Blurred lines: Are YouTubers breaking the law?

From unmarked advertorial to paid social network promotion, Simon Parkin investigates the ethics and legality of YouTube.

John Bain received his first offer to create advertorial for his YouTube channel in 2010. "A video game publisher asked me to create a video about one of its titles," says Bain. "They agreed to pay for the coverage so long as I agreed to not say anything negative about the game." It was the first of a slew of such deals that Bain - better known to his 1.7 million YouTube channel subscribers as TotalBiscuit - has been offered, from posting a product link in a video's description through to elaborate ad campaigns. Bain was asked not to disclose the nature of the proposed sponsored content to his viewers. He refused the deal. "I don't know how I'd live with myself," he tells me. "It's taking your passion and selling it out for a small pay-cheque. It morally bankrupts you."

YouTube, the Google-owned streaming video service that allows anyone to upload their videos for public consumption, has created numerous cottage industries since its launch in 2005. Self-styled video game broadcasters are the service's most popular home-grown stars. 24-year-old Swede Felix "PewDiePie" Kjellberg has over 28 million subscribers to his channel, an audience that rivals that of America's slick-haired talk show hosts. In YouTube's earliest days, these presenters earned money exclusively through traditional 'pre-roll' advertising, whereby a 30-second advertisement would play out before their video. Here, as on television, the distinction between advertisement and content is made clear to the viewer. But during the past few years, the lines have blurred.

Susi Weaser works for Channel Flip, a Soho-based company that signs and manages rising YouTube talent, including some who specialise in video games. "We sell pre-roll advertisements for our clients whereby a specific advert is run against their video," she says. "But we also broker sponsorship deals and product placement in YouTubers' videos." The fee that Channel Flip's clients receive for this kind of deal is largely dependent on the size of their audience, the suitability of its demographic to the advertiser and whether or not they believe they will see a return on their investment. "The amount of money paid out varies wildly," says Weaser. "It's generally in the thousands of pounds, but it might be dictated by the number of times the YouTuber has to say the product's name, for example."

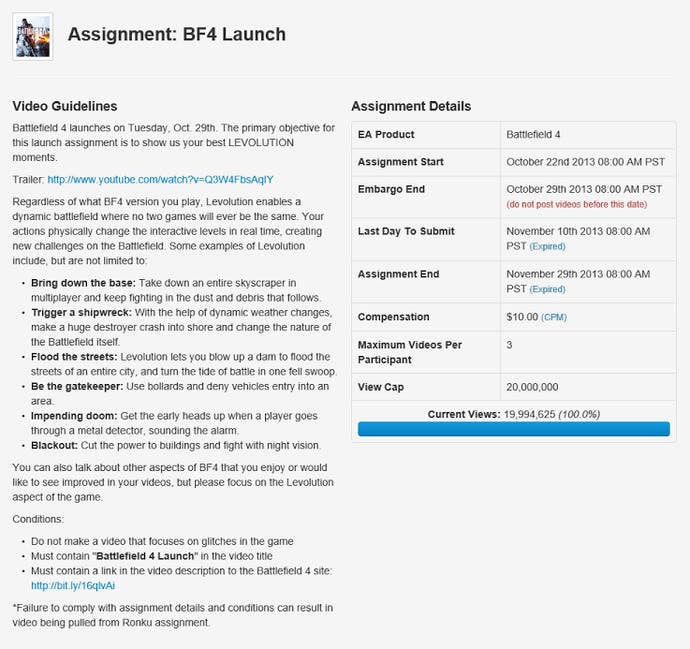

Some of the world's largest video game publishers offer similar sponsored deals to prominent YouTubers. Some even have entire divisions devoted to this work. EA Ronku is perhaps the best known of these clandestine programmes. The company invites YouTube 'influencers' to create videos of its forthcoming games on a commission basis. One participant, who asked to remain anonymous, was paid £10 for every 1000 views of the video he created for EA Ronku. In his case, the agreement was brokered on the proviso that he didn't draw attention to any of the game's bugs in their commentary, ensuring the game was presented in only its best light.

EA, which declined to be interviewed for this article, is not the only company to offer advertorial deals. According to one source, who asked to remain anonymous, Ubisoft paid a prominent YouTuber (who is represented by Channel Flip) £8000 to attend Gamescom in 2012 and create a series of videos exclusively about the company's games. In this case, the coverage is not labelled as advertorial. Ubisoft, in a statement provided to Eurogamer, says it does not request YouTubers to disguise the fact they have been paid for content. Bain believes that the majority of YouTubers and channels currently fail to disclose to their viewers when the game's publisher directly pays for content. "I've seen many UK sites and channels produce obviously sponsored content without saying so," he says. "But I firmly believe that if you are being paid to represent a company or its products as a YouTube personality or channel then you must disclose that relationship."

