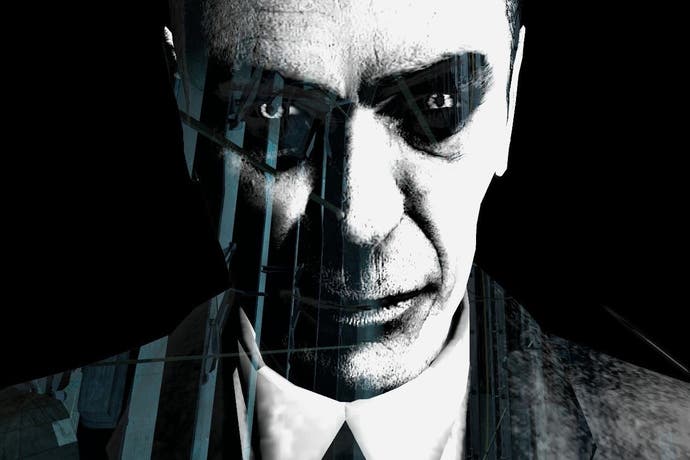

Half-Life 2: 10 years on

You remember, don't you, Mr Freeman?

Half-Life 2 has met the fate of all exceptional games. The 'classic' moniker almost instantly embalms them, gradually fossilising to a few forever-parroted talking points while the living entity is obscured. Physics, story, environmental design - Gravity Gun, City 17, Ravenholm. The game is shorn of context, too, and compared with successors that stripped its bones of ideas and sometimes improved on them. The keenly-felt absence of Half-Life 3 helps with this impression, but Half-Life 2 feels like a game on a tightrope - not stuck in the middle, exactly, so much as a pioneer of the modern first-person shooter that still contains much of the 'old' first-person shooter.

Half-Life 2's immediate competition was Doom 3, a comparison that's worth bearing in mind, because they're both linear corridor shooters designed to give the player a directed experience. When you enter a Doom 3 room and hit a button, monsters will pour out of the walls. When you see the trigger for a trap in Ravenholm, you know a zombie will soon appear near it. When you see rockets, you know you're going to fight a helicopter.

Let's not pick on Doom 3 too much, because it's fine for what it is, but this call-and-response design can be the bane of a linear game; if it becomes too predictable or repetitive, the player gets bored. The difference between Half-Life 2 and other linear shooters is how much effort has been put into its environments and pacing, how it peaks and troughs, and how much incidental stuff there is to find. id Software can make a gun go boom as well as anyone, but Valve give that squeeze of the trigger more context and impact than anyone.

Take as an example one sound effect, the Combine's voice-distorted chatter. One of Half-Life 2's staple enemies, the Combine soldiers are always accompanied by the sounds of their communications - they definitely seem to be speaking English, but you'd be hard-pressed to ever identify more than a word or two over the abrupt, whining rasps that texture it. Half-Life 2 uses music to establish mood, but the flood of Combine communication is a more subtle technique - flipping the player into the 'hunted' mindset, aurally discomforting and emphasising that in City 17, Freeman is the outsider. When you're 'deafened' by an explosion, the audio becomes a radio whine that parallels and loops back into the Combine's soundscape. As a piece of design, this gives the player practical information, disorients and intimidates, and also acts as a narrative beat for the soldiers' identity.

As this level of detail might suggest, the real key to Half-Life's narrative appeal is not that it has a good story. In fact, the 'story' of Half-Life 2 is a middle-entry, the second part of an arc that's yet to be concluded. One of main reasons folk are so impassioned about Half-Life 3's existence is surely because the current 'ending' is a cliffhanger (this should be called the Shenmue factor).

Half-Life 2's narrative strengths are in characters and individual environments, details, rather than the whole. To briefly digress: a monster cut from the original Half-Life was Mr Friendly, a bipedal grostesque that killed the player by grabbing and pulling them inexorably towards a large phallic protuberance - this was intended to play on the homophobia that Valve saw as rife among the game's target audience.

In Half-Life 2, the intended audience is older, the narrative tools are more subtle and the theme is now authority and control - suitable enough for the one free man. City 17 is a man-made environment that has been taken over by Combine technology, a parallel to the headcrabs in being a host kept alive by its parasite. There's something quite believable about a vision of the post-apocalypse where the vast mass of humanity accepts the new reality of alien control. This is why Dr. Breen is an amazing antagonist - he's convincing rather than maniacal, a politician talking about realism and hard decisions, commending humanity as he feeds her into the mincer.

The setting is one thing, in other words, while the atmosphere is another. In Half-Life 2: Raising the Bar, the long-out-of-print account of the game's making, there are several examples of short stories written for the benefit of the game's environment artists. These stories are not 'in' the game, but each area they take place in is designed to reflect their aftermath. There's no way for a player to piece together exactly what happened. Half-Life 2's strength is often mis-characterised as environmental narrative, when really it's the creation of environmental atmosphere - the suggestion of an unknown story, rather than the story itself.

Half-Life 2's pioneering use of physics is similarly praised and blamed from a slightly askew perspective. The implementation of Havok physics has obvious flaws - such as the crazy vibrating dance any object does as you carry it too close to things. The puzzles do a great job of wringing what they can from physics-enabled objects, but this is still a world with an enormous number of seesaws. That doesn't mean you get sick of them, exactly, but the mind is great at spotting patterns and not too long into Half-Life 2 your instant reaction to a blocked route is to look for something to weigh down.

