Wayward Manor review

Bump-mapping in the night.

Video games are well suited to explore cruelty. Inside their consequence-less bounds, we're able to persecute, wound and haunt virtual creatures, experiencing the illicit thrill of vindictiveness without the guilt chaser. We smirk as we send oblivious lemmings to their death over the cliff, or when a Pikmin catches fire and begins to skitter and shriek, or when the skater tumbles down the flight of stairs, landing legs akimbo.

In most cases, however, the virtual cruelty is informal, a by-product of our failing to perform the actions required of us by the game's designer. The horror inflicted on a game's characters is merely the collateral damage of our incompetence. Wayward Manor takes a different approach. Here the cruelty is formalised: you play as a ghost, working in cahoots with a grumpy 1920s Gothic manor as you work to drive inhabitants from the premises.

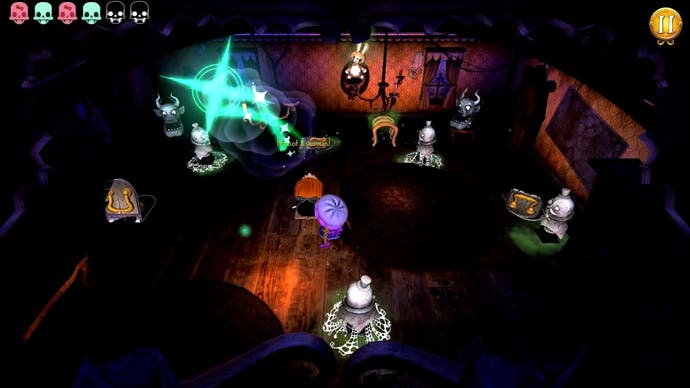

In each of the game's 25 stages you're presented with a top-down view of one of the manor's rooms. Your aim is to frighten any characters within the vicinity six times, thereby building up enough ambient fear to, finally, scoop up all of the room's loose objects into a bric-à-brac whirlwind and send the residents fleeing. You can't simply prod a person with a ghoulish finger, however. Rather, you can only interact with certain objects in the environment, each of which glows green. In this way you might cause a suit of armour to rattle, or a mouse to scuttle from cover, or a mounted tiger head to roar. These interactions will, if triggered at the appropriate moment, scare the nearest resident and earn you one of the six skulls you need to progress.

It's a game about angles and timing, largely. The mouse must cross the dithering maid's path at the correct moment to frighten her. The child must be sat next to the haunted painting else the ghost that swipes a cutlass from the canvas will have no effect. The bottle of poison must be dropped onto the butler's head at the precise moment he passes beneath the rafter. Later in the game you encounter characters that are able to fire projectiles, such as the twirl-moustachioed hunter, Theophilus Budd. He can be cajoled into firing off an arrow, which, if you correctly arrange the suits of armour in a room, can be deflected back toward him for a triumphant scare.

In each room there are more than six potential scares on offer, so you have a range of solutions to discover. In the main it's possible to work your way through each room in any chosen order - although once you pass certain thresholds new interactive options open up in a room (eg after three scares you might be given access to the window shutters, allowing you to invite a gust of air into the room which blows a trolley across the floorboards). As the game progresses there are some locations in which it's possible to snooker yourself by, for example, trapping a character in mousetraps (in which they flail, helpless and immovable) thereby forcing a restart on the entire room. With so many interlocking factors to the puzzles, it's no surprise that it's possible for a player to break a puzzle in such a way that a blunt restart is the only remaining option, but it's an unsatisfying feature of the design nonetheless.

Wayward Manor is a collaboration between the British author and scriptwriter Neil Gaiman and The Odd Gentleman, the Californian studio behind The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom. It's a suitable match: Gaiman's slightly overcooked prose ("These flittering pests are bastions of bad taste") fits well with the studio's whimsical art and sound design. These squat, neck-less characters are sound-tracked by a melancholic barbershop quartet which suits the writing (which itself complements rather than obscures the design). Gaiman communicates the vindictive nature of mansion, so eager to expel the 'scheming mites' from its rooms, and even succeeds in justifying the anger when the mansion talks of how poorly treated it's been by its residents.

But there is a roughness to the design, which nullifies some of this appeal. Puzzle solutions are repeated time and time again throughout the game, an obvious padding that perhaps speaks to a limited budget (even with the repetition the most ponderous player will finish the game within three hours). There's a sluggishness to the inputs - a significant problem in a game in which precise timing is key. Thanks to the occasional need to reset a level, you're never quite sure whether a particular failing is yours or not.

The designers encourage replay by way of 'secret scares', three per stage, which encourage you to scare the manor's inhabitants in specific ways or a particular order. But there's little incentive to find these solutions; indeed, there's no way to see which one's you've discovered and which ones you haven't once you've moved on from a stage's results screen. The information simply isn't recorded within the rudimentary menu system.

Despite these shortfalls, Wayward Manor has some spark and interest within its increasingly forsaken halls. It is, perhaps, an idea that couldn't sustain a full game - at least, not without Nintendo-style talent and timescales to allow the designs to fully blossom. Most players will be able to make it through the game through trial and error, carelessly clicking on objects to see what happens. But the game succeeds in making a thoughtful player feel smart enough to keep playing in order to what happens next. Neither a triumph of design nor storytelling and stymied by poor execution, Wayward Manor is a rough proposition. But there's something worthwhile here, even if it's the unusual power fantasy of being able to haunt an aristocratic family from the safety of the rafters.