It's early days, but Sunless Sea is already fascinating

Fisher, German Bight.

Why has nobody made a video game of the Shipping Forecast? Because it's a five minute weather report broadcast a few times a day on Radio 4? Or because it's just too brilliant, and because it already does what most video games wish they could do - yank you out of your day-to-day life and transport you somewhere that's both coherent and completely fantastical?

If you're a sailor, the Shipping Forecast probably only tells you what conditions are like around the British Isles. (Spoiler: they're rubbish.) If you're not a sailor, however, the Shipping Forecast turns you into one. Further more, you sail not to Dieppe, say, but deep into the imagination: to Dogger, which can only be a vast, Tolkienesque statue of a terrier, hundreds of meters high, feet together and snout proudly thrust into the grey skies and the driving rain. To Cromarty, a splintered island of salt crystals, slowly fragmenting in the wake of a giant eddy. To Fitzroy, where lightning sparks over cornfields filled with thousands of spinning windmills, their blades almost - but never quite - touching, alive with the tubular glow of St Elmo's Fire.

Maybe somebody is making a video game of the Shipping Forecast. Failbetter Games, best known for delicious and atmospheric read-'em-up Fallen London has recently hit Steam with its Early Access build of Sunless Sea. This is a Roguelike, of sorts, in which you commandeer a boat, gather a crew, and set off from the docks of the midnight city itself to explore the vast, subterranean ocean that lies beyond it. Failbetter's said the game's a bit like Don't Starve and a bit like FTL, but it's not really. Mostly, it's a bit like Sunless Sea. It's still coming together, but the pieces that are already in place are brilliant.

This is survival exploration at its most distanced, and its most terrifying. Leave port and it's just you and your boat, which seems tiny and fragile as it chugs along, far below your high vantage point. For your first few trips, it's genuinely disorientating: crazy landscapes float past you and the screen is a motley of gauges and dials. In truth, on the most simple level, Sunless Sea is pretty simple indeed: cover as much ground as you can while making sure you don't get killed by an unmentionable horror or run out of resources. No fuel and your boat will be left adrift forever more. No food - or too much terror - and your crew will go nuts and eat each other.

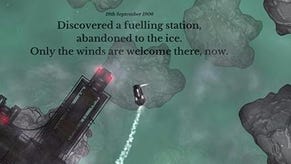

During those first few hours or so, it's a mainly cartographic pleasure, as the thick-lined art picks out little jetties and paths across each isle you discover, while the glorious glowing font announces a succession of names that would make the BBC meteorology department desperate to grab a mic and announce a flood warning. Moody's Light, Thornwell Croft, Patrick's Lot, Gaider's Mourn. Image and text mesh wonderfully even at this point: the Phosphene Bleaks are a chewed-up scattering of smoking stone, and you can almost feel the grain of the bitter air that surrounds them. Meanwhile, the sea itself is a constant textured pleasure. Low Barnet is so very low, for example, that its domes are entirely under water. Why? What did they hold? What did they do?

This teasing half-light that Sunless Sea seems to exist within will be no surprise to veterans of Fallen London. Failbetter's most famous game has always been illustrated, but when it relied on language to do a lot of the heavy lifting, it still employed its sumptuous prose to tell you less - always ever so slightly less - than you needed to entirely orient yourself. Now that the balance has shifted somewhat, Failbetter's still doing much the same thing in new ways. "The zee-bats cry out," reads the text in your log book. "They are nothing like birds." Isn't that so much better than being told outright what they are like? Similarly, when it comes to the visuals, the more you see, the more you wonder about what you cannot see. What's inside that strange factory located at the edge of a peninsula in the middle of the briny deep? What lies beyond the feeble pools of light cast by each buoy?

Explore a little further and you'll get into fights - against those zee-bats, against other ships, against horrifying entities from the deep that have names but still defy easy classification. Whatever happens, battling shows a studio that's used to telling tall tales through a series of elegant missives is surprisingly at home with real-time combat.

It's ship-to-ship stuff, or ship-to-giant-toxic-narwhal at least, and to attack your enemy with your weapons you have to first illuminate them with flares. You have to keep an eye on your own safety, too, evading incoming salvoes and repairing your hull when you can. What this comes down to is the selection and employment of a series of skills, each of which brings its own cooldown. The battle's barely animated, but that doesn't matter: the magic happens in your own head, just like it always did on the streets of Fallen London.

There's more of Fallen London to Sunless Sea than I was actually expecting. As you steam about, adding new locations to your log book and beating up giant crabs, you'll find the option to dock at certain ports, where adventures play out much as they do back on Ladybones Road - via short snippets of woozily evocative text and simple, heavy-risk decisions that might net you much needed provisions, or might absolutely kick you in the shin for your troubles.

It should be disorientating, this shift from real-time cruising to reading and weighing up options. In fact, it works thrillingly well. Take Hunter's Keep, "a clump of dark rock swathed in mist", which is currently to the north-east of Fallen London itself, but which could eventually be anywhere when the right beta build comes along and the map starts to shuffle itself each time you set out. On Hunter's Keep, you can choose to "present yourself at the house" (to use the same, wonderfully stiff sort of Victoriana that sees men "getting to their legs" in parliament in old Disraeli novels) and meet the sisters who live there. A maid with smouldering topaz eyes will introduce you: Cynthia, melancholy and pensive, Phoebe who's noisy, and Lucy, the cheerful one.

I had lunch with Cynthia, and it was not a pleasant lunch by a long stretch. A close inspection of her tangled hair suggested that bats might rest in it. I had a sense of blood on scented water. Ick, as Disraeli might have put it. I couldn't wait to get to my legs and return to the sea.

Still, I scored some supplies before I made it back to my boat. My men were slightly more terrified, and their mutiny loomed ever nearer, so it was a mixed blessing. In truth, though, what I'd really scored was a memory - a spooky sense of place and character that stands in beautifully for a wider narrative.

There are apparently about 100,000 words in Sunless Sea already, with many more to come. Failbetter's writing is rich and decadent: too much of this kind of stuff and you'd get a kind of Mervyn Peake syndrome setting in - brilliance that becomes cloying. The real-time nature of Sunless Sea allows all this to be broken up into manageable chunks, though. It enables truly writable writing where every sentence read feels like a collaboration. Killed some zee-bats? Into the pot! They really are nothing like birds.

Failbetter's Alexis Kennedy once told me during an interview that the Spelunky fallacy really annoyed him at times. You know, the idea, oft repeated around here, that the best stories in games are the ones you tell yourself. With Sunless Sea, Kennedy's small crew seems to be hitting an enviable sweet-spot, where the stories you tell yourself knit together so tightly with the stories you're told along the way that you can't hope to spot the seams. Anchor up, engine stoked. And away.