Middle-Earth: Shadow of Mordor review

Wraith for life.

Despite a myriad of sources to draw from, few games have brought Tolkien's Middle-earth to life. There have been many attempts, from the ZX Spectrum text adventure The Hobbit to endless film tie-ins, but none have quite recreated the spectacle of steel sparking steel, nor the smell of blood and dirt and sweat-through leather in your nostrils as an orchestra swells triumphantly at your back and you charge valiantly towards almost certain destruction. Far from getting there and back again, most games set in Middle-earth fall before they've even left The Shire.

Middle-Earth: Shadow of Mordor, however, begins where most other Lord of the Rings games meet their end. When the Ranger Talion and his family are slaughtered by uruks under Sauron's command at the Black Gate, he is resurrected and his body bound to wander Mordor, the wretched region home to orcs and uruks where the very air, thick with ash and sulphur, chokes the life from lesser mortals. But not all who wander are lost. Now sharing a physical body with the Elvish Wraith Celebrimbor, and with naught but revenge on both their minds, Talion is set upon stirring trouble behind enemy lines.

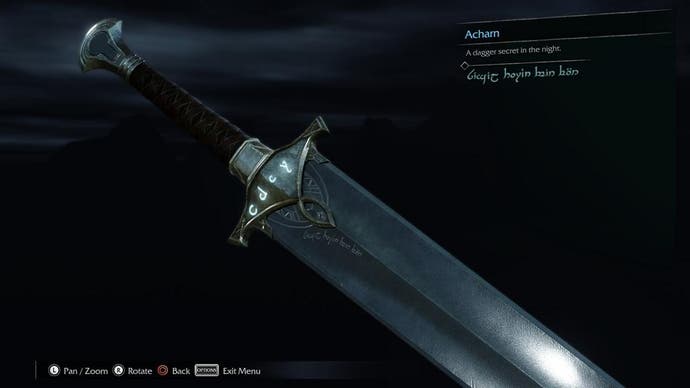

Initially, this means using a combination of stealth and melee combat to assassinate low-ranking Uruk captains within Sauron's swelling ranks. Talion can move swiftly and silently through Mordor, slipping his dagger into enemy backs unseen. Or he can stroll right up to his foes and face them head on, triggering the game's brutal rhythmic combat system, which combines Batman: Arkham-style striking and countering with racking up high enough kill combos to initiate instant executions and other special abilities.

As his power grows, Talion will unlock more wraith-like abilities which allow him to stun enemies, teleport to their location, or effortlessly pop their skulls between his palms. It's a subtle but effective instance of a skill tree reflecting a character's narrative arc; gradually, without even realising it, you're depending less on the noble path of the Gondorian Ranger and turning to the much more effective methods of terror and intimidation to get the job done - while relishing every moment of it.

Owing to the fact he's already done it once, Talion can't die. But that doesn't mean there aren't far-reaching consequences for him falling in battle. Time passes each time he does, and the orc that dispatched him will typically receive a promotion, causing the hierarchy of Sauron's local army to shift. As this goes on, orc captains will challenge one another for supremacy, and those that survive grow in power, advancing from nameless minion to elite captain to legendary warchief.

This all feeds into Shadow of Mordor's greatest accomplishment - the Nemesis system, a sort of procedural foe generator. Orcs and Uruks that you encounter on more than one occasion will remember you, often bearing the scars of having tussled with Talion before. They'll also call you out if they previously murdered you, or if you fled from a confrontation.

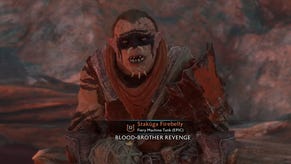

It's an exciting moment when an enemy shoulders his way to you in the midst of battle, seemingly returning from the dead just to go another round - only this time he's missing an ear or half his face. And whenever a high-level named foe enters the fray, he's accompanied by bloodthirsty Orcish chants of his name and a slow-motion camera zoom - an entrance worthy of any WWE star, and an effective psyche-out routine when you're already feeling overwhelmed and outnumbered.

But, after a while, their mangled faces all begin to roll into one - an orc is an orc is an orc, after all. It doesn't matter whether they're named Pushkrimp Bone-Licker, Skog the Grinder or Kargoth of the Irritable Bowel - their motivation is always the same and they're always replaced with newer and uglier usurpers faster as you can cut them down.

