The Smithsonian welcomes excavated E.T. cartridge

It belongs in a museum!

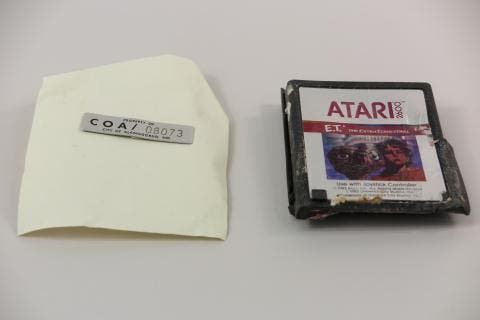

The Smithsonian has acquired one of the excavated Atari 2600 cartridges for E.T. the Extra Terrestrial.

While currently not on display, museum specialist Drew Robarge wrote about the acquisition and its importance in a new blog post addressing the unearthed Atari failure.

Robarge noted that video games are already well presented at the museum with the "Brown Box" prototype for the first video game console, a Pong cabinet and more, but there was nothing in the collection to signify the medium's crash in the early 80s.

"One big moment was unrepresented: the dark days of the 1980s when the U.S. video game industry crashed," Robarge said. "The Smithsonian is no hall of fame - it's our job to share the complicated technological, cultural, and social history of any innovation, including video games. That's why I was excited when we added a copy of the E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial Atari 2600 game to our collection."

You see, in 1982 Atari felt pressure coming from competitors Mattel and Coleco whose Intellivision and Colecovision consoles seemed poised to give the Atari 2600 a run for its money. So Atari pulled out the big guns: a licensed game based off the highly anticipated Steven Spielberg sci-fi parable about friendship, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Licensing the property was so expensive that Atari would need to sell four million copies just to break even. Worse, it only had five and a half weeks to make the game if it was going to achieve its vital Christmas deadline. As we all know now, it didn't sell anywhere close to four million units. In fact, many of the sold copies were returned by customers due to its obtuse rules and tedious design.

Naturally, this led to several truckloads of E.T. being buried in a New Mexico landfill, only to be unearthed earlier this year by production company Fuel Entertainment as part of the documentary, Atari: Game Over. The whole debacle led to a several-year crash in the industry that wasn't resuscitated until Nintendo and Sega came on to the scene in the late 80s.

Robarge never thought the Smithsonian would acquire an excavated E.T. cartridge due to the fact that Atari seemed pretty intent on keeping it buried. "Thinking that it would be forever buried in the desert if it was there, I put it down on my list to collect, but I knew that my chances of getting one were slim to none. If one did turn up for sale or was offered to us, how could I verify that it actually came from the landfill? Even if we could, we could not collect it as it was illegally removed from the landfill," Robarge recalled of his feelings towards the near mythical cartridges.

"It was to my surprise that one day I read that a company put in a proposal to dig up the landfill they believed containing the cartridges. Afraid that they might dig it up and just bury it all back in, I contacted Fuel Entertainment, the company behind the initiative, who offered to give us a cartridge if they found one. I waited for news of the results of their excavation to the public and, sure enough, myth became reality and they did find plenty of cartridges. True to their word, we received a cartridge and other objects relating to the excavation."

"The cartridge is one of the defining artifacts of the crash and of the era. In addition to the crash, the cartridge can tell many stories: the ongoing challenge of making a good film to a video game adaptation, the decline of Atari, the end of an era for video game manufacturing, and the video game cartridge life cycle. The cartridge also serves as closure for many things: the urban legend of the burial, the golden years of Atari, an era where American companies dominated the console scene. All of these possible interpretations make for a rich and complicated object. As they say, one man's trash is another man's treasure."