Clarity and disclosure is not just a matter of personal preference. Since 2009 any US-based YouTube videos that provide a paid-for endorsement of a video game must abide with FTC regulations and clearly state the fact. Some who work in the industry, however, believe there is no such law outside of the US. "There are no regulations in the UK," says Weaser. "There are only best practice guidelines."

But such views are mistaken: British law is unequivocal. Paragraph 11 of Schedule 1 in The Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations (CPRs) outlines a prohibition against 'using editorial content in the media to promote a product where a trader has paid for the promotion without making that clear in the content or by images or sounds clearly identifiable by the consumer (advertorial).' This law has been in effect since 2008. The Office of Fair Trading illustrates the point like so: 'A magazine is paid by a holiday company for an advertising feature on their luxury Red Sea diving school. The magazine does not make it clear that this is a paid-for feature - for example by clearly labelling it 'Advertising Feature' or 'Advertorial'. This would breach the CPRs.'

The reluctance of some YouTubers to clearly mark advertorial is neither new nor something that's unique to YouTube: magazines and newspapers have long wrestled with the word. Even if a piece of advertorial provides a truthful representation of the writer or broadcaster's personal opinion, the label acts as a warning to readers and viewers that, at very least, there is a risk of prejudice.

But for David Bond, a lawyer at of Field Fisher, a London law firm that specialises in technology, media and communications, the law applies to any YouTuber paid by a manufacturer to promote a game, just as it does a magazine or newspaper. "In every case the financial arrangement should be disclosed," he says. The repercussions for breaking CPRs can be significant. "The enforcement body may apply to a court for an order to prevent infringements of the CPRs," says Bond. "Breach of an enforcement order could be contempt of court which could lead to up to two years imprisonment."

***

Some YouTubers, with their vast and engaged audiences, have become kingmakers in the games industry, able to propel games to fortune-making stardom. Most attribute the success of Flappy Bird, the iPhone game created by Vietnam-based developer Dong Nguyen which rose to the top of the iOS charts in January 2014, to PewDiePie. Prior to his YouTube coverage the game was unknown. "I want to see games that may have languished in obscurity rise to the prominence that I believe they deserve," says Bain. "That's probably the most appealing part of my job."

But some YouTubers have begun to attempt to leverage this power for financial gain. One high profile indie game developer who asked to remain anonymous recounted how one of the largest UK-based channels offered to cover his game in exchange for a cut of profits. "It was a pretty straightforward offer," he told me. "There were no euphemisms or dishonesty, just a straight up offer to create content that drives an audience to my game in exchange for a limited duration cut of sales."

Yogscast is the most viewed YouTube channel in the UK with more than 7 million subscribers. The channel began as a two-man operation, posting humourous videos about World of Warcraft. In recent years Yogscast has grown to a sizeable commercial operation with a multitude of presenters (some of whom are ex-journalists). In 2012 Yogscast became a registered company with a business team that now offers revenue-share deals to game developers: a limited time cut of games sales in exchange for coverage. After initially agreeing to an interview for this article, the Yogscast senior management instead offered a formal statement, which they then posted as an 'open letter' to Reddit ahead of this article's publication.

In the statement Mark Turpin, Yogscast's CEO and business development manager, confirms that the company engages in revenue-share coverage with game developers. "We're working with a few selected partners on limited duration rev shares around our content covering the game," he said, revealing the team's name for the proposal as 'YogsDiscovery'. "We don't allow for any stipulations as to the content we release when working with publishers, our voice is always our voice," he added.

Regarding the disclosing of paid-for advertorial Turpin insists that the channel always includes "a written description below the video." Turpin refused to say when this became the channel's policy, but stated that the text the channel now uses to comply with regulations is the somewhat opaque line: 'A special thanks to [Developer/Publisher] for making this video possible.' Tuprin added that, "As our content doesn't go through any form of client approval it isn't qualified as an advertisement by the Advertising Standards Agency. That being said, they are satisfied by our wording and distinctions made from our other content."

Not everyone believes that Yogscast has gone far enough in its transparency with viewers. "A lot of us are not happy with what they're doing," said one YouTuber who asked to remain anonymous. "It reflects badly on all of us. It's not hard to find their sponsored content and it's not clear that this is what it is. Their audience is kids and they don't necessarily understand the nature of what's going on. They don't have to act this way; they have a huge audience."

The idea that a supposedly independent voice in the media would offer a developer coverage on the basis of a cut of the game's profits seems coercive. But many are giving this kind of deal serious consideration. "It comes down to how the audience would respond to hearing about this kind of deal," said the anonymous developer. "If viewers are suitably informed of the commercial interests involved, and accept them, then I think it's OK. I'll be watching how it goes down for the first few people to openly enter into these relationships before risking my company's credibility over it."