The flipside is that Half-Life 2's core use of physics is not to be found here, but in the fun it creates with them. Being able to toss almost anything around and pile it up, in any given situation, is simply an enjoyable activity with no 'goal.' More obviously, the Gravity Gun is the greatest weapon or tool in any FPS ever: the opening hours train you to carry and stack, then this item lets you pull in almost any object and whack it across huge distances at speed.

The Gravity Gun encompasses multitudes of joys: the simple pleasure of pelting a giant box off a Combine soldier's head, the delicious risk/reward of hoovering in a red barrel and trying to fire it off before it explodes in your face, the childish joy in zapping a pile of wooden boxes to smithereens. The first thing Half-Life 2 does with the Gravity Gun, after seamlessly training you via a game of 'catch' with D0g, is to pack Freeman off to Ravenholm - a grim combat zone filled with zombies and sawblades. Don't tell me that's hackneyed, because it's an irresistible combination.

This is a fundamental characteristic of Half-Life 2: never mind the high-minded art direction and polish, this is first and foremost a great shooter. The general feel shows its age but Valve's minimalist style of gunplay still has realism and impact, and more importantly is used in a variety of ways that countless modern examples can't match. You're also vulnerable, capable of being taken down in one blast or swarmed easily by smaller enemies, a wonderful contrast to the sheer power and output of Freeman's arsenal. Everything works as it should, which means Half-Life 2's disparate elements have a great economy of use: exploding barrels, for example, are all well and good, but if you have an enemy that will grab and pull them up towards itself, that's another fun mechanic. If you get a Gravity Gun, there's another possibility.

This might sound like simple stuff, but it's why the heavily-scripted encounters work. Half-Life 2's guiding hand is omnipresent, which in lesser games leads to the player feeling like they're being manipulated. Humans are clever, so that impression never quite goes away, but it simply doesn't matter so much when a game's encounters are so well-paced and various as to lead you through its possibilities with minimal repetition. Valve is great at simple switches with big impact. Late in the game, you're stripped of your huge weapon set and forced to fight through a series of guerrilla battles with limited tools: a draining and tough series of fights. Immediately after this you get an upgraded Gravity Gun that can now blast things to kingdom come and are allowed to go nuts.

Audiences tend to think of pacing as an objective quality, and of course certain parts of it are, but the effect it creates is only ever subjective. One of my favourite parts in Half-Life 2 is also one of the most widely maligned: the long, languorous hover boat section. You've just spent two or three hours working through cramped corridors and dark alleyways, hemmed in on every side by barbed wire and fences with the cyber-SS in hot pursuit. Then you get a hover boat and shoot out onto a wide riverbed at speed, bashing through scattered foot soldiers, and it's a relief just to see the sky. After the brick-stacking puzzles and close-quarters combat comes the unabated joy of forward momentum. It feels like a great freedom.

The hover boat section is broken up by small puzzles, but the big challenge is a pursuing chopper that, eventually, you acquire the means to face head-on. This open arena battle is short, violent and brilliant, with a banging soundtrack and countless explosions ringing through your ears. Immediately afterwards you have to open the damn with Freeman to proceed, climbing off the hover boat to do so, and in this vast open space everything is suddenly quiet. You take a breath, think about the line between silence and desolation and move on - an amazing change of pace and atmosphere from start to finish, capped off with a flourish.

Half-Life 2's greatest triumph and biggest problem is imitation. Most FPS games then and now are a kind of hodgepodge of the best bits from other FPS games, in concept at least, and Half-Life 2's strengths have been kind of subsumed. Large parts of the design have been improved upon by subsequent titles which, while they may lack Half-Life 2's overall complexity, nevertheless manage to dull the original achievement.

Half-Life 2's shooting is pared-back, fast and frantic, and for that reason just about holds up, but it also feels anaemic next to the effects-laden feedback we expect from any FPS in 2014. The first-person platforming, of which there is a surprising amount, requires a finicky precision that has been all but focus-grouped out of the FPS. It is entirely understandable that someone in 2014 playing Half-Life 2 with fresh eyes might not take to the feel of it.

For this article I went back and reasoned that, if Half-Life 2 really was linear in anything but structure, then playing through again wouldn't be nearly as satisfying. But then there was a moment in Ravenholm when I got scared by a zombie, backed into a corner and triggered more enemies, then panicked forwards unloading a machine gun and hitting almost nothing. I retreated, feebly swatting at the headcrabs diving in, and crouched to make a smaller target. I noticed a handle and, surrounded by zombies, pulled it down to bring a stomach-level rotorblade whirring into life just above my head. Messy. And it was the first time I'd actually needed one of those traps, rather than planned for them.

Valve has, perhaps inevitably, moved its focus more towards multiplayer games and therefore player-directed experiences in recent times - with the Portal games the obvious exception. This is something of a pity, because Valve's history shows a quite brilliant understanding of single-player design, acutely sensitive to how players play games, and of the difference between a linear design and a linear experience. That's why Half-Life 2 was and remains a standout example of how to design a video game: it's not so much a linear FPS as it is an experience. Half-Life 2 always knows where you're going, in other words, but has plenty of room for unforeseen consequences.