We cannot let this become gaming culture

Organised abuse and threats of mass murder: this is the legacy of GamerGate.

This week, feminist critic Anita Sarkeesian cancelled a university speaking engagement after threats that it would be met with a shooting spree. The news seems like a stark and spectacularly grim escalation of the mounting harassment of female game developers and commentators on the games industry.

In truth, as the Utah State University authorities noted, it isn't really an escalation at all. "After a careful assessment of the threat it has been determined it is similar to other threats that Sarkeesian has received in the past," the institution said in a statement. What seems like a new level of horror to outside observers has already become normality for Sarkeesian, the game developers Zoe Quinn and Brianna Wu, and many other women in games, not to mention in the tech industry and beyond. The difference this time is that word of it has reached the forefront of the mainstream media - including the New York Times' front page - damaging the public reputation of gaming in the process.

It's impossible to tell if the threats were serious statements of intent from a homicidal individual or were just made "for the lulz", in the language of online trolls, in order to sow chaos and discord and deny Sarkeesian a platform for her views. USU and the Utah police seem to think it was the latter. Does it matter? No, because both are attacks on free speech and personal liberty, and both are crimes.

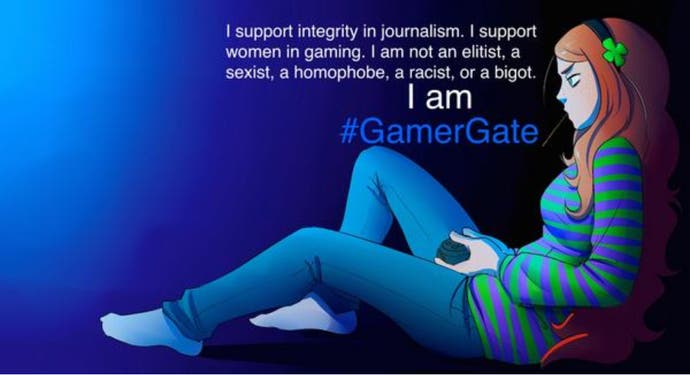

We also don't know if the individual or individuals who made the threats associate themselves with GamerGate, the online movement - for want of a better word - that claims to campaign for ethics in the games industry and has been engaged in a bitter war of words with the media over issues of diversity and cultural identity these past few months. (Sarkeesian said that one threat did mention GamerGate.) GamerGate does have proven links, on message boards like 4chan and 8chan, to the organised harassment of women online, but we don't know if its leaders - insofar as crowd-driven online collectives like this one have leaders - condone these latest threats. Does it matter?

Again, it does not. It cannot be in doubt that Sarkeesian has been targeted in this way because she has been one of the most prominent hate figures for supporters of GamerGate, who decry her Tropes vs Women in video games video series as a politically correct attack on their hobby. Instead of engaging with her arguments - which are certainly not beyond debate - Sarkeesian's opponents have opted for a rabble-rousing campaign of defamation, disinformation and organised harassment. It can be a surprise to nobody that this is where such campaigns end up, and more moderate supporters of GamerGate must accept responsibility for it. (And let us acknowledge for a moment the awful irony that, after decades of defending video games from accusations that they inspire school shootings, we now have a threatened school shooting explicitly inspired by games culture.)

This is not to say that some people who have aligned themselves with GamerGate don't have legitimate points of view. But at this stage, their association with it can only rob them of that legitimacy. What does GamerGate really stand for? It claims to oppose corruption in the games media. But its initial claims about Quinn's relationship with a journalist were debunked and since then, to our knowledge, it has not turned up a single credible example. All it has proved is that many people in the games press and business know each other, speak to each other and share similar views. The only persistent thread to GamerGate is vehement disagreement with those views - the views of the so-called "social justice warrior" - which hold that improved diversity and social representation in the games industry and in game content are necessary for the long-term health of video games as a medium.

At Eurogamer, we hold those views. We encourage debate, but we see no such thing arising from GamerGate. We condemn the deplorable harassment which threatens to chase a generation of women out of games and set the medium's movement towards a more progressive and inclusive future back by a decade. We believe the harassment is inextricably linked with the GamerGate campaign, which, through its continuing inability to articulate a reasoned position or engage in constructive dialogue, has now forfeited its right to be considered a true campaign, a true movement. It is no more than a front for trolling and abuse.

It has always been tempting, and to some extent true, to characterise GamerGate as the carefully amplified voice of a tiny minority. Perhaps these latest threats against Sarkeesian suggest a move toward even more marginalised extremism that will ultimately isolate and undermine the trolls. But we should be wary, because the current of legitimacy can flow the other way. Consider the story of tech blogger Kathy Sierra, who was hounded offline by a similar harassment campaign, only to later find one of her abusers, Andrew Aurenheimer, elevated to the status of a hacktivist folk hero of the tech community - after the New York Times had identified him as the author of a document defaming her and publishing her personal details online. We cannot allow anything similar to happen in games culture, and we urge everyone, whatever their views, to dissociate themselves from GamerGate and stamp out this abuse.

Strange as it may seem, there are positives to be drawn from this ugly situation. The first is that there is any progressiveness for the trolls to attack in the first place. Games are startlingly more varied and inclusive than they were when Eurogamer was founded 15 years ago. Progress is happening, it is fast, and it can only make games more interesting and exciting. As a generation of girls grow up playing Minecraft alongside their brothers, in a world where it's increasingly easy for anyone to make and distribute games, it is almost inevitable. This only makes the preservation of its forward momentum by stamping out harassment more important. Sexist abuse on the internet is hardly specific to games - this is part of a much wider problem - but there's no reason our community can't aspire to be one of the most tolerant online, rather than one of the least.

The second is this: games matter. This has historically been a medium of safe fantasy, of escape from the real world. In some ways, that is what many supporters of GamerGate seek to protect. But others, by expressing their feelings as threats, have paradoxically turned the discourse around games into one of genuine danger and political charge. We need to make the discourse safe again, but we probably can't reverse it back into apolitical irrelevance, and nor should we want to. Games reflect the real world and say things about it; these strange digital artefacts we all invest so much time in actually enrich, reveal and matter. Can that be a bad thing?

Finally, allow us to add a postscript which may seem inconsequential. Next to the suffering of the women targeted by harassment campaigns, it absolutely is. But then again, it's about language, and language is always important.

GG is now a common acronym for GamerGate. But it has another meaning in games culture: "good game", quickly typed at the end of a match of StarCraft or Counter-Strike or sent over Xbox Live after a close race in Forza; a sportsmanlike bow at the end of a duel, and always considered good form. Even within the heated world of online gaming, it's a universal expression of courtesy, of community spirit, of common enjoyment - which, it's worth remembering, have always been deeply held values of the gaming community.

Let's keep talking about how games matter, but let's turn our back on the term GamerGate and all the hate and exclusion it has come to stand for. We hope this is the last time we'll ever have to use it on this site. Let's have GG mean "good game" again.