"It's not historically accurate!"

Why arguing against women appearing in games to preserve historical accuracy is silly.

Recently I wrote about the realisation that I am sexist and how I'm trying to change. The response was fascinating. OK, a few people were so upset that I want to respect other people's humanity that they threatened to leave the site forever, but I also received lots of thoughtful messages, in comments and by email, leaving me with lots more to think about.

One of the ones that stuck out came from a reader called Juliane, who told me about something that always irks her when this subject comes up. It's the old argument that female protagonists don't make sense in a lot of games (or books or movies or comics or whatever) because their presence isn't historically accurate.

Juliane had a good point to make about this, but before we get into it, let's first take the opportunity to consider how selective the "it's not historically accurate" defence is whenever it's levelled at people who advocate for the addition of female characters to video games (or indeed any character that isn't white, straight, male, vest-owning).

Take Assassin's Creed 2, a wonderful game that is praised for its historical adaptation. Rightly so. Assassin's Creed may be a series of rollicking adventures about swashbuckling heroes like Ezio Auditore, but I have always respected the way it acts as conservator to the eras it pootles around in, erecting beautiful digital monuments to real-life masterpieces like St Mark's Basilica or the Colosseum and introducing them to us slowly and deliberately, so that we might absorb their splendour as we crawl all over them looking for trinkets.

But the series has always been pretty flexible with those supposedly important details, too. For example, did you know that when the Pazzi family attempted to murder Lorenzo de' Medici in real life, they did it inside the Duomo di Firenze? In Assassin's Creed 2, it happens on the steps outside, presumably so that when Ezio intervenes and spirits Lorenzo away through the streets he has more room to manouevre, and he can do so without the programmers and level designers having to cope with the complicated technical transition from building interior to running around outside (something which they are only now becoming confident to handle on next-gen hardware with Assassin's Creed Unity).

This change is one of hundreds of examples of the artistic licence the developers embraced to get the job done. Is the game worse for this lack of accuracy? And for that matter, is the game worse because it believes bales of hay can save your life if you jump into them from a height of several hundred metres? Of course not. Accuracy isn't always fun, which is why even the games that draw on real history take liberties with it in order to make what they do practical, accessible and interesting.

None of this was why Juliane wrote to me about the historical accuracy defence, though. Juliane's objection was simple: written history isn't accurate.

We all know this, of course. Written history is only a record of events set down by human beings, and human beings are fallible. But I found it surprising how big a difference there was between my accepting that history as I know it is flawed and my comprehending the ways in which this is the case, many of which are depressing on the one hand and sort of darkly comic on the other. Maybe you'll have a similar reaction.

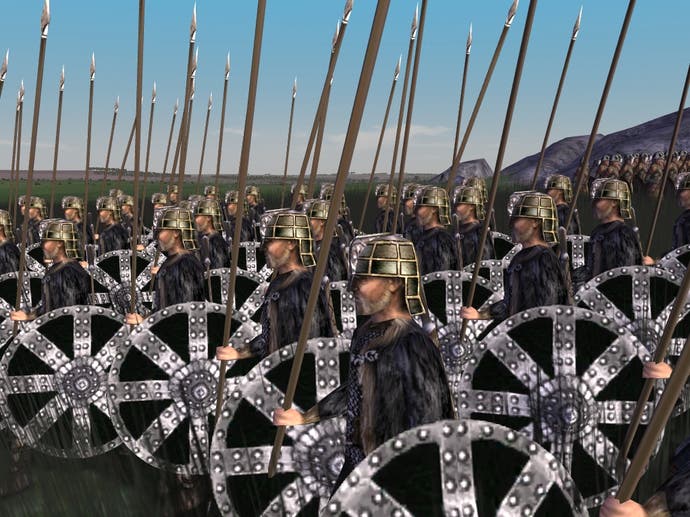

Did you know, for example, as I didn't, that academics only recently started to accept there were actually really quite a lot of Viking women roaming around pillaging? And that they probably fought just as much as the men? As Kameron Hurley noted in this essay Juliane pointed me to, which cites research conducted by Shane McLeod of the Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies at the University of Western Australia, the reason nobody thought this previously was that whenever archaeologists uncovered the grave of a Viking buried with a sword, they assumed it was a man. Because sword. A few years ago it occurred to someone to check.

Sometimes history is wrong because of mistakes, then, but a lot of the time it's just biased, which is another concept I have always found easy to accept without really considering it more deeply. We're used to being told that history is written by the winners, but historical accounts of influential periods were also often written by men, and men have demonstrably always believed that the things men do are more important (usually more through instinct than nefarious design, I suspect, although there's plenty of that around as well).

Want an example? Well, we've done gaming's great friends the Vikings, but this piece by Australian fantasy writer Tansy Rayner Roberts, linked by Hurley, has another good bit about one of gaming's other go-to groups, the Romans.

"Most of the history books looking at Roman state religion were clear that women's participation in the religious rituals of the state was probably less important or politically relevant, because women were excluded from making blood sacrifice. This was used as evidence, in fact, that women weren't that important to politics in general," she explains. "However, more modern and forward-thinking scholars pointed out that in fact the only reason why we assume blood sacrifice was an essential and a more politically important religious rite was because it was restricted to men."

Vikings, Romans - whatever the context, written history is often mistaken or biased in key details. And when it comes to the creative work that taps into them, those mistakes and biases act like fault lines, sending shockwaves of misconception through any resulting work.

If historical accuracy is flawed, though, perhaps it's still important to perpetuate people's notions of historical accuracy in order to create compelling art? After all, one of the key reasons the Assassin's Creed series is so stirring is that it's always steeped in familiarity, if not accuracy - buildings you've seen, people you know about - and it's that familiarity that helps you to accept the much more outlandish things it does, like jumping into those bales of hay (or the space-wizards meta-story). Perhaps women shouldn't be included in key roles because it makes the games less relatable, if not less accurate?

It sounds like a nice dodge, but it's a weak one, if for no other reason than sticking to these narrow formulas - like the idea that women don't belong on the battlefield or in politics - quickly leads to creative stagnation.

Take a look at the world of TV, where it's no coincidence that shows like Battlestar Galactica and Game of Thrones, in which women are generally portrayed as regular people with hopes, dreams, flaws and all the rest, seem so different and interesting and run for many years, while other more generic sci-fi and fantasy shows disappear a lot more quickly.

As Tansy Rayner Roberts puts it, "if your political system is inherently and essentially misogynist and that is essential to your world-building, then throwing a few women into that system to see what cracks first is actually the most interesting thing you could do. Like with science fiction where science goes wrong is the most interesting plot." When you make something like Battlestar Galactica or Games of Thrones instead, you simply have more perspectives to work with, resulting in a richer mix of characters, motivations and outcomes. If only more games were like that.

However you try to co-opt history or perceived history into the defence of games that lack diversity, then, it doesn't really work. A little historical adaptation isn't a bad thing, because there really is something wonderful about a generation of gamers growing up crawling around the Castel Sant'Angelo, but it's important not to get too carried away, whether you're creating something yourself or defending something that's been created by someone else. Written history is just as much a reflection of the hopes, limitations and prejudices of the time as all art, and carrying those flaws forward through the ages, whatever the rationale, only makes the things we love less interesting - and I very much doubt that's what any of us really wants.