Games of 2014: Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor

Sweet and Sauron.

In the grand and miserable act of homogenisation that is open world game design in the early 2010s, Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor is as guilty a project as any Assassin's Creed or Far Cry. It presents an amalgam of now-frayed ideas lifted from its close (if thematically dissimilar) rivals. There are the equidistant towers, that staple of Ubisoft's greedy stable, which, once scaled, remove the fog of war from a portion of the map to reveal another psychically draining nest of side-quest markers. These vie for your attention, hoping to distract you from the game's core missions and thereby artificially bloat what would otherwise be a slighter game.

There's the overlaying task of hunter-gathering, in which you collect herbs and animal carcasses as you roam this sodden land (who knows how such a harvest can flourish under a sky of almost unanimous grey), either to create potions of varying usefulness, or to fill out a checklist of collectible items. There are the bases, which must be assailed, and the alarms therein which, when rung by an enterprising Uruk, summon fortifying reinforcements. There are the Caragors and Graugs, Mordor's take on Red Dead Redemption's wild horses, which can be tamed and ridden into battle or retreat. Then there are the moment-to-moment familiarities: the ability-unlocking levelling, the exploding barrels, the grisly stealth kills or, if you prefer a more direct approach, Batman's flitting, countering combat. Max Payne/ John Marsden's time-drawl special effect also makes it into a list of ingredients that should, by rights, create nothing more than a limp pastiche.

Even the literary source material, used to bring narrative context and sense is arguably fumbled. Rather than mimicking Tolkien's talent for coming-of-age stories (those quests that carry a young man from innocence to haggard triumph), protagonist Talion begins his journey in the fug of tragedy (his wife and child's murder provides the blunt justification for your one-man terror campaign) and ends his journey in the hollow aftermath of revenge, emerging unchanged by the experience. The racial subtext of Lord of the Rings has been oft debated. Shadow of Mordor reflects some of its substance. If this is not a game about ethnic warfare, then it can easily be seen as a game about class warfare (every Uruk was apparently born within the sound of the Bow Bells and could merrily moonlight in Fagin's gang). And if not class war, then Talion's good looks (a screen-pleasing meld of Aragorn and Jon Snow) and the Uruks' comical unattractiveness (the pinched faces, stretched ears and shark-bead eyes) make this at least a war on ugliness.

And yet, Shadow of Mordor emerges as the most accomplished open world game of the year, a game more technically proficient than Assassin's Creed Unity, less exhaustingly burdened than Far Cry 4 (although both games are equally repetitious) and more interesting than drab Watch Dogs and all the others. The interest comes not from the world itself, which is mostly a muddy, depressing field with dank offshoot caves on the periphery. Rather it comes from the celebrated social dynamic at the game's core, the so-called nemesis system, which brings a life and socio-political drama to the Uruk.

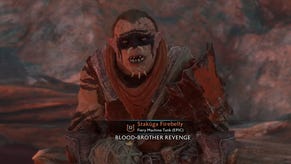

The design is straightforward: Uruks, like any army, are divided by rank. The smarter, more powerful or more experienced soldiers become officers; the newcomers act as grunts. As you disrupt Mordor with your dagger, sword and bow, so you disrupt the social ladder. A murdered captain makes room for a promotion, which, in turn, may create a power struggle. The game reveals the composition of the enemy's tiers and, in doing so, allows you to target specific enemies and create your own dynamic story, one that reflects the flexibility of live role-playing games more closely than most video game interpretations. The window into the rivalries and competition among the Uruk ranks also humanises your enemy. Then, as you gain intelligence about specific Uruk and read about their strengths, vulnerabilities and fears (be they of bees, of fire, of wild animals) you begin to view the opposition in more nuanced ways than Tolkien's fiction facilitated.

This is the game's strengthening pillar (one that regretfully, but perhaps fairly, will be oft-copied in coming years) but it's not the sole reason that the game is a success. In casting players as a phantom, developer Monolith Software is able to smooth out some of the physical friction. Talion is free to leap from the top of any cliff or tower and land anywhere without breaking bones (in Assassin's Creed you must always swallow dive into a trailer of hay). Arrows can be replenished from ghostly stocks stuck to any pillar or beam (no need to hunt about for a treasure chest). Moreover, regardless of whether this was due to time or design, the game shows certain restraint with its extra-curricular activities. There are trinkets to find dotted across the map, but it's a manageable and apropos haul, one that hopefully will not balloon in the inevitable sequel.

During the past few years we have learned the value of unpredictablity in games, be it the beautiful accidents of Minecraft's procedurally-generated vistas, Spelunky's unpredictable puzzles or XCOM's scattershot AI. Shadow of Mordor has a strict framework, but it houses chambers of pleasing unpredictability. Happy accidents result from this nest of systems. But you're sometimes also presented with an almost unassailable war chief, the product of a fortuitous roll of the dice who is, for example, immune to ranged and sneak attacks, who cannot be branded and controlled, who has inconsequential fears and insurmountable abilities and whose weapon "inflicts a lingering poison". Those players who run up against this kind of progress-blocking foe may be less enamoured with the nemesis system. But it's a reasonable risk to court in exchange for such dynamism and flexibility.

Was Shadow of Mordor overpraised for this invention (particularly when its designers borrowed so much else from elsewhere)? I think not. The nemesis system offers the first elegant solution to a problem that sits at the core of so-many blockbusters: how to bring the dynamism and flexibility (two of the medium's inimitable strengths) into the cinema-aping control freakery of modern big budget game making. The ways in which the game leads players to engage with the system (firstly by asking them to eliminate all war-chiefs, then by asking them to brand them) are ingenious. And the resulting memories endure. Shadow of Mordor is a game about revenge and despair. But on a systemic level, at least, it's also about hope and freedom.