said: 'If you haven't got the ball, run towards it. If you have got the ball, kick it up the field." Despite sounding more Harry Redknapp than Jose Mourinho, the routine did its job. "The computer scored against me in under a minute. I was literally crying with relief!" laughs Ritman. Naturally the code was refined further, especially in the area of which footballers the player takes control of. "That was a little complex, who you had control of. I had to compute where the ball was going to be and who and when to then hand control over to."

At this point Ritman assembles the salt and pepper pots in front of him in the time-honoured method of explaining football. Except this time it's not the offside rule, but the clever code that the ZX Spectrum used to decide which player is controlled and help gamers control the one they wanted to.

"When you passed the ball, the computer worked out who was the nearest player to where the ball was going to land, but it may be a different player to the one the human player thinks as the computer is judging it by exact pixels," explains Ritman. This would invariably result in the correct player, as chosen by the computer, running away from the ball as the human thinks it has control of another player.

Ritman's solution was to implant a code that theoretically doubled the distance between the ball and any player moving away from it, effectively giving control back to the player of the sprite that they wanted to control in the first place, all within the space of a few frames. It seems an extraordinarily complex way of creating the right result, but it worked, and even the most ardent of Match Day fan would have struggled to notice. "That was the idea," says Ritman proudly. "It was really quite clever, even if I do say so myself."

In terms of gameplay, Ritman was adamant that Match Day be a football game where the player could actually string together a proper passing move. "It never crossed my mind to make the game with a general pass button that just let the computer automatically pass the ball to the nearest player. Nobody had even done that in 1983."

Ritman's preferred method was simple, yet effective: you faced the direction you wanted to kick and pressed fire. Doing this while moving resulted in a lobbed pass; while stationary, a ground pass. The players themselves reacted well and could turn and move relative sharply. But what happened with the goalkeepers?

"Ah, the goalkeepers," murmurs Ritman. "I didn't really know what I was doing with them. I couldn't see any way to control them other than diving and didn't think it would work. They were a bit s***, weren't they?" I try not to nod too much as I ask the man opposite me whether there was anything else he felt wasn't up to scratch.

"Just the fact that I had more ideas but not enough time or realisation to get them in. I did actually fill the memory out with the main game, so there wasn't much room for anything else, but I'd have loved to have had sliding tackles, penalties and more speed. To be honest, I could have done another football game straight away and made loads of improvements. I didn't get the chance for another three years as I'd seen this amazing 3D game called Knight Lore and wanted to do something like that."

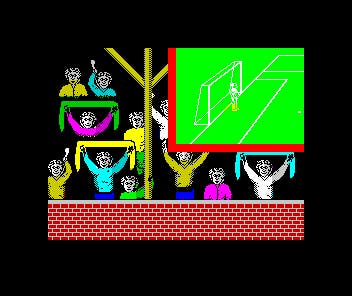

In addition to providing Ritman with any equipment and support he needed, Ocean Software was busy acquiring a licence for the game. Whether they realised it or not, it ended up with just the theme tune to BBC's Match Of The Day which burped and squeaked interminably through the weedy Spectrum 48k speakers. The name was altered to the snappier Match Day and the game squeezed out just in time for Christmas 1984, receiving rave reviews in practically every computer games magazine. Newsfield's Crash, despite the game narrowly missing out on Smash status with a score of 86%, even organised a tournament with readers phoning up and proclaiming their biggest win against the computer.

"They phoned me and explained what they were doing and offered to put my girlfriend and I in a hotel for the night as well. And we just went and played Match Day all afternoon - myself, Bernie Drummond and Chris Clarke - with all these lads that had won the competition."

One of the boys facing the Match Day team that day was 14-year-old Paul Johns. "I was brilliant at Match Day, it was 'my' game where I just ruled supreme and always thrashed my mates at it," says Johns. "So I phoned Crash up with my score (21-0) and a month or so later got a letter inviting me to the competition."

Knowing all the tricks to the game served the young Johns well; he easily trounced Drummond and Clarke before the sternest challenge of all: Ritman. "I started off well," he remembers, "and the game was 2-2 with about 10 minutes remaining when I had a shot and the ball got stuck under the goalie." This was an infamous bug that could only be resolved one way, by resetting the computer. When the match was restarted, Ritman came out a comfortable 3-1 winner. "He was brilliant at the game and you could tell he just knew everything about it."

It's now almost 30 years since the release of Match Day. How does Ritman look back at the game today in terms of his own career? "It was where I really began to learn to code, especially in terms of AI. It also got me into football, setting off a series of football games and taught me an awful lot about the rules of the game along the way."

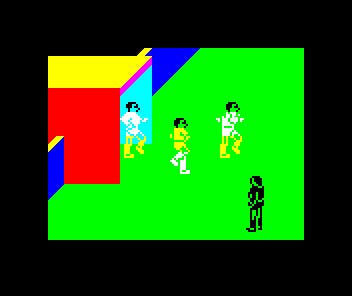

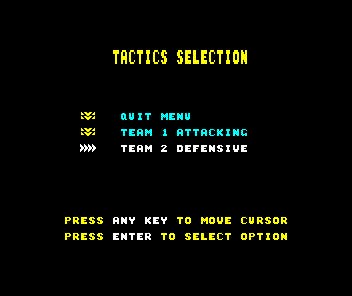

Match Day's 8-bit sequel included many of Ritman's improvements, such as different-strength kicks, volleys, jumping, a league format and a cheeky little back-heel. The diamond deflection technique, trialled in a more primitive form in the first game, became a key element to the sequel, creating the ability to 'one-touch' pass or flick the ball on. "For me, a football game has always been about passing, being in control of that totally and being able to pass into space; that's where the big plays are made. And while the game has to be playable and easy to get to grips with, I never wanted the player in any of my games to be able to score within the first few minutes of playing. My style was that when you play you learn and the joy comes from the mastery of the game."

To paraphrase Ron Atkinson, I would not say Match Day is the best series of football games on the ZX Spectrum - but there are none better.