Some of the best-known YouTube celebrities offer far less than a commentated playthrough of a game to developers struggling to spread the word about their game. One PR agency, which asked to remain anonymous, tells the story of a YouTube celebrity who asked for a one-off payment to 'like' the trailer for one of the games that the firm was representing. "We were once approached by a prominent YouTuber outside the world of gaming who suggested we pay them £10,000 to 'like' a video," he told me - a simple action that would promote the video to the YouTuber's many subscribers. "We rejected it, but the feeling in the agency was that if they are asking for this kind of fee, then people are paying."

These deals feel dishonest to consumers, who might reasonably assume that a YouTuber chooses their subject matter based on the games that they are interested in rather than those from which they stand to gain financially. But for independent game-makers who now compete with thousands of other unheard-of games, there is clear financial benefit to employing a powerful YouTuber to the cause. Convince someone with a sizeable audience to cover your game and you have bought yourself invaluable coverage. "It scares me to think how much it would have cost to market my game to the audiences TotalBiscuit, Pewdiepie and Nerd Cubed alone brought to the game," says Mike Bithell, creator of Thomas Was Alone.

Despite the logic of the arrangement, Bain believes it is damaging. "The risk is that we end up with a situation where channels hold games to ransom and will refuse to cover a title unless the publisher offers a slice of the referral profits." Arguably, it's the large sums of money involved in the process that inspire these nested compromises. "The problem is you have an unregulated medium raking in shitloads of money whilst simultaneously being hailed as the maker-or-breaker of gaming," says Simon Byron, director of games at the PR agency Premier. "They wield great power and that can be seductive to some developers. I'd hope that people won't take up any of these offers - their channel risks losing credibility, which in the fickle world of online video is the only thing they have."

***

The most popular YouTube stars do not have to engage in advertorial. According to Business Insider, PewDiePie earns between $140,000 and $1.4 million per month from pre-roll advertisements alone. Bain's channel is also popular enough to earn a living this way. He does, however, accept sponsorship deals, but insists that he is always careful to make the nature of the coverage clear to his viewers. "I have built my reputation on honesty," he says. "To fail to disclose sponsored content would be the most grossly disingenuous thing I could do." More pointedly, perhaps, Bain believes that a failure to disclose such a deal might irrevocably damage his career. "I view my business in the long term," he says. "I've been doing this for four years and I intend to do it for 40 years to come. I have to protect my reputation."

Bain, with his army of subscribers, is perhaps less susceptible to corruption than lesser known YouTubers who hope to earn a living from their work. He believes that the rise of undisclosed advertorial deals is due to systemic issues. "This is a market in which ad-blocking software is on the rise," he says. He also points out that if a YouTuber agrees to advertise a product in pre-roll that is unavailable in some countries, then no ad will show to those viewers. "That's a significant part of what has caused the rise of 'influencer' videos," he says. "For most YouTubers, ad-based rates weren't sufficient."

For Byron, the risk is that a failure to disclose deals is not only illegal, it also risks eroding trust between viewers and YouTubers. "I've long thought that the relationship between a YouTuber and their audience is one of the most honest," he says. "But it feels like that honesty is endangered. At best, commercial deals are often only slyly acknowledged. Watch out for phrasing such as 'Publisher X asked us to get involved with...' That's usually a sign that money has changed hands. It should be made much clearer."

***

Unmarked video game advertorial content on YouTube is unlawful, but for some it is merely the latest manifestation of media corruption that is decades old. All media, from the elderly behemoth newspapers down to the humblest blogger, is increasingly susceptible to this kind of corruption as content is increasingly offered to consumers gratis, supported only by the single revenue stream of advertising.

Mike Channell, one of the presenters of Outside Xbox (a YouTube channel that, it should be noted, is part of Eurogamer's parent Gamer Network) believes that many YouTubers have been oblivious to the implications of their decision to run unmarked paid-for content. "In most cases I believe that it's ignorance more than malice that leads to these situations," he says. "Most of these guys don't have any experience or guidance with matters of ethics. They feel inside that they're not being corrupted based on their own moral compass, but what they perhaps haven't recognised is that perception and audience faith is just as important as personal justification. I'm absolutely convinced most of them care far more about their audience than a bit of extra cash on the side."

The repercussions for a YouTuber whose audience finds out from somewhere else that there may have been an advertorial aspect to the coverage can be severe. Jack Frags published a 30-minute explanation to his audience defending his engagement in EA's Ronku programme earlier this year. It's a spirited defence in which he argues that he didn't say anything that he wouldn't have had he not been engaged in the influencer programme. But as many in the games media know only too well, appearances are often as important as fact to a consumer audience who put their faith in your impartiality.

