P.T. is more than a teaser - it's a great game in its own right

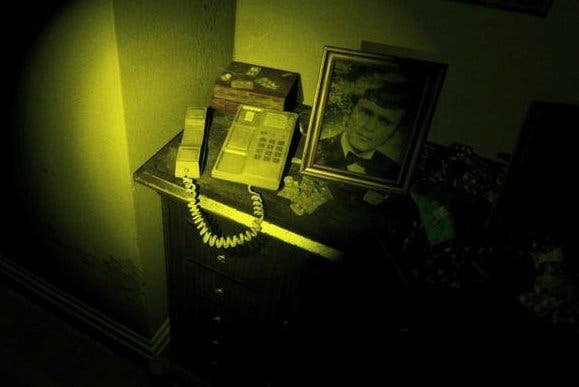

Hallway to hell.

"What's at stake?" someone once asked me when I explained my social anxiety about inadvertently saying the wrong thing to a stranger at a party.

"This person, who I will likely never see again, will go on in life thinking that I'm an asshole," I responded. "That shouldn't bother me, but it does."

Fear, as it turns out, isn't always a logical response.

This is especially the case with Kojima Productions' "interactive teaser" P.T. We all know by now that P.T. is a viral marketing project to announce Hideo Kojima and Guillermo del Toro's upcoming Silent Hill game, but its real surprise is how it manages to be possibly the scariest game I've played without relying on the usual tropes of horror game design.

Daringly, the entire game is set in one tiny L-shaped hallway with a minuscule bathroom hanging off to the side. Exit the corridor and you're booted back to its entrance. That's it. Worst case scenario, there's not much ground to retread.

Furthermore, I'm not sure if P.T. even has a fail state. I think I suffered a game over or two, but these might have been scripted parts of the story. Even after completing it I'm not sure if those so-called deaths actually happened to my character in their final timeline, or if they were untimely ends that were merely rewritten, the way game overs usually operate in our medium.

But that's the point, I reckon. It's never clear what, if anything, in P.T. is real. Welcome to Silent Hill(s).

That's part of what makes P.T. so fascinating. It doesn't matter what's real. Typically video games scare us by putting our progress at risk. Pluck away at Demon's Souls' Tower of Latria nightmare prison and your palms will sweat as you risk forfeiting your last 45 minutes of progress. That's a real consequence. That's danger. P.T.'s minuscule scale and generous autosave system ensures that you're putting nothing at risk. Shockingly, this doesn't ease the tension nearly as much as you might expect.

Instead of holding your progress hostage, P.T. relies on a much more old-fashioned method of horror: its sound effects, visual design, choreography, and difficult to decipher enemy placements. The peculiar lighting, the seemingly random placement of monsters that appear and disappear based on where you're looking, the deeply unnatural sounds of howling winds, baby cries, and radio static instil a profound feeling of dread, even though you know you're just sitting on a couch flicking a couple of analogue sticks with nothing to lose (besides your bowel control, as is Kojima's aim).

Kojima and company are almost supernaturally skilled in how it places players in a mindset where such low-risk terrors suddenly become the most important thing in the world..

That's because its claustrophobic, repetitive environment practically hypnotises you into a state of vulnerability. Escape the Room games tend to catch you off guard like that. Their cramped quarters suggest they should be easy to suss out with their solutions laying within spitting distance. Then, when you get stuck, you start going mildly insane as you're sure you've done everything. The beauty of P.T. is that sometimes you have. Sometimes the solution is as simple as walking forward, but you're so trained to believe that every cigarette butt or paper scrap could hold the key to getting out of this maddening space. Then, when you look at an object you've seen countless times before but this time something happens, it throws you off guard.

It's worth noting that P.T.'s puzzles, on their own, wouldn't be particularly memorable. Some are clever, some are overly obscure, and others are banal pixel hunts. But in a sense, it doesn't actually matter if they're that good. What matters is that they're deeply uncomfortable to deal with given the circumstances. They occupy your time, your attention, and give you reason to trot around maddeningly scrutinising every detail in the scenery. Stripped of the foreboding atmosphere, there'd be little of P.T. to recommend, but the puzzles don't exist in a vacuum and their frustrating nature blends effortlessly with the game's overall theme of cyclical mental anguish.

I'm reminded of a scene in P.T. (!) Anderson's The Master where a cult leader coaxes an impressionable, mentally challenged man into closing his eyes and walking back and forth for hours as he compares the feel of a glass window on his palms to the wooden wall across the way. After a while this sensory deprivation and repetition gets to the man until the window, the wall, and the ground beneath his feet become his entire world.

Viral campaigns are nothing new to marketing. We saw this sort of thing 13 years ago in the campaign for Steven Spielberg's sci-fi film A.I. But typically they're compiled of so much obscure information that they're not much fun on one's own and only take on a life of their own when tackled as a collaborative process. P.T. isn't like that (which probably explains why its great secret was cracked so quickly). It's feasible to solve on one's lonesome, but challenging enough that you'll probably resort to some sort of hints (confession: I did). Whether you solved P.T.'s mysteries on your own or with help isn't terribly important, however. As long as you at least put in a solid effort to unravel P.T. you're more than likely going to have a great, awful, terrifying, aggravating, and darkly comic experience.

P.T.'s biggest surprise isn't that Hideo Kojima is making a Silent Hill game. It's that it's one of the medium's most unique horror experiences in its own right.