Everything not saved will be lost

What Destiny tells us about life, the universe, and everything.

Here are some recent thoughts of mine: I am playing too much Destiny. Also, games might be an expression of the futility of the human condition.

Two things are keeping me playing Destiny at this point, although they are really the same thing. The first is the most obvious - it is the grind. I'm chemically predisposed to respond compulsively to mechanisms which provide randomised rewards on the way to advancement along an arbitrary scale. Being aware of the ultimate futility of this doesn't blunt the compulsion for me (or indeed for my friends: an email I received this very morning from my Raid group - because that's a thing - reads: "Definitely up for getting this done - I need to increase the potency of my internet space man, guys, and that hasn't happened for a couple of days.")

The other reason I keep playing is that there's something I love about Destiny's fiction. I use the word fiction instead of story because it's fairly obvious at this point that Destiny doesn't have a story. So by fiction what I mean is the one-shot over-arching stuff - the restoration of mankind, and the reclamation of a future that is a recognisable extension of ours. This is the thing, really: that Destiny's science fiction is local, and its future seems reachable. These are our lunar modules on the moon, our spindly scaffold tech. We're nearly there. We will be.

What brings the things that are keeping me playing Destiny together - what makes farming ascendant shards somehow the same as admiring the cold ruins of a moon base - is one idea: progress.

I thought about Destiny and progress while I was watching Professor Brian Cox's new series, Human Universe, which is currently airing on BBC 2. The first episode charts humanity's journey from ape man to space man, and in it Cox is on the scene as a trio of cosmonauts return to Earth after six months on the International Space Station, their singed octagonal module - an object that has actually touched space - a dead ringer for those strewn around Destiny's moon. Cox explains that our ancestors from around 200,000 years ago had brains much like ours, so that if you could take one and give it a modern education "...there's no reason it couldn't achieve everything a modern child could achieve. It could even be an astronaut." (Or, I thought, a Guardian).

Of course the reason that early homo sapiens couldn't become astronauts is that everything we are and have achieved is built on the achievements of others. The defining mechanism of human development, of civilization, is language, and being able to store and pass on our accumulated knowledge through stories. Cox's beautiful phrase is that writing "freed the acquisition of knowledge from the limits of human memory", although a recent reddit showerthought post puts it almost as well: "School is meant to bring new humans up to speed on humanity's progress so far." It's a staggering, obvious-once-you-grasp it concept. tl;dr: Not starting from scratch every day is what makes us possible.

The first thing I thought when I heard this was: "What if dogs could do this?"

Then the second thing I thought was: "This is basically like checkpoints".

This is where we came in: with the idea that games might be an expression of the human condition. Or, more specifically, the idea that games - post-coin op games, shaped for the cosy couch market - are modelled on the almost-invisible-to-us course of human development. Destiny is a particularly good example because it's about humanity's entitlement to the stars - what British science-fiction author John Wyndham called "the Outward Urge" - but the actual game is about grinding and levelling, a hard-coded interpretation of the progress-through-checkpoints system that its wider fiction leans on. It fits both ways.

Look around, though, and it's obvious that other games, most games, work to this principle too. The Nintendo quit screen message "Everything not saved will be lost" has become a pop-philosophy meme: "We accidentally meant something!" But really it meant something all along, underlining the centrality of incremental advancement to video game structure. I recently replayed some of the original Resident Evil, and heard Cox's words on writing floating back to me as I saved my progress with a typewriter. Twenty years on most games don't even ask us to do our own saving, and instead have automatic checkpoints providing an unseen safety net against loss of time and status.

The system is so pervasive that exceptions become notable. Think about about how fraught and tender life seems in Spelunky, where death is death and the whole universe is at stake with each new exploration. Or even Dark Souls, which doesn't offer death so much as semi-mortal setbacks (setbacks which are not-insignificantly portrayed as a loss of "humanity"). It's obvious once they're missing that progress and checkpoints provide order to our experience of games, create a spine of meaning and orientation.

Of course you can run that sentence back and replace "games" with "life", or even "civilisation". Although it's funny that we should be on to meaning and orientation, because the other thing that Destiny makes me think about erases my sense of either. You see, the other thing that Destiny makes me think about is the unthinkable vastness of the universe, and the mathematical certainty that at some point humanity will be erased. And that, when this happens, our entire store of knowledge and experience - all of our checkpoints - will be wiped. Everything not saved will be lost.

Why does Destiny make me think this? Because it's about space, obviously, and every glance at the bottomless night sky should fill us all with terror. But specifically because it conjures a desperately optimistic vision of our future, in which - fair enough - a gang of alien races has achieved the galactic equivalent of smashing our head in with a car door, but at least they took the time to drop in. Currently, you will have noticed, mankind is the only documented form of intelligent life in the observable universe, despite our best guesses suggesting we really shouldn't be, given how big it is: we call it the "observable universe" because, despite the fact it's 13.8 billion years old, there are parts of it so far away that light from there hasn't had time to reach us yet. The truth Destiny's Hollywood conception of our place in creation conceals is that we are alone in an unimaginably huge nothingness.

There's an irony in that - that Destiny, a game about progress and reclamation, should be the thing to remind me of the vast blackness of reality. There is something about that vastness that makes me feel hopeless, whether we're alone in it or not. The scale deadens the sense of possibility and connection, that first step towards exchange and communication which is really the universal mode of checkpointing. We are so small, so far away, so intransigently brief, that the idea of us being seen and recorded by something else in the universe - uploading a checkpoint to a wider civilisation, or simply leaving behind a ghost save of all we are - is an impossibility.

It's really hard to concentrate on your k/d ratio when you're thinking stuff like this.

It's also really hard to finish a piece like this one. I have no final wisdom to impart - you will be shocked to learn that I have not solved the humbling enormity of existence. My reaction to these things is to look through the middle distance and sort of go, "Aworgh".

I did have an ending, one that ties things up neatly and sounds vaguely affirmative. I was going to mention the famous edit in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, the one that covers the entirety of mankind's evolution - from bone to spinning satellite - in a single dazzling cut. I would have said that, really, it hasn't been a jump cut but a grind, the ultimate grind, and that as a space-faring species we're barely out of the starting area. And then the final line would have been: "If games are an expression of the human condition, if the human condition is some kind of game, well - I wonder how far we'll get?"

But I don't believe that. It's too neat.

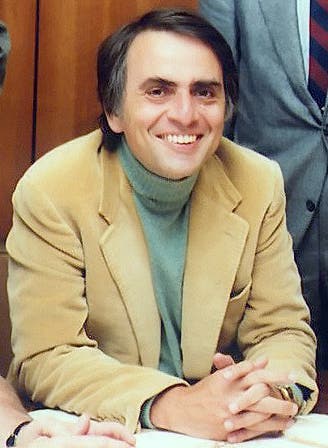

So I have another one, that's hopefully not so glib. I've always loved Carl Sagan's way of expressing the meaningfulness of consciousness, and the miracle that we're all made from atoms forged in collapsing stars: "We are a way for the cosmos to know itself," he said. There's an honesty to this - Sagan said it knowing our individual lives are preposterously short and, cosmically speaking, mankind's is not likely to last much longer. But there was for him a value in this temporary knowing.

So I'll end by saying that the value of games - these games that mirror the journey of mankind - and the reason to give over the precious, limited time we have to them, is this: that games are a way for us to know ourselves.

Seriously though - imagine if dogs could write stuff down! That would be hilarious.