There have been times when the disclosure of sponsorship deals has backfired. During Microsoft's Summer of Arcade campaign in 2013, the company offered sponsorship to some prominent YouTubers in exchange for coverage of the games that were released as part of the programme. One YouTuber, VideogameDunkey, created a video in which he criticised one of the games, Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons. When Microsoft requested that he retract the video, he disclosed the deal to his audience, for which he stated that he was paid $750. The systemic failure to disclose the deals sooner hurt the game itself. "Those of us who covered the game later on, when it was released on PC, were accused of corruption," says Bain. "The public perception was that anyone who said anything positive about the game was paid off."

Nevertheless, for Bain, there is a distinction between journalistic corruption and the failure of some YouTubers to disclose advertorial content, even if they are part of the same continuum. "YouTube is far more vulnerable to brown envelope stuff than traditional press," he says. "But I believe there's less harm is done in those cases where money changes hands, simply because the majority of these channels don't label themselves as journalists or critics," he says. "There is no pretence of authority or independence."

Bain points to quid pro quo relationships between websites and game publishers as an example of genuinely damaging practice within traditional game-focused press. "Preferential treatment from a publication is rewarded with preferential treatment from a game publisher," he says. "So you frequently see websites engage in pre-release hyping in return for, say, permission to review the game a day or two ahead of the competition. That arrangement is not becoming of journalists."

By contrast, Bain likens the role of many YouTubers to that of talk show hosts who might invite an actor or musician onto their programme to promote a product. "Nobody ever tells a talk show host that they're being disingenuous with these chats because impartiality was never the expectation." Moreover, Bain believes that long form video content makes it obvious to a viewer whether the game in question is as good as the presenter claims. "You can't lie about what's on screen," he says.

Channell believes that successful YouTubers have an arguably unique opportunity in contemporary media to distance themselves from all accusations of corruption. "Video game magazines and websites are, to some degree, always reliant on industry advertising money, which can stir up (usually imagined) corruption claims," he says. "On YouTube, Google will happily chuck an advert for chewable vitamins in front of your Minecraft video and pay you for the privilege. Because of its sheer scale, YouTube offers the potential for purity and sustainability. It's no wonder advertisers are attempting to dig their claws in as soon as possible."

***

While the fact that most YouTubers do not call themselves journalists arguably limits or reduces the harm of their unmarked paid-for coverage to consumers, they are also afforded fewer protections than traditional journalists. One young YouTuber who asked to remain anonymous said that he has seen colleagues who became popular for their coverage of EA's Battlefield series "dropped" by the publisher after they attended Activision's rival Call of Duty events.

There is an expectation of loyalty to one publisher's products, especially if those products were partly responsible for someone's initial success. If that loyalty is broken, there are consequences. As David Hepworth recently wrote in The Guardian on the dangers of advertorial: "Advertisers want to sleep with you but also want you to remain a virgin. They want to believe the favours they were granted are not being extended to the next hobbledehoy who comes along."

One anonymous PR said that his company has a specific plan for which YouTubers they bring out to events. There are the YouTube megastars such as Ali-A and Syndicate, a number of middle-tier presenters and, finally, a few smaller channels with fewer than 10,000 subscriptions. "The hope is that the little guys will make friends with the bigger guys and become popular," he said. "They will then always owe a huge debt to the company for helping to kick-start their YouTube careers."

Without a dividing wall between editorial and advertising, there is greater danger of coercion. It's an issue that all media publishers face as we enter an era where the majority of content is supported entirely by advertising (which, in turn, exerts greater power). The difference is that YouTube is too young to have known anything different.

Still, YouTube has rapidly moved from a breeding ground for talented young broadcasters who might never have had the chance to step in front of camera to a slick, commercial vehicle. The most prominent YouTubers are not only presenters, they are also powerful businessmen. The responsibility that comes with this power is simply to be truthful, lawful and open with their audience.

"Far too many YouTubers are dancing around the topic," says Bain. "They do the bare minimum to disclose the nature of these relationships or won't disclose at all. What's important is that it happens in the daylight and is not hidden away." Indeed, the solution to the problem is disarmingly straightforward. "People must be clearly notified when they are watching sponsored content," says Bain. "It's as simple as that."

Both EA and Activision declined to participate in this article. Ubisoft did supply an official statement. "YouTubers like other forms of media cover Ubisoft products as part of their own content programs and without incentives," it reads. "As commercial content producer we have on occasion also asked YouTubers to develop paid-for bespoke content - but have not contracted a specific opinion or sought to influence reviews. The YouTubers we work with only cover the products they are interested in and they value the opinions of their subscribers above everything else. We have not directly requested that any YouTuber hide the fact that he or she has been paid for content or that some component - eg travel - has been provided by us."