If Early Access comes to consoles: Developers respond

Will commercially released unfinished games spoil consoles' picnic? We investigate.

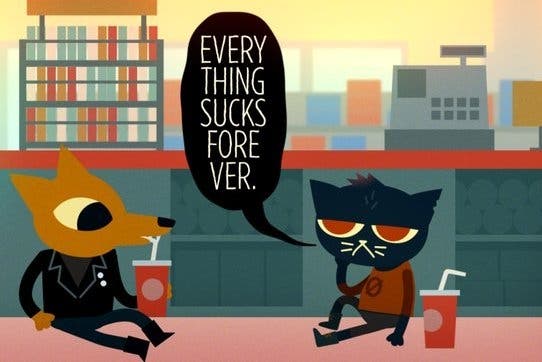

"This is an awful idea."

"No, no, no, no, no, no, NO!"

"I want a finished game not a buggy pile of garbage which detracts from the intended experience."

These were some of the responses we got to recent news stories about Sony and Microsoft considering adding an Early Access-like section to their brand of consoles.

It's an easy sentiment to understand. People were initially pretty gung-ho on Steam Early Access - where titles like DayZ and The Forest have enjoyed time at the top of Valve's distribution service's charts - but there's been some backlash to it as well. Having a game on Steam used to be a sign of quality. Now it occasionally lets duds like The WarZ and Earth: Year 2066 sneak past its borders on the basis of being a work-in-progress.

Console gamers have also been frustrated with the propensity of retail games releasing incomplete (Battlefield 4 being the best known example, where the publisher actually apologised for the sorry state is was shipped in). This wasn't the case a few years ago, so the idea of selling knowingly unfinished products could be viewed as the next step towards lowering quality assurance standards. Remember when we used to just put a game in a slot and hit "power"?

Worse, there are cases where in-development games are never completed. The Kickstarted Yogcast adventure comes to mind, as does the recent hullabaloo about Rust developer Facepunch Games greenlighting a new project before achieving a 1.0 "official" release of its popular game.

But will this mess of incomplete commercial content really soil the tried-and-true console experience? Microsoft said it's "something developers have been asking for," but do they only want it to con gullible users into handing over their hard earned cash, or would the new option help indie developers fine-tune their content before unveiling a finished product to the masses?

To figure out where developers stand on this hot button issue, we reached out to a handful of game developers to gain their perspective on the matter - and the consensus suggests many of them are keen on the opportunities an Early Access-like system would provide on console, with some reservations.

"Early Access can be a powerful way to let passionate gamers interact directly with developers and shape the games they love. Or, it can be abused as a way to throw out something half baked for a quick cash grab," says Jeff Strain, founder of State of Decay studio Undead Labs in a correspondence with Eurogamer. "We'd be strongly in favour of an Early Access program on console provided it was properly managed and used scrupulously."

"I think it's a wild new world, but the amount of tuning and early feedback could be amazing in helping to tune the game in mid to late development before a full release," adds Jake Kazdal, founder of Skulls of the Shogun and Galak-Z studio 17-Bit.

The Chinese Room (Dear Esther, Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs) founder Dan Pinchbeck is likewise a fan of this potential infrastructure. "There's no question for some studios it's a really important part of the financial model, and for those games, it's a really cool way of fans supporting the development of great projects that might not get made otherwise. And I do think it's an inherently better, more trustworthy, more sustainable model than Kickstarter, as you've actually got a fair bit of product there on the table before you commit."

Vlambeer (Luftrausers, Ridiculous Fishing) co-founder Rami Ismail is currently using Steam Early Access for its upcoming action roguelike Nuclear Throne and he's very much a proponent of this system. "We strongly believe that Early Access is not a pre-order or paid beta (or worse, alpha) program - it's a way for developers to get feedback on their ideas," he says.

"We feel it's tied to community interaction and incompatible with deep discounts. You build a small community of people that care about your game, you talk to them, figure out what they want from your game and improve your game along those lines if you want. We've bought into several Early Access programs, but a strong sign of community interaction and a stable game are baseline requirements for any interest from our side. If a company does it well, though, it can be an amazing way of being part of a games development."

Everyone we spoke to seems greatly in favour of the potential system, but does that mean they'd use it themselves? Not exactly, it turns out.

Different games would benefit from it differently, so while some could stand to playtest a title among several thousand people, others work best if they're unleashed at the same time to an entirely fresh audience.

Night in the Woods creators Scott Benson and Alex Holowka note that they're in favour of the Early Access concept, but have zero desire to put their upcoming coming-of-age tale on a service like that. "A game like Night in the Woods is the exact wrong fit for that. Our game has a story that is a core part of the experience, so playing through and then stopping back in a month to see if we've added better leaves or whatever makes zero sense," Benson explains.

"In our case it doesn't make much sense, as the game is meant to be played as one complete experience," Holowka adds.

Pinchbeck is likewise sceptical of how such a program would benefit his studio's upcoming exploration-based sci-fi story Everybody's Gone to the Rapture. "In some ways, I'm kind of happy it's not something we've had to do, as I think it's a really tough call creatively," he says. "I'm happier with the idea of ship it when it's finished, but I'm also aware that's got a lot to do with the types of games we make - Early Access just wouldn't work with them at all."