Where each foe differs, however, is in their strengths and weaknesses, which Talion can ascertain by squeezing snitches or gathering intel from other scattered sources. Some captains wield poisoned weapons, for example; others can call for aid, still others might have a mortal fear of fire, and some will just turn tail and flee if they feel a battle isn't going the way they had hoped. Once you whittle down a captain or Warchief's health enough, you can choose to execute them or allow them to live to fight another day. As your power grows, you'll gain access to the additional option of bending them to your will and turning them into sleeper agents, and this is where the full depth and complexity of the Nemesis system starts to show itself.

You can send a brainwashed captain to start a riot within the ranks, for example, or you can plant one as bodyguard to a Warchief on your hit list and direct them to stab him in the back when the time is right. The game consists of two distinct world maps, and throughout the first your aim is to simply kill off the five ruling warchiefs. The second, on the other hand, challenges you with the altogether more devious task of either forcing each figurehead under your influence or supplanting them with captains who are. Just like that, you become Mordor's very own master of puppets.

There's a lot of flexibility to enjoy here. You might decide that you'd rather just go for a warchief and all his supporters and followers head-on. And that's fine, but there's something much more satisfying about branding a captain, sending him off to engage in small territorial tussles whilst watching his back silently from the shadows, and then initiating a large-scale power struggle which, if successful, will mean his newly gained influence and followers are, by extension, yours to command.

There are times when the game's various systems get tangled up in one another. At one point I was undertaking a time-sensitive Weapon Legend quest from the back of a Caragor - Mordor's brutish, cat-like mounts - only to be clumsily interrupted by no less than three low-level orc captains I'd just happened to have passed by, who were queuing up to call me out. The Assassin's Creed-inspired parkour works well for the most part, but Talion can quite often find himself stuck in the scenery, while Caragors can be about as intuitive to control as a forklift over cobblestones.

The first couple of hours of the game, when inevitably you'll still be working out its quirks and dying relatively often, hold a little too much sway over how much you'll struggle later. Ultimately, my designated arch-nemesis Ishmoz Gold-Fang was an elite Uruk captain I'd met only once or twice; he'd simply gotten lucky and risen through the ranks quickly due to an unfortunate series of deaths I'd suffered on the other end of the map. And the three Black Captains - Sauron's might-made-flesh who temporarily replace the Nazgûl after their defeat by the White Council at Dol Guldur - are underdeveloped and laughably easy to defeat compared to their legions of bit-part underlings.

The game is set some time between The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and Middle-Earth lore has been handled well throughout. The story feels considered, brand new elements mesh well with established canon, collectibles offer nods to the likes of the Istari, Quendi, Dwarves and Bagginses, and there are even a couple of Tolkien's ubiquitous songs and verses snuck in between loading screens. Shadow of Mordor offers a deft and studious adaptation of the character of Celebrimbor, too, who is mentioned only briefly in The Lord of the Rings books but explained in more depth in The Silmarillion - as are the origins of Sauron, who we see in his 'fair guise' as the Vanyan Annatar during Celebrimbor's memories, which return to him throughout the campaign with the help of a tricksy Gollum. We also glimpse, in greater detail than ever before, the forging of the Rings of Power.

It's in this attention to detail that Shadow of Mordor reveals itself to be concerned with more than just lopping heads off overconfident orcs. Its open world doesn't always feel as big, busy or varied as you'd like it to - an understandable problem given that much of Mordor is a barren wasteland by definition - but you see Tolkien's uniting influence running through everything from the darkened slopes of Orodruin on the horizon to the skittering ungol underfoot.

One of the most enduring themes of Tolkien's universe has been the corrupting influence of power, but this has almost always been explored through the eyes of individuals that refuse to abuse that power. In death, Talion is free to do what those characters were never able to, and you experience first-hand what an intoxicating high that can be. At the start of the game you're not much more than a lowly Ranger, sneaking through camps and silently slitting Orcish throats in the night. By the end of the game you're boldly strolling through those same camps, as terrified uruks whisper tales of the Ranger-turned-Gravewalker over fortifying gulps of grog. There's plenty to see and do in Mordor when you're dead; all that's left, in the words of a wise old wandering wizard, is to decide what to do with the time that is given to you.