Kazdal, whose upcoming sci-fi shooter Galak-Z is an almost entirety mechanics-based action game, is far more drawn to this idea. "I would be very interested in getting dedicated analytics from players before we push the final game. It could be a huge benefit to the developers," he hypothesises.

Some of these developers have dealt with Early Access before and are adamant that it greatly improved their products.

Strain notes that State of Decay wouldn't be the game it is today if it weren't for Steam Early Access, which he claims was essential for developing the survival sim's PC interface. As such, the same service on a console would help developers effectively port their computer games to these other platforms.

"The real power of Early Access is that it can be a valuable feedback channel for the development team when a game is nearing completion, or after a game is released and you are shaping its future," Strain explains. "We have always believed very strongly in player feedback, and consider it to be one of the secrets of our success... So yes, we'd use Early Access on console to bring that player community into the development process, just as we do now on Steam for State of Decay."

Drunken Robot Pornography developer Dejobaan was among the first games on Steam Early Access and studio founder Ichiro Lambe found the process helpful, though he admits that taking in a ton of feedback can delay development even further.

"One downside of developing a game that way is that we've sometimes had to put it away for several months to get some perspective; and when we re-tool things from the ground up, there are folks who (again, rightfully) want to know where their finished game is," he says. "But it's worked for us in many ways, and it's worked for other games out there... If it were an option on any platform, we'd consider it again, but apply hard-learned lessons."

Even if Early Access feedback helps, one of the primary worries about it is that it will bring an influx of rubbish on to whatever platforms offer it, just as it has with Steam. While many games are wildly popular on there, there's a concern that Steam is getting flooded with too many less than desirable products lately.

Holowka suspects that this bout of new titles will only push developers harder to create even more exceptional products. "I think the 'flood' of new games is only going to get more intense," he says. "The indie scene is becoming more and more competitive. This is definitely good for the games themselves and for players. We developers have to stay on our toes and make sure our work is rising with the quality bar."

"The means of creating and distributing games are becoming more democratic," Benson adds. "Democratisation will always mean a great variety and that includes wide ranges of quality. But that's a good thing, not a bad thing (and also it's not like 'complete' games haven't always at times been buggy unfinished garbage). The games world is getting more complicated. We should welcome that with open arms."

Pinchbeck is more apprehensive on the matter, and ultimately finds that it's up to the consumer to research any products they're interested in buying before forking over their hard-earned cash. "I do share the concerns about Steam - it's very busy there now, and the combination of this with Early Access stuff, and Greenlight, always creates a risk that games which have a really cool elevator pitch or superficially interesting idea can get a lot of attention but ultimately fail to deliver, whilst other games get lost in that noise," he says. "A finished game is a hell of a lot more work than pitching a great idea for a game, and it's often the late polish to a title which makes it special, not the central idea, so I'm a bit cautious about it. In a way, little has changed: if you are considering buying a title, it's best to do your research, find the voices talking about it that you like and trust and not jump straight in and part with money on a promise or a cool looking pitch."

There's also a key difference between PC and console games: The latter is known for its simplicity, while the former is notorious for how malleable it is. PC gamers can rejig their kits, tinker around with such intricate settings as shaders and resolution, and even alter games completely by creating mods for them.

"People love consoles because stuff just works," says Kazdal. "PC gamers have a lot more patience for buggy games and challenging set ups."

Lambe suspects the reason console gamers are so suspicious of Early Access whereas PC players are okay with it comes down to one thing: familiarity. "Open alpha's been a thing on PC for a long time - think MMOs and ASCII roguelikes, some of which have been in development for decades. PC gamers are comfortable with it, because it's par for the course. It's something completely new to console gamers - there's lots of good in open alpha, but they're (rightfully) concerned that it'll bring some of the bad, too. I can't blame them," he says.

Pinchbeck also thinks it's a cultural mindset that's keeping gamers hesitant for in-development commercial releases to come to consoles. "There's a very different approach to games on the PC market, which has roots in things like modding, and the sense of underdog exclusivity that's a result of having been seen as second rate to consoles for a number of years in the global marketplace," he explains. "Consoles tend to be about finished products, or at least were until the Internet got to a point where patches could be a commonplace thing - whereas PC gaming was always tied to the Internet and a more active, fluid relationship between gamers and games was present. So there's a deep cultural divide, I guess, and that'll take some time to ebb away.

"Plus I think there's a sense that consoles are still the territory of big publishers, and they shouldn't need money to finish their games, whereas lots of smaller companies operate on PC. I understand the concern that smaller devs may suddenly find themselves competing for Early Access funds with larger organisations who can spend more upfront on making those Early Access titles feel like better value.

"I'm pretty optimistic about this stuff though. Gamers are smart, and they understand value and integrity. I think cynical Early Access programs will fail because people see through them, and where it's a good idea, it'll succeed. I don't know how realistic that is, but I'd prefer to be optimistic about it than cynical as much as I can be."